By Margaret Tilley, Genealogy Specialist and Curatorial Projects Assistant

A Shul on Every Corner: Remembering Synagogues of the Lower East Side

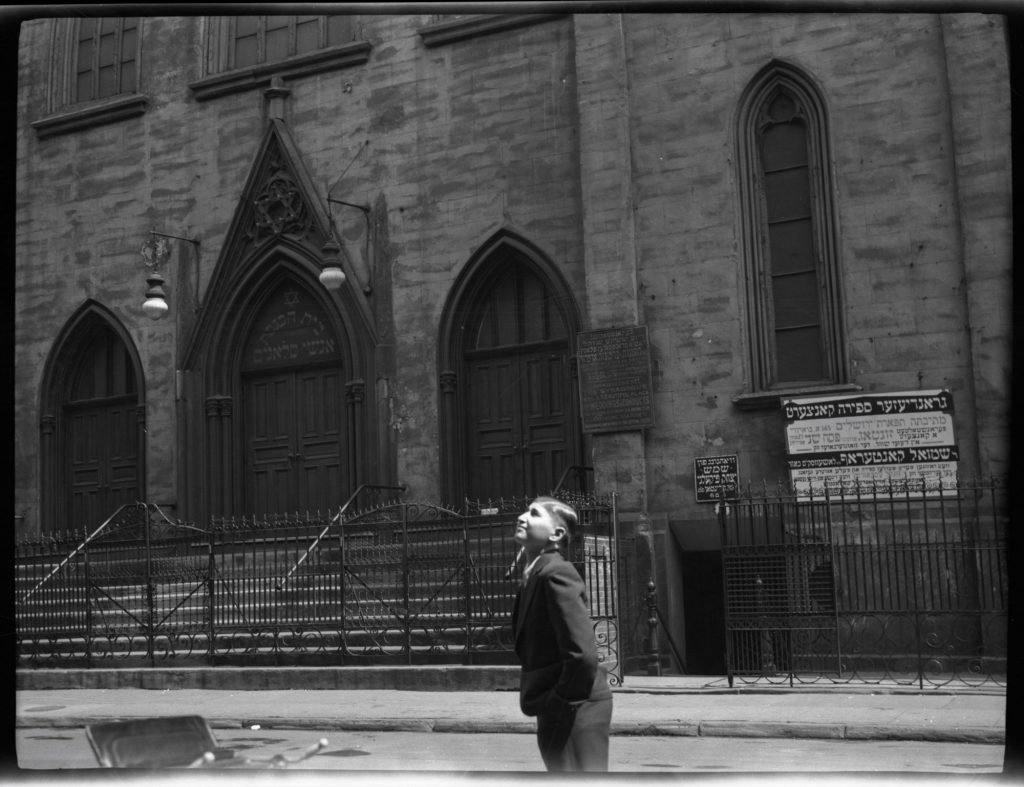

Above, a boy stands before the oldest surviving synagogue building in New York City, located at 172 Norfolk Street. What was then a neighborhood fixture brimming with debates about Jewish identity and rite has, like many other Lower East Side synagogues, since faced abandonment and rediscovery. This blog post explores the diverse life cycles of seven Lower East Side Synagogues, with highlights from the collections of the Center for Jewish History’s partner organizations.

Anshe Chesed, 172 Norfolk St.

The congregation Anshe Chesed formed in 1828, but did not build this Gothic Revival synagogue until 1849. Since the building’s erection, it has housed numerous congregations, including Anshe Chesed, Congregation Ohab Zedek (First Hungarian Congregation), and Anshei Slonim. After membership dwindled following WWII, the building sat abandoned for years and narrowly escaped demolition when the Spanish-Jewish artist Angel Orensanz purchased it in 1986. Today, the building is known as the Angel Orensanz Foundation. It hosts performances and events, and Jewish luminaries like Mandy Patinkin, Elie Weisel, and Arthur Miller have performed in the building.

The story of Anshe Chesed’s founding reveals that Lower East Side synagogue culture—and perhaps American synagogue culture at large—has its roots in disagreement.

From 1654 to 1825, Shearith Israel was the only congregation in New York City. Founded by Sephardic Jews who had arrived during the colonial period, Shearith Israel followed the Portuguese “minhag,” or rite. Though this satisfied the predominantly Sephardic population of Jewish New York for over 100 years, by the nineteenth century, a growing German-Jewish population sought to create a synagogue that matched the Ashkenazi minhag they had practiced in the old country.

