By Poorvi Bellur

Part 1: Shad Polier

Read Introduction

“The AJC began developing its program of using

legislation and litigation to protect human rights in 1944 and 1945. At that

time many respectable “liberal” organizations told us not to get involved in

these projects. We ignored them and went ahead. We did so not because we’re a

“liberal” organization but because we’re a Jewish one.” – Shad Polier

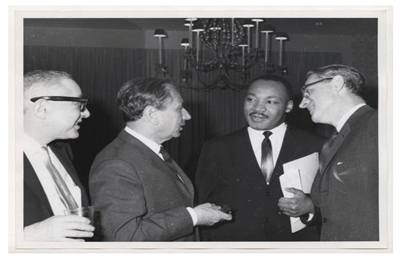

Joachim Prinz, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Shad Polier

(American Jewish Historical Society, American Jewish Congress records, undated, 1916-2006, Call #I-77, Box 740, Folder 33)

Born in Aiken, South Carolina, Shad Polier

was deeply aware of the systemic racism and resulting violence surrounding him

in his hometown, leading him to nurture his desire to someday facilitate reform

of “ not only that, but other unfair things”[1].

Mr. Polier took this drive to become one of the most well-known Jewish social

justice lawyers of the 20th century. He was in conversation with some of the

most influential thinkers and politicians of his day, including Dr. Martin

Luther King Jr., First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Roy Wilkins, Thurgood Marshall,

Hubert Humphrey, John Haynes Holmes, Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, and Adlai E.

Stevenson. A student at the University of South Caroline, Shad Polier was

horrified by the brutal racism he witnessed around him as he later recalled

“Yet by the time I’d finished at the University of South: Carolina, there had

been three separate lynchings in Aiken”[2]. After graduating from college, Polier received

admission into Harvard Law School in 1929 and received a Masters degree by

1931.

Except for a brief stint in the private

sector in New York, Polier’s career for the most part revolved around social

justice law and civil rights reform. Just two years after his matriculation

that country was consumed by the famous Scottsboro trial

and the debates raging around it. Soon after this Polier became an active

member of the NAACP, serving on its legal and education defense fund. By 1945,

he became keenly involved in the work of the American Jewish Congress under the

leadership of his father in law, Stephen Wise. As a part of the AJC, Polier went on to found

and chair of the commission on Law and Social Action of the AJC, which launched

legal battles against anti-Semitism, segregation and racism. A contributor to

the AJC’s weekly on civil liberties, Polier helped pass the first statewide

Fair Education Practices Law in 1947 prohibiting discrimination in college

admissions based on race or religion.

Roy Wilkins receiving Convention Award from Shad

Polier at National Convention

(American Jewish Historical Society, American Jewish Congress records, undated, 1916-2006, Call #I-77, Box 745, Folder 21)

The

American Jewish Historical Society’s archives containing Mr. Polier ‘s papers

offer a wealth of resources on the fight for civil liberties as well as a

window into the tumultuous relationship between the Black American and Jewish

American communities in the early 20th century. In a comprehensive

essay for an undated issue of the Office of Jewish Information (AJC) News

Release entitled ‘The Jew and the racial crisis’[1],

Polier explored the need for Jewish involvement in the Civil Rights movement,

as “not a negro struggle, but an American struggle–the struggle for human

equality and human dignity”. He expounds on the issue of school desegregation

and states “We Jews believe that there is room in America to provide a full

economic life for everyone” and criticizes the standpoint that de-segregation

will lead to the influx of slum communities into urban areas. He argues that Jews

as a part of the white community have fallen trap to this perception, despite

being separate from the white community in that they value and remember the

history of their oppression.

Polier’s

papers contain evidence of not only the AJC’s commitment to the cause of Civil

Rights, they also reveal the opposition to the AJC’s focus on Civil Rights from

within the Jewish community itself. In a newspaper article from May 14th

1960, reporter George S Schuyler reported on this alleged internal conflict,

headlined “Jews Deny ‘Heated’ Feud over Negro Rights Issue”[2].

The article cites alleged internal opposition to the organization’s emphasis on

the Civil Rights movement, with other Jewish American organizations threatening

to withdraw support if the Civil Rights movement remained a priority. An

article by Gershom Jacobson from the National Jewish Post on April 20th

of the same year asks “Should the congress give priority to a full Jewish

program or should priority be given to civil liberties and Negro rights?”[3].

Polier

and his colleagues at the AJC responded to these challenges by asserting that

the best way to ensure equal rights, safety and opportunity for Jews in America

is to correct the undemocratic nature of racist discriminatory legislation, a

goal that therefore aligned the AJC’s mission with that of the NAACP and the

leaders of the Civil Rights movement. In 1966, Polier joined Cleveland Robinson

(Secretary treasurer of District 65 of the Retail, Wholesale and Department

store union) and Samuel Hendel (Prof. of Political Science at City College) at

a Symposium on Negro-Jewish Tensions[4].

The transcript of Polier’s speech at the event preserved in his papers is most

revealing of the crisis in Jewish support for Civil Rights at the time.

[1] “The Jew and the racial crisis”, Office of Jewish

Information News Release, American Jewish Congress, Shad Polier Papers Box 7,

Folder 4

[2] “Jews Deny ‘Heated’ Feud over Negro Rights Issue”,

May 14th 1960, George S Schuyler, Shad Polier Papers Box 7 Folder 4

[3] National Jewish Post and Opinion article by Gershom

Jacobson, Shad Polier Papers, Box 7 Folder 4

[4] Transcript of Symposium on Negro-Jewish Tensions,

April 7th 1966 in the Stephen Wise Congress House (Shad Polier, Cleveland

Robinson, Samuel Hendel), Shad Polier Papers Box 7 Folder 4

[1] “Shad Polier, Lawyer, Dead; Active in Civil

Rights Cases.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 01 July 1976. Web.

14 Apr. 2017.

[2] “Shad Polier, Lawyer, Dead; Active in Civil

Rights Cases.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 01 July 1976. Web.

14 Apr. 2017.