By Jacob Morrow-Spitzer, Sid and Ruth Lapidus Graduate Fellow

The Day HIAS’ Ellis Island Agent Disappeared

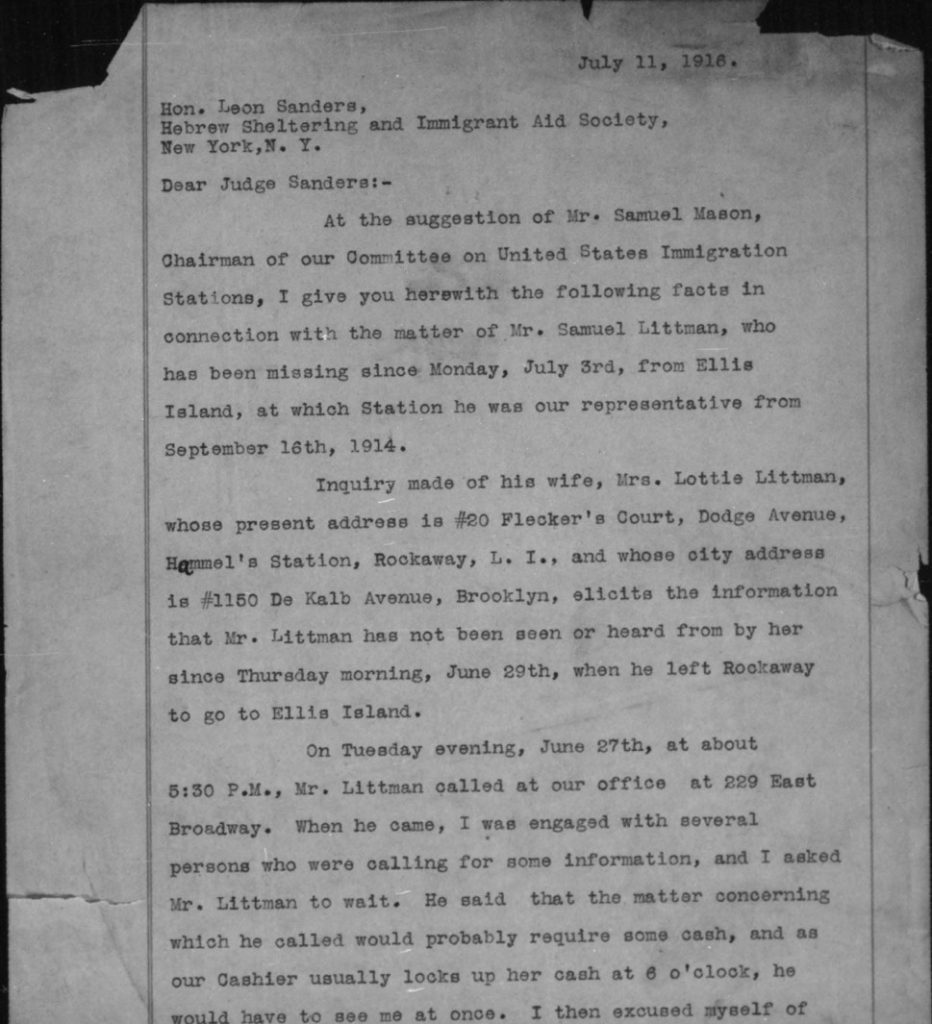

After twelve frantic days of searching for his missing colleague, a weary I. Irving Lipsitch sat down to write a detailed letter to his boss. “I give you herewith the following facts in connection with the matter of Mr. Samuel Littman,” he began, addressing Leon Sanders, president of the Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS). For the past three years, Littman had served as HIAS’s representative at Ellis Island, tirelessly assisting arriving immigrants and advocating for those facing deportation. But on June 29, 1916, he left his office early, reportedly to go swimming at Coney Island with his wife—and was never seen again. He vanished without a trace, taking with him thousands of dollars of borrowed money and signs of a deliberate effort to erase his trail.

By the time Lipsitch submitted his report on Samuel Littman’s disappearance to HIAS President Leon Sanders on July 11—a document now housed in the YIVO Institute archives—he had already conducted a thorough investigation. Lipsitch, HIAS’s general manager and former Ellis Island representative, noted that Littman had traveled to Washington, D.C. the day before he vanished. Littman had claimed the trip was urgent, aimed at meeting with Department of Labor officials to address deportation cases involving Jewish immigrants and other pressing matters concerning the Society.

Littman’s request to travel to Washington was not unusual. At the turn of the century, HIAS was one of three Jewish organizations—alongside the United Hebrew Charities and the National Council of Jewish Women—granted federal contracts to serve as intermediaries between immigrants and the U.S. government. When a deportation case appeared unjust, it was common practice for HIAS to petition federal officials in Washington to reverse the decision.

But this time was different. According to Lipsitch’s report, Littman had requested an unusually large cash payment from HIAS for his trip expenses. Before debarking to Washington, Littman then visited a diamond dealer in Brooklyn and borrowed a pair of $360 diamond earrings, which he promised he would return or purchase the following day. He also withdrew more than $700 in cash and obtained several money orders and loans from HIAS clients, bankers, insurance agents, friends, and family members. In total, Lipsitch estimated that Littman had acquired $2,369.40 over the previous few weeks.

I. Irving Lipsitch to Leon Sanders, “Correspondence of Samuel Littman and Irving Lipsitch, 1915-1916,” July 11, 1916. RG 245.2 Reel 10.24, File 130, HIAS Ellis Island Bureau. Collection of YIVO Archives.

