We’re honoring National Preservation Week (April 26 through May 3) with a series of posts from our archival experts about the best way to take care of your precious artifacts at home.

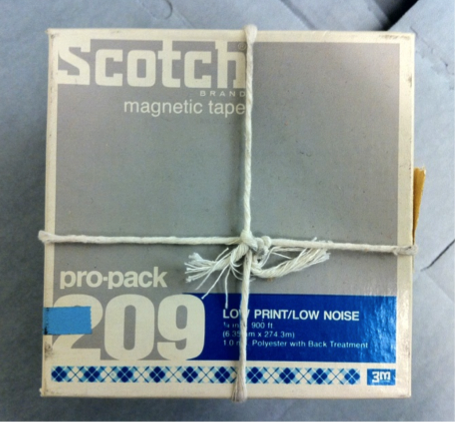

Above: An unprocessed AV collection.

by Alyssa Carver, Processing Archivist, Center for Jewish History

Archivists work hard every day to preserve the historic record, but our main concern is with providing access to the information itself. This means it is necessary to care for the objects and artifacts that convey information, but we can rely on specialists like our conservator Felicity Corkill to provide guidance on complex material issues. In contrast, an archivist might describe “preservation” as an intellectual task, one that involves preserving authenticity, context and meaning.

To do so, we must create order out of chaos—at least, we try to. The reason we maintain archival collections is so they can be used for research, but how do potential researchers know what we have and whether it’s relevant to their interests? Well, we arrange the collections (for example, by date, creator or function) to help identify what they are about, and we describe them with online catalog records, finding aids or collection guides that are available to the public.

Here in the Shelby White & Leon Levy Archival Processing Laboratory, the bulk of our collections are comprised of paper documents: letters, reports, certificates, legal forms, manuscripts, newspaper clippings, scrapbooks, posters, photos—an astounding variety, really, once you start to enumerate the types.

Something all these items have in common, besides being two-dimensional and thus fitting within flat folders and file boxes, is that we don’t require any special device to learn their content. Yes, we might find ourselves puzzling over a bit of difficult handwriting or having to solve the small mystery of some undated correspondence…but audiovisual (AV) media provide a whole new set of challenges. A videotape, film reel or audiocassette doesn’t “tell” you anything unless you interact with it through some kind of technology.

This creates a number of difficulties. Sometimes the format is obsolete and the required playback technology no longer exists, or is prohibitively expensive. Playback also shortens the “life expectancy” of these types of media—quite the opposite of our goal of preservation! Perhaps the biggest problem, however, is the time it would take to interact with every individual AV item. With paper, we can generally glance at a name or date and make a decision about what the item is. Depending on the nature of the collections, archivists at the Center process an average of several file boxes per week.

For libraries and archives that specialize in AV media, it makes sense to invest in the equipment and the staff time, but it would be terribly inefficient for us here. Of course, we provide the proper housing and environment for these items to last as long as possible, but this doesn’t fulfill the most important part of our job: to provide access through description. What this means is that the information associated with the media becomes very important—the labels, the packaging, the dates of nearby items.

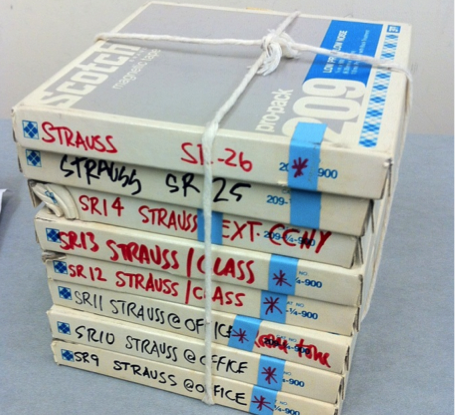

The creator of the collection pictured in the image at the top of this post provided labels for most of the tapes, including dates, names or locations. There are a few ways in which she could have been more consistent, but having even this much information makes a world of difference. It’s those details that make this an “archival collection” instead of a box of random tapes you might find at the flea market. As you can see from the examples below, it’s considerably less daunting to survey a neat stack of labeled tapes than a mysterious container of media.

Above: Unidentified AV material—a challenge.

Above: Labeled AV items—a great help!

Some things you can do at home to help your future archivist? Besides proper storage of AV media, get those items labeled—and don’t wait until you’ve forgotten the important names, dates, places, occasions and purposes. Find ways to keep track of and maintain all of this information (also known as “metadata”), and you might find you enjoy remembering your own personal history—and knowing precisely where those memories are stored.

More posts in our National Preservation Week series:

Your Digital Family Album: A System for Safekeeping

For Delicate Books, Safe and Snug Houses

Defending Precious Artifacts from Mold and More

Organizing Digital Files: Getting Your Photos and Scans in Shape