President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the Jews: Part Two

by Ilana Rossoff, Reference Services Research Intern, Center for Jewish History

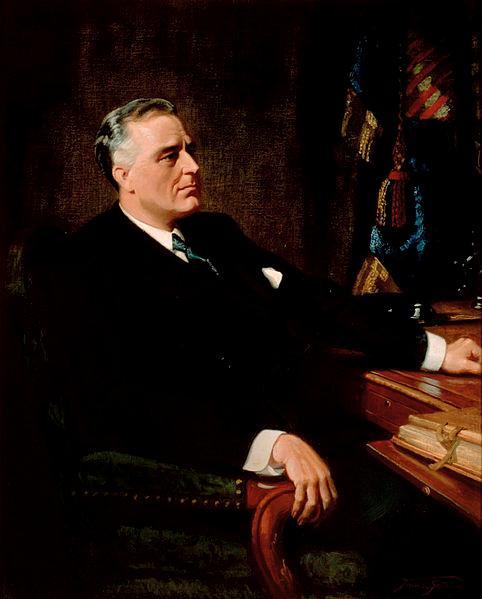

Official Presidential portrait of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 1947. by Frank O. Salisbury.

Continued from part one:

Refugees and Rescue: The Diaries and Papers of James G. McDonald, 1935-1945 (available here at the Center for Jewish History) brings to light the writings of James McDonald (the chair of the President’s Advisory Committee on Political Refugees, and also once the High Commissioner for Refugees from Germany under the League of Nations). McDonald’s papers include many exchanges with President FDR.

Contained in these papers are notes of FDR’s stated intentions to divide Jewish refugees between 8-10 countries around the world to maximize their escape; to press the State Department to increase the allowance of refugees; and to somewhat covertly secure funds for refugees. While the book does not reveal information about previously unknown efforts, it is seen as a record of FDR’s intentions to bring the U.S. to the forefront of refugee relief efforts during difficult political circumstances.

Despite these efforts, critics look at the deadly outcome of the war and point to areas of inaction to suggest that FDR’s efforts were insufficient given the dire circumstances.

There are two significant and symbolic incidents that critics of FDR often point to. One was when the S. S. St. Louis—which was a boat of Jewish refugees from Germany—arrived on the coast of Florida and was refused entry into the United States.

The second was a legislative effort to grant visas to 20,000 Jewish-German children refugees which failed because of domestic isolationism; FDR signed “File No Action” on an inquiry to the bill, which is often credited as the cause for the bill’s failure (though the order was not actually for the bill) (see Schlesinger, “Did FDR Betray the Jews?”). Ultimately, FDR is criticized for not doing more to override the intransigence of the isolationist (and allegedly anti-Semitic, in “the lower ranks”) State Department and have more visas issued, as well as for not pressing the international community to similarly take in more ambitious numbers of refugees.

In 1997, the Leo Baeck Institute, a partner organization of the Center for Jewish History, held a symposium at the Harvard Club in NYC on “FDR and the Holocaust: Did the President do all he could to save European Jewry?” Recorded in its “Occasional Paper No. 2,” the symposium debated issues of bureaucratic obstacles to immigration, popular sentiment in the U.S., the bombing of Auschwitz, the St. Louis ship as a symbol of inaction, and the extent to which FDR and others recognized the atrocities for what they were.

William vandan Heuvel (chairman of the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Institute) argued that the President was vehemently opposed to the Nazi regime since its rise to power, and that he waged a massive military campaign to stop it. However, this campaign was ultimately powerless in the face of legislative immigration restrictions that were “not the subject of an executive decree by the President,” and that still permitted a significant number of German Jews while refugees from other global conflicts—such as the Spanish Civil War or wars in South-East Asia—were given little allowance to seek refuge in the U.S. (See “FDR and the Holocaust,” p. 7.)

Henry Feingold (Professor Emeritus of the CUNY Graduate School and Center) argued that FDR did not fully appreciate the gravity of Auschwitz and other extermination camps because it was a “European affair” (read: not American), and that the U.S.’s involvement in the war was more in response to Japan’s attack on the U.S. than out of concern for the plight of those under Nazi control.

Arthur Schlesinger (Professor Emeritus of CUNY Graduate School) similarly pointed to the lack of understanding of what was truly happening—or rather, the disbelief that it could be happening—and to the lack of practical options for stopping it other than military bombardment, which FDR pursued.

Sidney Zion (columnist at the New York Daily Beast) gave the most damning report of FDR’s actions, arguing that Roosevelt could have summoned much more of his executive powers to force the State Department to increase visa acceptances, allow in the passengers of ships like the St. Louis, and could have been more publicly vocal earlier on to reveal the extent of the extermination campaign.

Many at the symposium (including questioners from the audience) expressed fond memories of FDR’s time in office. Some remembered how their families had benefited from either domestic policies or being able to seek refuge in the U.S. during the early years of the war. While most panelists agreed that it is highly unfortunately that more was not done to relieve the dire situation of Jewish refugees during the time of World War II, the debate remains open as to whether it was within the President’s powers to do so.

Given the generally accepted notion of the President’s sympathy, if not favor, for Jewish concerns, the debate seems to rest on how willing or able the President was to overcome the bureaucratic and political obstacles of the time. A further question in the broader debate remains: Had the United States sufficiently facilitated the reception of more European refugees in other countries, would this have affected the outcome, or changed the course, of the mass illegal refugee emigration to British-Mandate Palestine?

—–

Works Cited (in parts one and two of this article)

Cohen, Patricia. “Roosevelt and the Jews: A Debate Rekindled” The New York Times 30 April 2009: C25.

Dalin, David G. and Alfred J. Kolatch. The Presidents of the United States & the Jews. New York: Jonathan David Publishers, Inc, 2000

“FDR and the Holocaust: Did the President do all he could to save European Jewry?”, Leo Baeck Institute Occasional Paper No. 2. Symposium held at Harvard Club in New York City, May 1997.

Refugee and Rescue: The Diaries and Papers of James G. McDonald, 1935-1945. Ed. Richard Breitman, Barbara McDonald Stewart, and Severin Hochberg. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2009.

Schlesinger, Arthur. “Did Fdr Betray The Jews?” Newsweek Magazine 17 April 1994. (accessed 12 February 2013)

Wyman, David S. Paper Walls: America and the Refugee Crisis, 1938-1941. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1968.

Wyman, David S. The Abandonment of the Jews: America and the Holocaust, 1941-1945. 3rd Edition. New York: The New Press, 2007.

—–

To search the collections, click here.