After returning from Washington and briefly stopping at Ellis Island on June 29, Littman failed to report to work the next day. On July 1, his wife telephoned the HIAS office, asking if anyone had seen him—he had never returned home, let alone gone swimming with her, as he had told colleagues he planned to do. Despite growing concern, all attempts to reach him proved futile. A search party was dispatched to Coney Island, where a bathhouse owner reported finding Littman’s clothes, a ring, and $15 in cash. No one had seen him since.

Littman’s suspicious disappearance wasn’t his first brush with controversy. Three years earlier, he made headlines after being denied a promotion in the New York National Guard’s 47th Regiment, which he claimed was due to his Jewish identity. The fraternal organization Brith Abraham backed him, calling the denial antisemitic. The controversy gained traction in the press and eventually reached Governor William Sulzer—himself embroiled in his own impeachment scandal—who ordered a state investigation. The Attorney General substantiated Littman’s claim and removed the regiment’s commanding officer. (Governor Sulzer himself issued a strong public statement affirming that, “while he is Governor, the Jew shall have equal opportunities with other races.”)

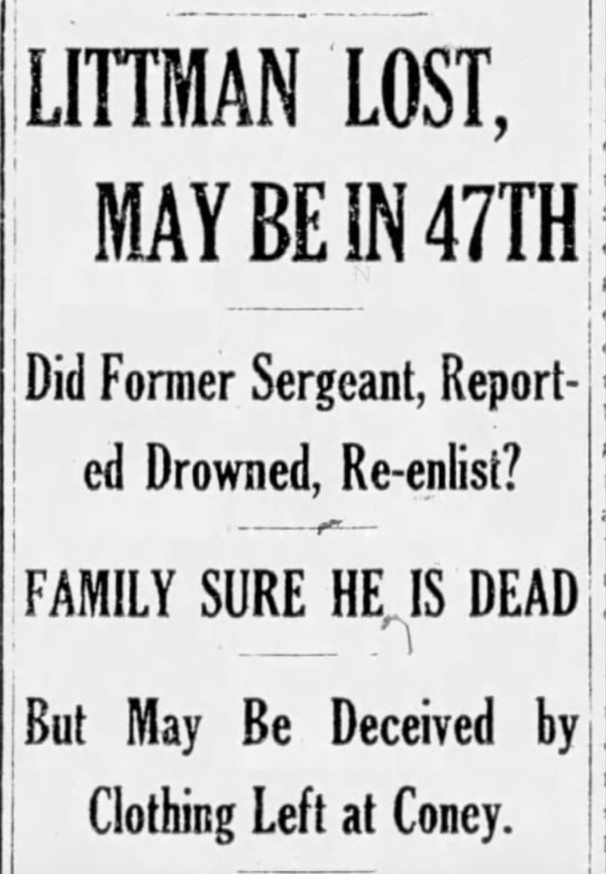

The scandal ended Littman’s hopes of becoming a National Guard lieutenant. In 1914, he shifted paths and became HIAS’s Ellis Island representative. Two years later, his name once again surfaced in the New York press—this time for his mysterious disappearance. Newspapers published sensational stories: some claimed he had started a new life far from New York; others believed he had actually drowned at Coney Island. But The New York Times offered a more plausible theory—that Littman had rejoined the National Guard under a false name. “Devoted always to the regiment he had left and fired with patriotism,” the Times wrote, Littman may have fled to join the Guard, which just weeks before had been sent to the Mexican border after being mobilized by Woodrow Wilson’s famous National Defense Act of 1916.

The Brooklyn Daily Times, July 5, 1916

In his report to HIAS president Leon Sanders, Lipsitch echoed the theory that Littman had absconded back into military service. He suggested that Littman had withdrawn hundreds of dollars in HIAS funds and, under the pretense of official business, traveled to Washington—possibly to enlist. Lipsitch speculated that Littman might have then gone to training camps in Peekskill or Beekman, New York, both active National Guard sites. Search orders were dispatched to those locations and to enlistment offices in Washington, but no trace of Littman was found. Ellis Island’s agent had vanished into thin air.

I. Irving Lipsitch to Leon Sanders, “Correspondence of Samuel Littman and Irving Lipsitch, 1915-1916,” July 11, 1916, Reel 10.24, File 130, HIAS Ellis Island Bureau (RG 245.2), YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York, 1.

Lipsitch to Sanders, “Correspondence of Samuel Littman and Irving Lipsitch, 1915-1916,” 1-3.

See Britt Tevis, “‘The Hebrews Are Appearing in Court in Great Numbers’: Toward a Reassessment of Early Twentieth-Century American Jewish Immigration History” American Jewish History 100 no. 3 (July 2016): 319-347.Lipsitch to Sanders, “Correspondence of Samuel Littman and Irving Lipsitch, 1915-1916,” 4-12.

Lipsitch to Sanders, “Correspondence of Samuel Littman and Irving Lipsitch, 1915-1916,” 4-5.

“Littman to Get a Hearing” Brooklyn Eagle, June 8, 1913; “Race No Bar to Guardsman” New York Times, March 17, 1913; “Colonel Resigns” Brooklyn Citizen, February 10, 1914; “Ex-Guardsman Missing” The New York Times, July 6, 1916.

“Samuel Littman Drowns at C.I.” Brooklyn Eagle, July 6, 1916; “Search Camp to End Bathhouse Mystery” New York Tribune, July 6, 1916; “Littman Lost, May Be in 47th The Brooklyn Daily Times, July 5, 1916; “Still Searching For Littman” The Brooklyn Daily Times, July 6, 1916.

“Ex-Guardsman Missing” The New York Times, July 6, 1916. The National Defense Act of 1916 federalized the National Guard. It was passed June 3, 1916, and troops were mobilized to the Mexican border on June 18.

Lipsitch to Sanders, “Correspondence of Samuel Littman and Irving Lipsitch, 1915-1916,” 5.