June 17, 2024

By Ishai Mishory, 2023-24 Center for Jewish History Lapidus Graduate Fellow

The Political Economy of Classification: Jewish Bibliographers Write about Gershom Soncino

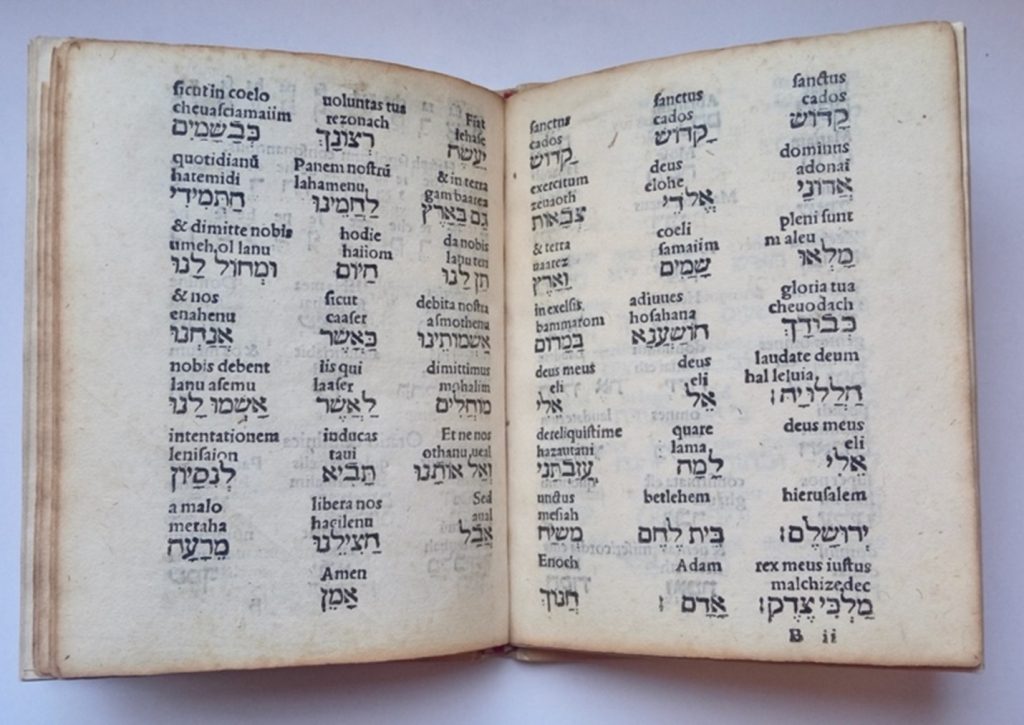

What constitutes “Jewish knowledge”? Who decides what is a “Jewish” versus a “Non-Jewish” book or title? Should the decision be based on subject matter (a.k.a, “Rabbinic material”), or maybe on language (Yiddish and Hebrew, presumably – but not Italian)? On the identity of a book’s writer? Maybe its editor, its readers, or its printer?

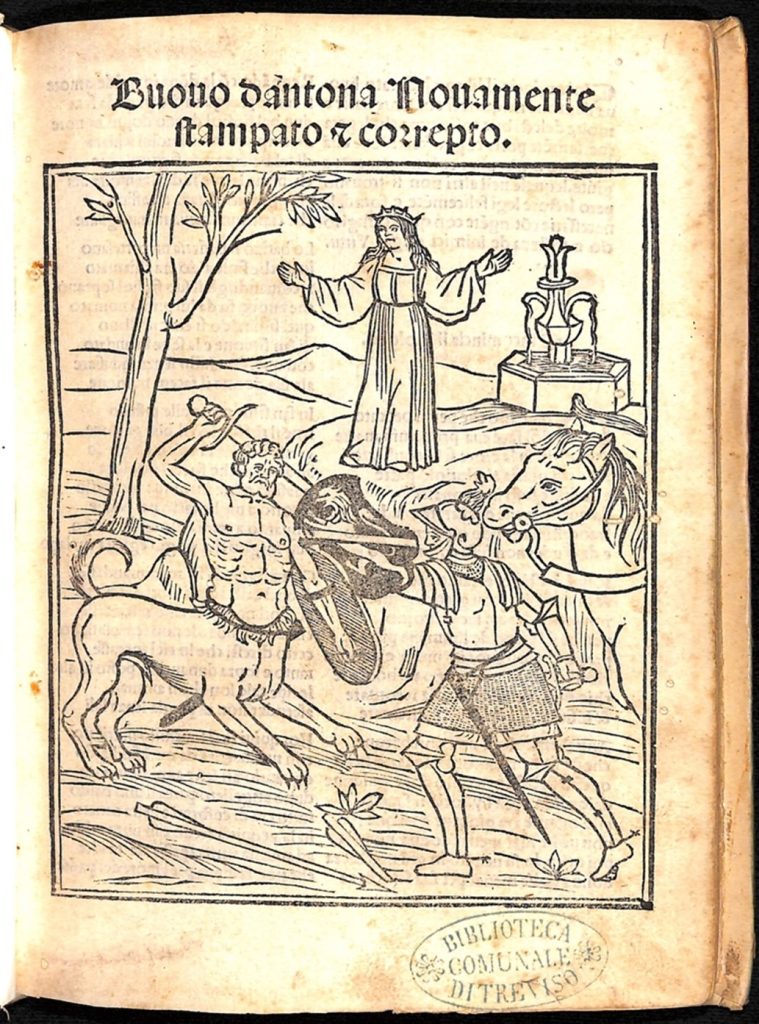

Examining these choices not simply as so much scientific list-making but as a literary discourse reveals the personalities and proclivities of the different writers as constituting different possible images of the Jewish past, and of Jewish identity itself. Rather than simply reflecting an already-extant body of “Jewish material,” the inclusions and, perhaps most importantly omissions practiced by these writers and librarians – from Moritz Moritz Steinschneider (1816–1907), an erudite scholar of large swaths of Jewish (and indeed, human) history to practitioners of much more specialized purviews, like Russian-born Rapha‘el Nathan (Nata) Rabinovitch (1835–1888), in his case the printing history of the Talmud – arguably constituted it. For instance, while some of them chose to work with different “national” Jewish languages, supplying historical credence to competing (Hebrew/Yiddish) national-linguistic projects, others focused on specific genres, often occluding competing material. It has taken recent scholarship into Jewish literatures from the early modern period, for example, to address books produced in that period – often in vernacular languages, read by women, exhibiting ‘low’ literary quality or accompanied by robust illustrations. The mostly-German Jewish bibliographers knew of their existence but deemed them unworthy.

Much hangs on a critical take on “Jewish bibliography” when dealing with the experiences of Italian and Ottoman early modern Jews. Is a book including woodcut illustrations of the Life of Christ to be deemed “Jewish” if its printer were a devout Jewish man? What about the same printer dealing with Latin humanist material? Alternately, did the Jews of Renaissance Italy read and enjoy those illustrated tales of chivalric derring-do so wildly popular at the time in their original vernacular, or did they have to wait for that literature to be “Judaized” for their benefit? The archive offers some surprising answers, but they demand a move beyond Rabbinics-centered, essentializing, nationalist-linguistic readings to a more creative, generous. and expansive view of Jewish identity and history.