In 1825, Ashkenazi members of Shearith Israel broke off to create Congregation B’nai Jeshurun. But even within this growing Ashkenazi group, disagreement remained. B’nai Jeshurun practiced a form of English minhag, which frustrated those who joined the congregation looking for German or Polish minhag. Only three years after B’nai Jeshurun’s founding, a group of German, Dutch, and Polish Jews left it to form Anshe Chesed in 1828. Within Anshe Chesed, rites and rules shifted as the makeup of the congregation changed. They moved from a generic ‘Ashkenaz’ minhag to the specific customs of Furth, Bavaria as the Bavarian membership grew, and later adopted the Vienna minhag.

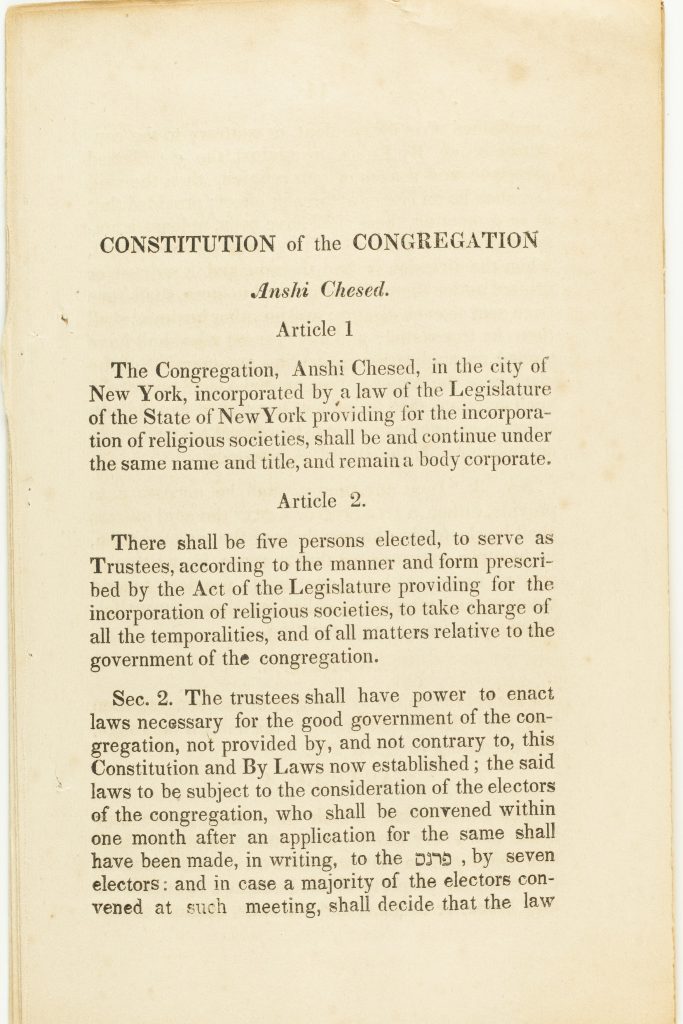

Membership also wielded considerable power over synagogue affairs at Anshe Chesed. The congregation’s constitution [see below] established that five trustees, elected by members, would have the power to enact laws for the synagogue. Outside of the synagogue’s official laws, surviving minute books from Anshe Chesed show a remarkably engaged membership that formed special committees to discuss a range of issues— from whether hanging a flag bearing the image of an eagle over the ark amounted to idol worship, to reining in the behavior of their cantor, who was known to gamble at all hours of the night.

Anshe Chesed represents a turning point in the history of Lower East Side synagogues. By the mid-nineteenth century, growing immigrant populations inspired new congregations that would best represent their own customs. Inside these new synagogues, the laity embraced experimentation and debate, using its power to work through the challenges of practicing Judaism in a new land.

Adath Jeshurun of Jassy/Erste Warschauer, 58 Rivington St.

The synagogue at 58 Rivington St—occupied by Adath Jeshurun of Jassy and, later, the Warschauer Synagogue—provides a window into the distinct religious culture Eastern European Jewish immigrants built upon their arrival in New York.

By the late nineteenth century, the pace of change on the Lower East Side had become exponential. The 1881 assassination of Tsar Alexander II prompted widespread violence against Jews in the Russian Empire, sparking a great wave of Jewish emigration from 1881 to 1924. During this period, roughly one third of East European Jewry left their places of origin, with most emigrants to America arriving in New York.

Eastern European Jews were not interested in joining German-Jewish congregations, which had implemented many features of Reform Judaism by this time. Instead, these Eastern European immigrants established their own congregations, where they could practice a traditional “Old World” orthodoxy. With such a rapid influx of East European Jews, migrants did not have to choose a regional or national rite to follow as their German-Jewish predecessors did, but could establish synagogues made up of their fellow townsmen, following the town’s particular customs.

