By Lauren Gilbert, Senior Manager for Public Services, Center for Jewish History

A Survivors’ Haggadah

“And the khaki-clad sons of Israel commanded by Lt. General Truscott gathered together as was the custom in Israel, to celebrate the Passover festival.”

So begins the preamble to the so-called Survivors’ Haggadah (left), published for the first Passover after Liberation by the U.S. Army of Occupation in Bavaria, a copy of which was donated to the American Jewish Historical Society by CJH and AJHS board member Sid Lapidus.

A popular dining spot for Nazi officials during the war, Munich’s Deutsches Theatre Restaurant played host to 200 survivors and GIs for the seders 75 years ago on the nights of April 15 and 16, 1946, led by Chaplain Abraham J. Klausner, a Reform rabbi whose papers are also held at AJHS.

Rabbi Klausner had been stationed at Dachau shortly after liberation, where he worked tirelessly to reunite families and provide appropriate shelter and care for survivors. In the following months and years, he complained vociferously up the chain of army command about the deplorable living conditions in the Displaced Persons (D.P.) camps.

In Rabbi Klausner’s preamble to the Haggadah, he makes explicit the links between the suffering of the Jews under Pharaoh and the more immediate, lived experience of the Holocaust: “Pharaoh and Egypt gave way to Hitler and Germany. Pitham and Ramsees faded beneath fresh memories of Buchenwald and Dachau.” He also makes reference to the ongoing suffering of the D.P. as a “slave” contemplating his new freedom: “It was not all that he had dreamed of. He was still imprisoned in the conflict which raged among those who could grant him complete liberty.”

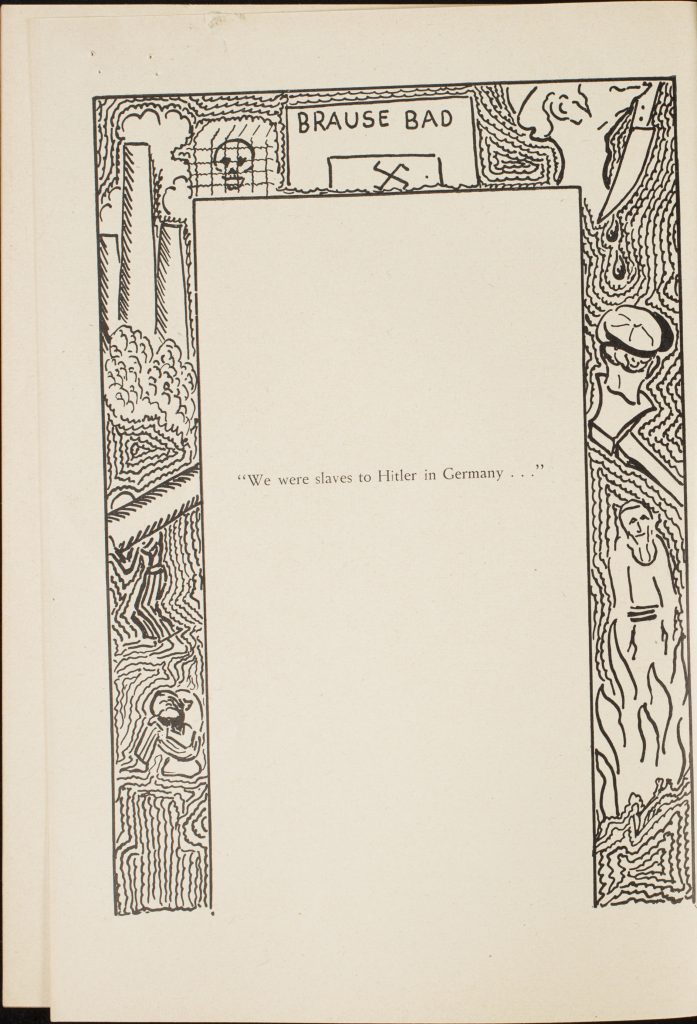

The Haggadah itself was written in Hebrew and Yiddish by Yosef Sheinson, a teacher and survivor of a slave labor camp in the Dachau complex, then living as a D.P. in Munich. The rewrite of the iconic opening line sets the tone for what is to follow: “We were slaves to Hitler in Germany.” (below)

The Passover narrative is infused with allusions to the survivors’ plight: “The surviving remnants were coming out of the caves, out of forests, and out of death camps, returning to the land of their exile. The people of those lands greeted them and said: ‘We thought you were no longer alive, and here you are, so many of you.’ And they sent the survivors all sorts of messages, telling them to leave the land, even killing them. And the people of Israel ran for their lives; they were sneaking across borders only to be robbed of everything they had.”

