By J.D. Arden, Reference Services Librarian, Genealogy Specialist, Center for Jewish History

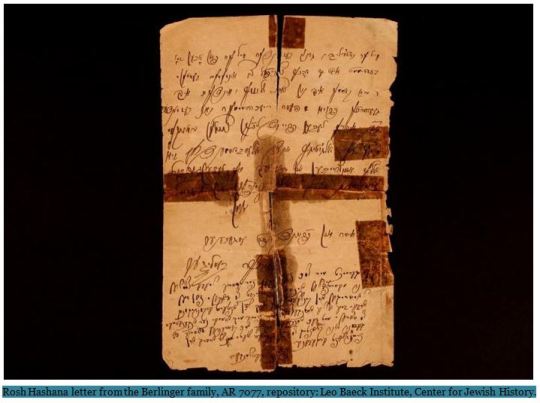

Here at the

Center for Jewish History in the Ackman and Ziff Family

Genealogy Institute, researchers in genealogy often

discover or bring in old postcards, letters, manuscripts or vital statistics

records. These old documents are notoriously difficult to read! Some are in

Yiddish, some in Hebrew. Here are my tips for deciphering Hebrew-alphabet

penmanship and my suggestions of tricky handwriting patterns to watch out for.

Tip 1. Don’t just struggle on the word or name you need to decipher. Look at the entire writing sample for context and orthography patterns.

If you find another recognizable word, use that to build a key of how the

author writes certain letters.

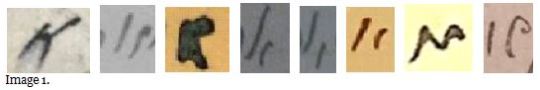

There are many different ways to write an alef – א,

the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet, for instance. Here are a

few:

Tip 2. Trace the writing yourself with your finger, reading aloud. A

difficult word may become clearer from the context of the document and through

the action of re-tracing a jumble of letters.

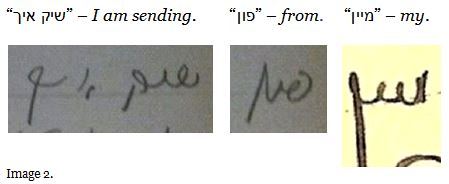

Unlike

in Modern Israeli Hebrew, handwriting in

Diaspora or antiquated Hebrew, Yiddish (or other

Diaspora Jewish languages in the Hebrew alphabet) often uses fanciful ligatures

and final flourishes. Intermediary

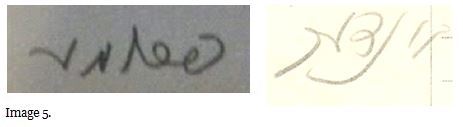

letters, especially yud and double yud, can be absorbed into one or two

wavy lines, see some examples in Yiddish below:

The vertical lines of vav, alef, and yud can become

almost indistinguishable, here in Yiddish “וואס שרייבסט דאס” – which you write that.

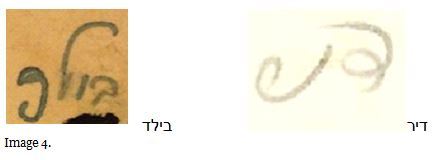

Here a flourished hooked daled ends the word

“בילד” – photo and a

final resh is often reduced to a horizontal flourish, as in the sample “דיר”

– [to] you.

This phenomenon of a how a print standard of writing evolved into

certain patterns of cursive script can be observed in the many connections between

the Hebrew alphabet and the modern Arabic alphabet, which now functions as a

cursive script but is still related to earlier writing systems.

Here,

in the name (or adjective) “פרומע” – Fruma (pious), and

the word “קינדער” – children.

Tip 3. Take into account that, before the modern convenience of ballpoint

pens, pen and ink was messy! Letters might be smudged. And before the era of

spell check, spelling might vary widely depending on regional dialect or the literacy

of the author. Here are some common issues related to the nature of ink on

paper and to non-standardized spelling.

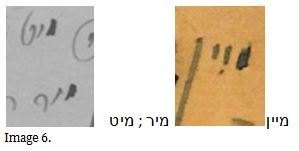

The letter mem is often reduced to what appears as one thick mark,

here

“מיט",

“מיר” and “מיין” with, me and my.

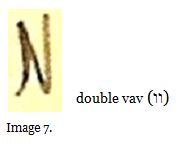

In contrast, a double vav with a

connecting diagonal can often look like a version of a standard handwritten mem.

Like in Modern Israeli Hebrew, the relative size of the similar letters

yud, vav, and final nun (י.ו.ן) can vary from sample to sample.