Though Adath Jeshurun of Jassy formed in 1886, composed of immigrants from Jassi (now Iasi), Romania, it did not move into this building at 58 Rivington St. until 1904. Previously, the congregation had met in a building on Hester St. The move to Rivington St created quite a spectacle, as members took the Torah scrolls on a “parade” towards the new building. The parade, documented in the New York Times, drew a significant crowd: “Three hundred policemen under command of Inspector Schmittberger escorted the marchers to see that no disorder occurred in the ranks of the thousands of onlookers, but there was not the slightest sign of disorder in the entire four hours that the ceremony took up,” the Times reported.1 Upon arriving at their new building, members of the congregation made speeches, sang the “Star-Spangled Banner,” and unlocked the door to their new sanctuary.

This congregation’s spectacular move from one building to another highlights a key aspect of American synagogue culture as it emerged on the Lower East Side. The sheer density of buildings and of immigrant populations meant that congregations could relatively easily move, split up, or join together. The built environment of the Lower East Side could be incredibly restrictive—think of packed tenements and poor sanitation—but this same density afforded immigrants a freedom to easily switch congregations, establish their own shuls, and observe the Sabbath laws of the Old World, with Kosher food always nearby and dozens of synagogues only a few blocks from home.

By 1912, Erste Warschauer (First Warschauer Congregation) had moved into 58 Rivington St. Below, see a photo of their congregants ca. 1944.

Congregation Kehila Kedosha Janina, 208 Broome St.

Congregation Kehila Kedosha Janina reminds us that any attempt to categorize historic Lower East Side synagogues—as Sephardic or Ashkenazi, as Reform or Orthodox, or as German-Jewish or East European—fails to encompass the true diversity of the neighborhood’s synagogue culture.

At the same time as a great wave of East European Jews came to New York around the turn of the century, so did many Levantine Jews from Syria, Turkey, Palestine, Iraq, and the Balkans. In addition to this group were the Romaniote Jews of Greece. The Romaniote story goes back to the year 70 CE, when the Holy Temple of Jerusalem was destroyed. Legend says that a group of Jews were sent on a slave ship to Rome, but landed in Greece and settled there in the city of Janina, where they remained for nearly two thousand years. At one point, this city had the largest Jewish population in Greece. Known as Romaniote Jews, the Jews of Janina are neither Sephardic nor Ashkenazi, and practice a unique Romaniote rite.

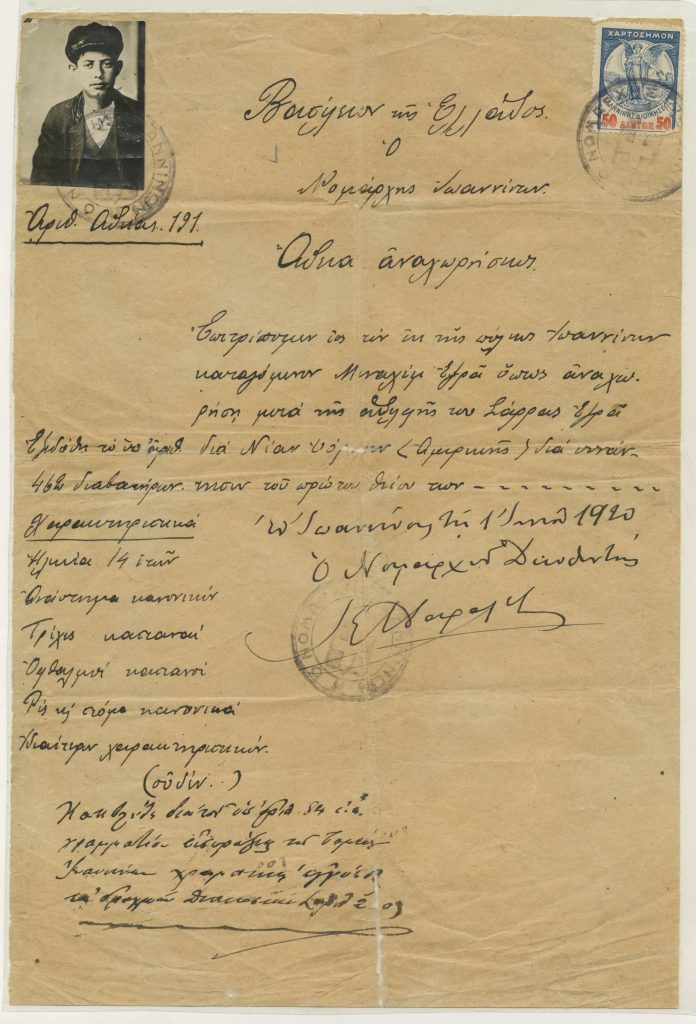

Their synagogue, Kehila Kedosha Janina, still operates as a museum and house of worship. It is the only synagogue created by the Jews of Janina in the Western Hemisphere. The congregation itself formed in 1906, when many Levantine Jews were arriving [see travel document below], but did not erect this building until 1927. The synagogue is designed as a replica of the synagogue of Janina, with one important exception. Romaniote rite dictates that synagogues run east to west, with the bimah on the west wall, but the layout of this lot forced Kehila Kedosha Janina to build their synagogue north to south, with the ark at the north wall and the bimah in the center. Once again, some elements of Old-World rite remained while others transformed in America.

