By Poorvi Bellur

Part 3: William Maslow

Read Introduction; Part 1 on Shad Polier; Part 2 on Justine Wise Polier

The American Jewish Congress underwent multiple changes in

its focus over the course of the early 20th century, however it was

under the leadership of individuals like Will Maslow that it transformed into

an organ for social justice advocacy.

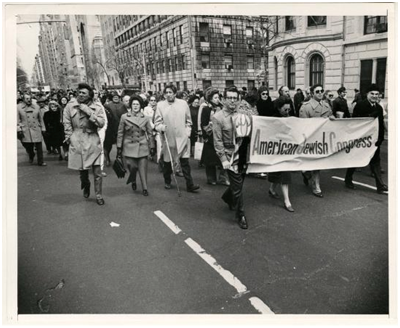

Phil Baum, Sylvia Deutsch, and Will Maslow

participate in Solidarity Day March

(American Jewish Historical Society, American Jewish Congress records, undated, 1916-2006, Call #I-77, Box 757, Folder 11)

A graduate of Columbia University Law

School (Class of ’31), Maslow worked as a reporter for the New York Times.

After some time in a private law practice, Maslow began his forays into public

justice systems when he joined the New York City Department of Investigation.

He continued to work in state government and public works and rose from trial

attorney to an Administrative Law Judge in Washington, D.C by 1941. Maslow

began to get involved with federal policy making when he was appointed Director

of Field Operations for the President’s Committee on Fair Employment Practice

(FEPC) in 1943.

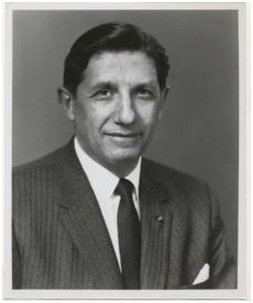

Will Maslow

(American Jewish Historical Society, American Jewish Congress records, undated, 1916-2006, Call #I-77, Box 730, Folder 20)

Maslow’s involvement with the AJC was formalized in 1945 when

he was named General Counsel of the AJC and director of the new Commission on

Law and Social Action (which he helped create). He remained counsel until 1984,

and even served as Executive Director of the AJC for 12 years of his career.

Maslow’s leadership took the AJC into the courts and the

policy making rooms in order to challenge discriminatory legislative practices.

Notably, Maslow filed a discrimination suit against his alma mater in order to

defy Columbia’s discriminatory admissions quotas. He was also involved in the

case of the Stuyvesant Town Housing Co. against who he filed a suit citing

racist policies marginalizing black tenants. Much like Polier, Maslow also

worked extensively on fair employment and housing practices.

Maslow believed in the need for solidarity among

disenfranchised groups of America and maintained “ The negroes’ fight against

discrimination in employment, housing, education is part of the struggle for

Jews for equality of opportunity in those fields”[1].

Maslow was deeply involved in the Civil rights movement of the 1960’s, and

helped organize Dr. King’s 1968 march on Washington, as well as the Little Rock

segregation case of the 50’s.

In addition to Maslow’s work as a lawyer for the AJC, the

archives of his papers reveal a great deal of scholarly work on the Civil

Rights movement and the fight for legislative reform in post-Jim Crow America.

In an extensive and comprehensive study entitled “Civil Rights Legislation,

and the fight for equality, 1862-1952”[1]

Maslow co-authored with Joseph Robison, Maslow marvels at the

nationwide drive for achievement of civil rights, calling it

the "ultimate accolade” as “it

has become a key issue in two successive presidential campaigns". He

comments on the need for integrated reform, claiming that “law itself is a

form of education and education is the prerequisite to an effective use of

law”. Keenly in tune with the conflict within the Jewish community on the

question of Civil Rights, Maslow cites the role played by societal

institutions, like the synagogue in creating the “social climate”

necessary for civil rights to flourish.

Through this study he exploresd the history of the civil

rights movement and the deeply embedded racial inequality in America, focusing

on post Civil War legislation such as black codes (prohibiting entry into

businesses that weren’t husbandry), the federal civil rights act (extended

question of citizenship), constitutional reform, the black vote and the

formation of white primaries and the restriction on black representation, and

the creation of the NAACP.

However Maslow recognizes that legislative reform will not

solve the problem of de facto violence against Black people, especially in the

South because their people “are not prepared to take a white life to pay

for a black one”. The most crucial idea presented by Maslow’s study is the

‘new violence’ of police brutality. He warns that the enemy is no longer a

lynch mob, but the “sadistic police officer”. In the year 1951 alone

there were 33 reported black deaths in police custody, most of which went

unpunished. Maslow calls for the strengthening the Civil Rights Section of the

Department of Justice coupled with the tackling of local crimes on a local

level. Ultimately, the study concludes, “nothing like the present ferment

has been seen for seventy-five years… Yet, only a beginning has been made and

many of the obstacles to complete equality loom as large as ever”. Maslow’s

understanding of race relations in America is eerily accurate in its foresight,

with the crisis in police brutality and

mass incarceration still targeting the Black community today.

[1]Maslow, Will, and Joseph B. Robison. “Civil

Rights Legislation and the Fight for Equality, 1862-1952.” The University

of Chicago Law Review 20.3 (1953), American Jewish Congress records Box 594,

Folder 1953

[1] “Will Maslow.” Jewish Currents. N.p., 30

Sept. 2016. Web. 14 Apr. 2017.

<http://jewishcurrents.org/september-27-will-maslow/>.