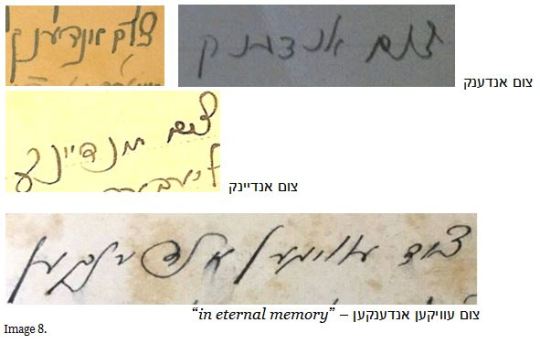

The most common phrase accompanying a postcard or photograph

is “in [the] memory of…” – צום אנדענק פון. Here are several samples to compare: in some dialects of

Yiddish, ע becomes יי and, פון becomes פין.

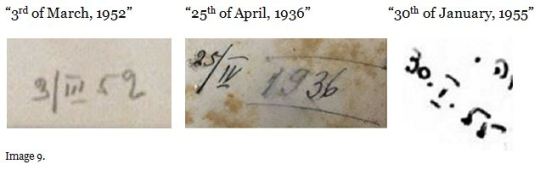

Tip 4. Remember to think in historical context. Conventions of another era

and country may be unusual at first – like how to read a date.

Dates in old letters and postcards can often in the format

of: day in Arabic numerals / month in Roman numerals | the abbreviated decade

of the year in Arabic numerals; see below:

Sometimes letter-writers whose non-Jewish majority language

education or experience was in Polish, Russian, or another European language,

will habitually follow the convention of adding the abbreviation “year”: r (rok),

г (год or година), etc. to the end of the date in Arabic numerals – even if the

text of the letter is otherwise completely in Yiddish or Hebrew. Sometimes an

author might mix the Hebrew word “year” – שנ with Arabic numerals.

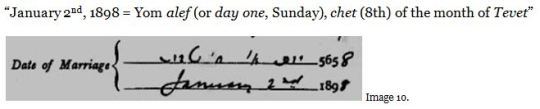

It is worth noting that Jewish dates, years, enumeration,

lists of 1-2-3, all can be expressed only through letters of the alphabet –

each Hebrew letter having a numerical value. In the context of Jewish-language

manuscripts or printing, there is no necessity for the use of a numeral system,

Roman or Arabic. The Hebrew alphabet as numerical equivalents is most often

encountered in genealogy research of tombstones, marriage ketubbot, and in

personal correspondence. Letters used as a numerical equivalent are marked with

a geresh – a slanted apostrophe-like sign used in the Hebrew alphabet as

a diacritical or punctuation mark. Often in a religious or antiquated writing

context, the geresh equivalent that is used is the more scriptural

symbol tsinnorit – similar to a sideways S and often simplified as a

horizontal line. Numerical equivalents and all Hebrew abbreviations are marked

with a geresh (or gershayim, plural).

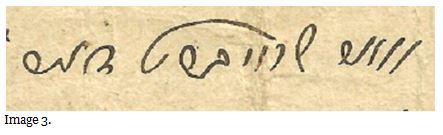

Below is an example of a Hebrew date sequence with numerical

equivalents represented by letters marked with a geresh:

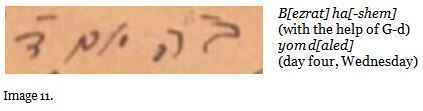

Here, a conventional religious abbreviation and a weekday

indicator are both marked with the tsinnorit above the letter instead of

a geresh:

And lastly, Tip 5. Take a break and ask a friend to

take a look. Sometimes a deep breath and a fresh pair of eyes will help crack

the case!

For

further exploration of other styles of handwritten Jewish Diaspora languages

among many communities and some specific to the Sephardi and Mizrachi Diaspora,

check out this link to a University of Washington Jewish Studies video – Learn

How to Write Soletreo (the Ladino Alphabet) with David Bunis.

The library and archive online catalog

of CJH can be searched in Roman or Hebrew script, and our catalog results page

can be refined to material in many languages, including Jewish Diaspora

languages such as Yiddish, Ladino, Judeo-Arabic, Classical Syriac,

Judeo-Persian, and Samaritan Aramaic. Information pertaining to many other

Jewish Diaspora languages (Judeo-Tat, Judeo-Provencal, Haketia, and others) can

also be found within our collections.

For more information about our vital statistics microfilm

collection, our Genealogy Institute Membership Program,

workshops and research guides, please visit www.genealogy.cjh.org

Note:

all numbered images are excerpts, used for the sole purpose of this educational

article, from the public social media pages Facebook Genealogy Translations and

Facebook Tracing the Tribe.

Thank you so much for this wonderful essay. I’m going to try to send you a postcard from Tashkent written by family trying to escape the Nazi’s. Though I read a little Yiddish, I do not know what the other language is transliterated here in Yiddish characters.

This is superb. We could really have lived without the Ben Yehuda Hebrew transliterations (“b’ezraT”, etc.) — it’s really very offensive, as though there’s something shameful about the older pronunciations, the ones our parents, grandparents, and ancestors used — and the origin of this tendency does not come from a good place AT ALL — but the technical element is beautifully done and of great practical use. Thank you for that.