In a shockingly ironic inversion of the original message of Dayenu, Sheinson lists historical horrors from the Crusades through the Holocaust instead of reciting God’s miracles: “Had He given us Hitler, but no ghettos, it would have been enough. Had he given us ghettos but no gas chambers and crematoria, it would have been enough….”

The song ends with a conclusion quite different from the standard hope for God’s deliverance: “All the more so, since all these have befallen us, we must make Aliyah, even if illegally, wipe out the Galut (exile), build the chosen land, and make a home for ourselves and our children for eternity.”

In selecting this iconoclastic text for the 1946 seders, Klausner, who was not averse to breaking rules to achieve higher objectives, was acknowledging that this would be no ordinary seder, and that giving thanks for deliverance would be complicated and tinged with bitterness.

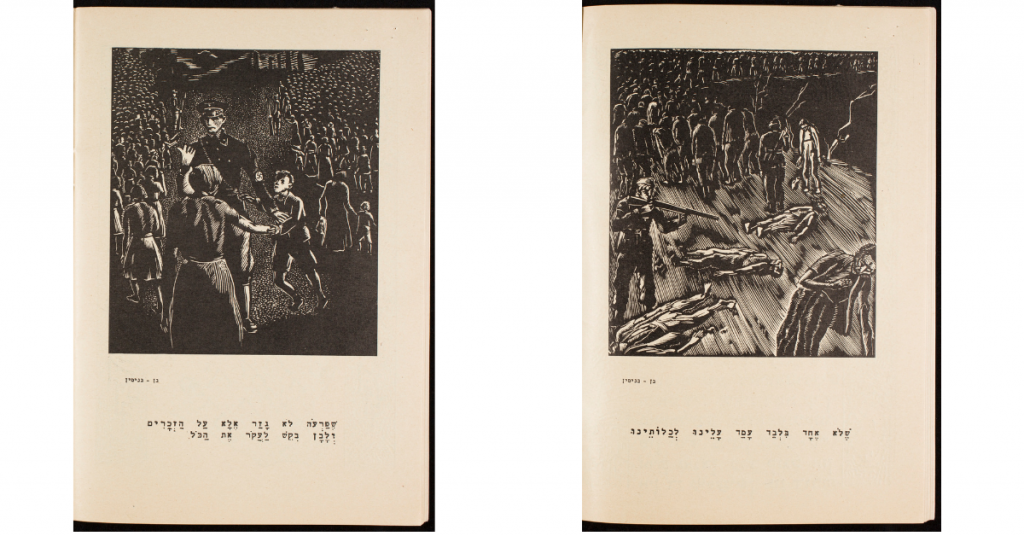

Sheinson also designed and illustrated the Haggadah, including the expressionistic page borders. The seven striking woodcuts, which depict scenes of Jewish suffering in the camps, were created by the artist Miklos Adler, a survivor from Debrecen, Hungary who had been interned at Theresienstadt. (below)

An 18-year-old survivor in attendance that April remembered asking himself: “What is the difference between this night and any other [seder] night? The first and most painful difference was the absence of small children who traditionally asked the four questions. The Nazis murdered them all.”

Among Klausner’s personal correspondence at AJHS is a letter he wrote to a friend from Dachau on August 1, 1945, eight months before the Munich seders, in which he laments: “It is in this area that I found that not even a single Jewish child was left alive. Read that last sentence again Bob ﹘ I am not drunk with words ﹘ not a single Jewish child is alive in Bavaria.”

Dozens of letters of praise and thanks were sent to Klausner and his superiors by colleagues in the army and various service agencies, attesting to his character and achievements:

“You took broken human beings and fragments of Jewish life, and built them into a community.”

“Yours has been the ministry of service, the ministry of help to the needy, and the alleviation of suffering of those in pain.”

“That boy deserves the thanks of thousands upon thousands of Jews. He has literally saved hundreds of lives.”

“The work he did was nothing short of heroic.”

In this second year of celebrating Passover in the midst of a modern-day plague, let us remember the resilience of the ragtag crowd of survivors and GIs who came together in the Deutsches Theatre Restaurant 75 years ago to celebrate “the miracle of freedom,” and let us give thanks to Rabbi Klausner and the “khaki-clad sons of Israel.”

See a complete digitized version of the haggadah here. All images courtesy of AJHS.

Sources: