Marianne Rein. Click on images for larger views.

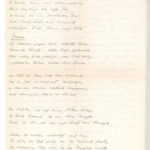

Images: Photographs of her in the 1930s; an illustration she did in one of her letters to Jacob Picard; a letter to Jacob Picard; a typed page of her poems; a letter from the National Council of Jewish Women; and a handwritten page of her poems—the second of which is translated below.

Europa

by Marianne Rein

The girls walked through the blooming landscape.

Following the most beautiful one — fast but smooth.

Not far away he glowed, white and mellow,

— scrunched blades of grass revealed his track —

the animal’s body with the withers,

with which it, almost gracefully, bent down,

so that, magnetized by his stature,

and innocent of knowing that he had outflanked her,

the beautiful girl swung on his back,

the nostrils crawling and steaming from his breath.

Meanwhile the animal arose, and snorted and stamped,

while the other girls were stagnant and afraid.

They did not see the god future generations believed in,

they only saw the bull that stole the virgin.

–

Marianne Rein was born in Genoa, Italy in 1911, to a German-Jewish family with roots in Wuerzburg. Her father died when she was only a few years old, and her mother brought Marianne back to Wuerzburg, where her family members were successful wine merchants.

Marianne grew up in Wuerzburg. She developed a great interest in writing and literature, and began writing herself. By the 1930s, her poetry and some of her prose pieces were being published in the Jewish press, especially in the Jewish Cultural Association’s journal Der Morgen. She wrote poems with subjects such as the beauty and course of nature, and classical mythology.

During this time, Marianne wrote to another writer who had successfully fled to the United States, Jacob Picard. The Leo Baeck Institute has a large body of correspondence, peppered with both handwritten and typed poetry, sent from her to Jacob Picard. It is how a number of her poems survived. Marianne lived with her mother in a situation that became increasingly difficult and frugal as Nazi restrictions tightened. Yet her letters to Jacob show her intense devotion to the nature of poetry and writing throughout this period. Jacob Picard attempted to help mother and daughter emigrate from Germany, but unsuccessfully. They tried many other possibilities as well, but in the end, escape was impossible.

Marianne went to work at the Jewish Nursing Home and stayed with her mother as they were forced into increasingly smaller living spaces under the Nazi laws. Many of her letters of this time are devoted to her search for a place of silence to write and explore her poetry. In October 1941, she wrote to Jacob:

“Today I have off, and I enjoy every minute of it. Oh, it’s a beautiful October day — Indian Summer. Otherwise there is a lot of work physically and mentally…..I feel an inner peace and balance, which is quite alien to me. Of course, the longing for silence never ends and I need several weeks in a completely different environment to live for what is my real job (writing). At present I have no time to think, let alone to let my growing consciousness be molded and formed…”

In November 1941, she was deported with her mother and 200 other Jews of Wuerzburg to the Riga Ghetto, where mother and daughter perished.

The legacy of Marianne Rein and her work would not have survived to the extent that it did were it not for the letters Marianne sent to Jacob in the last years of her life. A book was recently published of her work, and last year, performances of her poetry and writing took place in Wuerzburg, thanks to a recently formed active memory movement about the fate of the Jews of the city during the Holocaust.

“Europa” translated by Meike Bingemann; material submitted with notes by Michael Simonson, Leo Baeck Institute.