By Dong Eun Kim, Head Conservator, Center for Jewish History

Post 2

In the previous blog post, the Werner J. and Gisella Levi

Cahnman Conservation Laboratory had received the Leo Baeck

Institute’s Metz Jewish Community Collection for assessment and treatment. The

Conservators in the lab were captivated by these artifacts; we felt there was

something truly important about them, yet none of us could identify what it was

that made them feel so special.

Before finding the answers, we were

about to embark on a journey of fascinating dead ends. Our investigation

begins with a condition report, an assessment of the state of the artifact. We

identified Iron Gall Ink in the intermediate stage of oxidation. In some cases

large deposits had faded through to the verso (back), and in others it had deteriorated and degraded the paper, causing cracks and

losses due to corrosion.

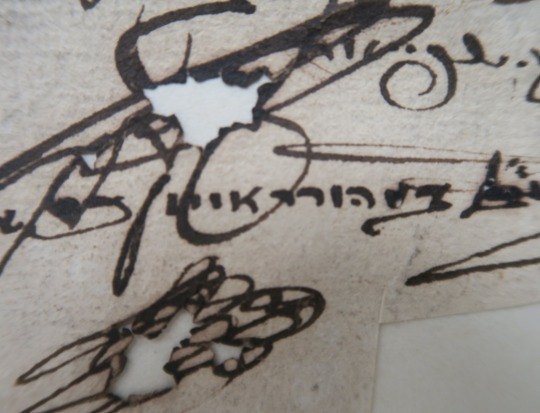

Detail photograph

showing loss of paper (top) and crack (bottom) due to ink corrosion, Leo Baeck

Institute ArchivesPhoto credit: Dong Eun Kim

Treating this requires meticulous

examination, using light tables and even microscopes to identify problem areas.

This inspection exposed a compelling new detail: in several places, the ink

seemed to have a gold sparkle to it, almost like glitter. Magnification and UV (ultraviolet) fluorescent light revealed colored particles, like grains of sand. The material

appeared throughout several of the manuscripts.

We were delighted and intrigued by this new detail, and

began appropriate analysis to understand what we were seeing.

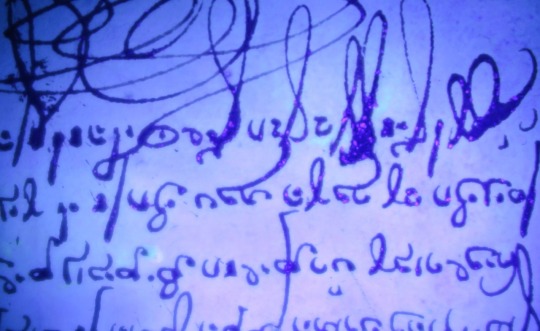

Detail photograph showing sparkling

letters photographed under visible light, Leo Baeck Institute ArchivesPhoto credit: Dong Eun

Kim

Detail photograph

showing glittered letter photographed under UV light, Leo Baeck Institute

ArchivesPhoto credit:

Dong Eun Kim

Detail photograph

showing “blotting sand” under high magnification, Leo Baeck Institute ArchivesPhoto credit: Dong Eun Kim

Research revealed the gold particles as “blotting

sand,” a substance “applied to wet ink for centuries with the intention of

speeding up the drying time of writing inks. Blotting sand consists of small

particles of a variety of materials (minerals, bio-minerals, glass, metal and

others).” (Reference: Reissland et al. 2006, Milke et al. 2003)

A remarkable find, but entirely common in documents from the

time period. Necessary information for effective treatment, yes, but we are no

closer to understanding why these objects feel so intriguing. We press on…if

not the ink, perhaps the paper it’s printed on?

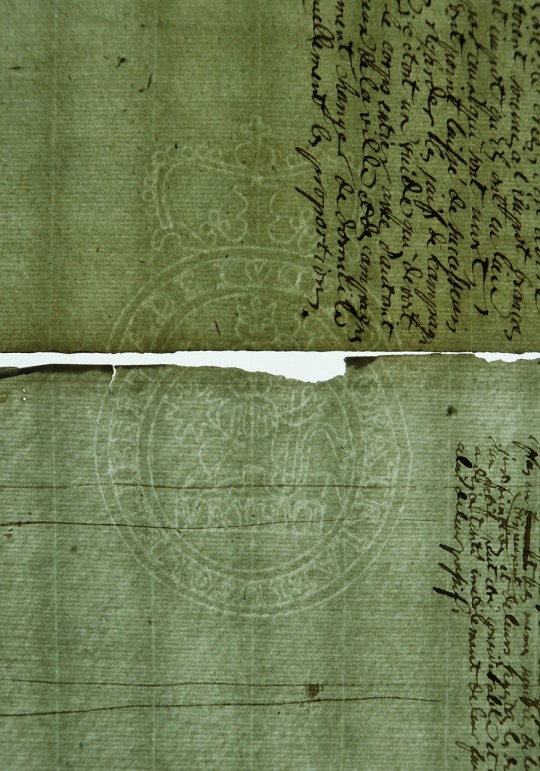

Careful examination

of one of the documents revealed a watermark, which often helps in identifying

historical elements. This gave us a new avenue of research, offering new hope

of discovering the importance of the artifact.

Paper watermarks are

the designs left in the paper from the structure of the paper mold. Wire

threads are sewn onto the mold wire cover, producing thick or thin sections of

the paper during its manufacture, and forming an image that can be seen when

holding the paper up to a light source or in raking light.

Due to

heavy writing on the page, the watermark was very difficult to identify. By

combining two pages with partial watermarks, we were able to get a sense of the

whole. The

design includes an inscription circle topped by a crown, which surrounds a lion

and plinth; it appears to contain a phrase beginning with the words ‘pro

patria’, which is similar to those found in Dutch and English papers in the

18th century. It is about 4

inches wide and shows the lion carrying a corn sheaf and a spear, standing on a

plinth with the letters ‘VRYHYT’.

Detail photograph

showing watermark under transmitted light, Leo Baeck Institute ArchivesPhoto credit:

Dong Eun Kim

Because versions of this

watermark were commonly used by Dutch and English paper makers, they may have

been from one of a dozen different paper mills. The missing “E” on the plinth

likely indicates a lesser known manufacturer, which leaves us without enough

data to reach a conclusion about the paper’s origin.

However, handmade paper was

made on a mold that had chain wires laced or sewn directly onto the wooden ribs

of the mold. This caused the pulp to lie heavier along each side of every chain

line. European paper made before 1800 may often be distinguished by this

peculiarity. One of the methods used in paper analysis is the measurement of

these features, and the measurement distance between chain lines in this case confirmed

that this paper was Dutch and not English.

As rewarding as it felt to

have identified the country of origin for the paper, it offered no new answers.

Dutch-made paper in the 1700’s was quite common all over Europe and even abroad

– even the original draft of the Declaration of Independence was written on

Dutch paper.

Why are we still so compelled

by these objects?! Frustrated but undaunted, we persevere…