by Alyssa Carver, Project Archivist, Center for Jewish History

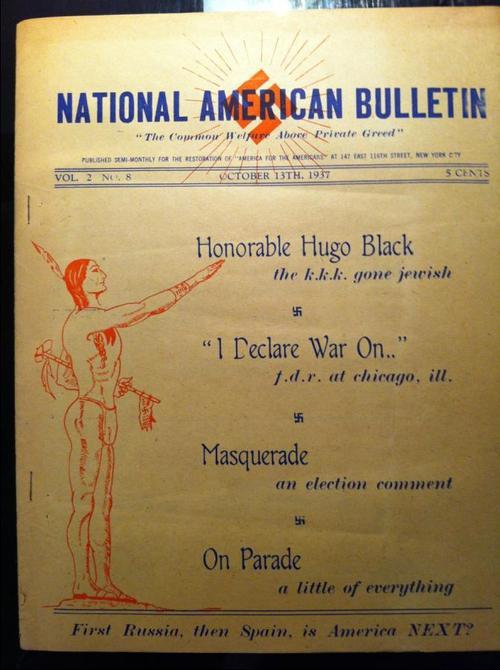

The Leo Baeck Institute’s newly processed Florence Mendheim Collection of Anti-Semitic Propaganda (AR 25441) contains a variety of American-made, pro-Nazi material from the 1930s, and even among such unpleasant company this publication stands out. On the cover of each issue of the National American Bulletin stands this figure: a muscular, loincloth-clad Native American performing the Nazi salute—complete with a tiny swastika flag on his tomahawk. Processing the collection, I had to pause to appreciate the innate wrongness of this image. And to wonder why a white supremacist group would choose an image of a non-white, indigenous person for a mascot. Even according to the warped logic of racism, this seems to illustrate an obvious logical fallacy.

On the other hand, the symbol of the swastika was already in use in cultures all over the world before Hitler appropriated it from the Vedic Indian tradition, and was in fact used by some Native American groups (see Wikipedia’s article on the history of the symbol). At the risk of affording members of the American National-Socialist Party (publisher of National American) far too much credit, maybe they already knew this? Nonetheless, it’s hard to believe that any Native American would in fact have endorsed the policies of the Third Reich. Then again, history is full of surprises—like Sufi Abdul Hamid, also known as “The Black Hitler of Harlem,“ another unexpected figure found in this collection.

Perhaps the American Nazis simply liked the proud tribal figure and didn’t consider the more grotesque implications of its use. Romanticized depictions of American Indians were wildly popular in European fiction, and even in Nazi Germany, Karl May’s western novels remained available while other books were burned.

It’s also worth noting that the phrase “Native American” didn’t exist yet in 1937, at least not as we understand it today. At the time, this term was claimed by white Anglo-Saxon Protestants of European descent who were born on American soil, like notorious anti-Semitic pamphleteer Robert Edward Edmondson, whose publications are found in the Mendheim Collection as well. His “Nativist” stance was hardly radical, however. Anti-immigrant movements already had a long history in the United States—strange as that may sound—as each new wave of immigration was met with an opposing wave of anti-Catholic, anti-Irish, or even (yes) anti-German backlash. In fact, the question of who is, or can be, or should be considered “a real American” continues to be a topic of heated debate today.

Although encountering material like the National American made processing this collection difficult at times, I am thoroughly convinced of the value of making it accessible for study. The continuing relevance of the questions raised by such artifacts indicates the importance of examining our notions of identity and nationhood in the full light of historical context, and of looking at the past with clear eyes.