As Jewish immigrants continued to arrive in New York and settle on the Lower East Side, sections of the neighborhood became dominated by the Jews of Galicia, or those of Hungary; Kehila Kedosha Janina sits in the center of the old Romanian/Levantine section, despite its members not quite coming from either of these groups. Evidently, the neighborhood’s culture and geography allowed Jews of different backgrounds to coexist while still practicing distinct forms of Judaism.

Congregation Kahal Adath Jeshurun with Anshei Lubz, 12 Eldridge St.

While smaller congregations usually tended to the needs of recently arrived, working-class immigrants, other congregations used their synagogues to articulate rising status in American culture and business. Congregation Kahal Adath Jeshurun Anshei Lubz, often known as the Museum at Eldridge Street, is one such congregation [see below].

The Eldridge Street synagogue was built in 1886 and came out of a merger between the congregations Adas Jeshurun and Anshei Lubz. Though these congregations began with sparse resources, renting spaces on Pearl and Allen Streets, by the time they planned the building on Eldridge Street, the membership included some notably successful men of the Lower East Side, like the banker Sender Jarmulowsky and the real estate businessman David A. Cohen. These men had emerged as members of a growing downtown elite who found success before the influx of East European Jews around the turn of the century.

With a membership of upwardly mobile Jews like these two men, Kahal Adath Jeshurun could make its synagogue a spectacle. Construction of the edifice cost $85,000—about $2.8 million today—and members paid to have a hand-carved walnut Holy Ark imported from Italy. The building’s architects, the Herter brothers, designed the building to resemble Moorish precedents from Europe and Uptown Manhattan. Moorish architecture refers to the style that developed when Spain was under Muslim rule and its Jews enjoyed considerable freedom. Using this style was a way to invoke a golden age of Jewish religious freedom in a new era. At the same time, the synagogue’s Moorish style resembled many of the affluent German-Jewish congregations that had moved Uptown. The style thus tied the Eldridge congregants to a story of Jewish success, in contrast to what they perceived as Jewish struggle at many of the smaller Lower East Side synagogues.

Indeed, there was a barrier to entry at Kahal Adath Jeshurun that did not exist at many of the smaller synagogues: members were expected to purchase a permanent seat in the sanctuary at a cost of $200-1100. This sum was well out of reach of most tenement-dwelling, laboring migrants, but was evidently affordable to the Lower East Side’s emerging business class.

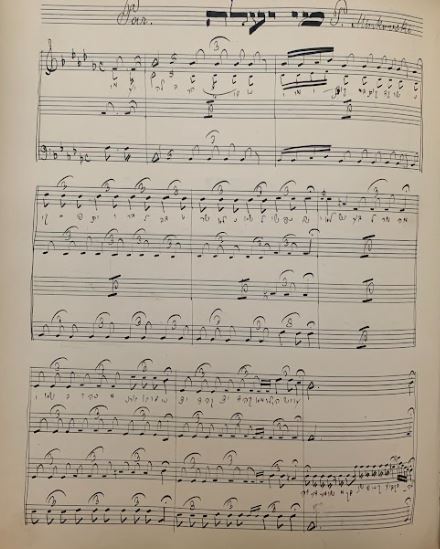

Displays of status extended beyond adornment of the synagogue. In the early 1900s, members hired Pinchas Minkowsky, renowned cantor from Odessa, for an unprecedented sum [see musical composition below]. The congregation not only bought Minkowsky out of his Odessa contract for 1000 rubles, but also paid him $2,500 per annum with a $500 yearly bonus. All that came on top of the cost of recruiting a choir to sing with Minkowsky. The move sparked what scholars have called a “cantor craze,” as affluent synagogues competed to secure impressive cantors who would draw attention and raise the congregation’s status.

Kahal Adath Jeshurun’s emphasis on ornamentation and status did not undermine its religious function, but instead demonstrates the flexibility of Jewish tradition in a new land, as congregants chose to focus their efforts and finances on creating a truly spectacular place of worship, where members could see, be seen, and pray.

Like many other Lower East Side synagogues, Kahal Adath Jeshurun declined throughout the twentieth century. Unusually, though, it was “rediscovered” in 1971 by historian Gerald Wolfe, who inspired a multi-decade, $20 million restoration project which allowed the sanctuary to reopen in its former splendor by 2007. Today, the Museum at Eldridge Street holds tours and educational programs to introduce visitors to the immigrant Jewish past.

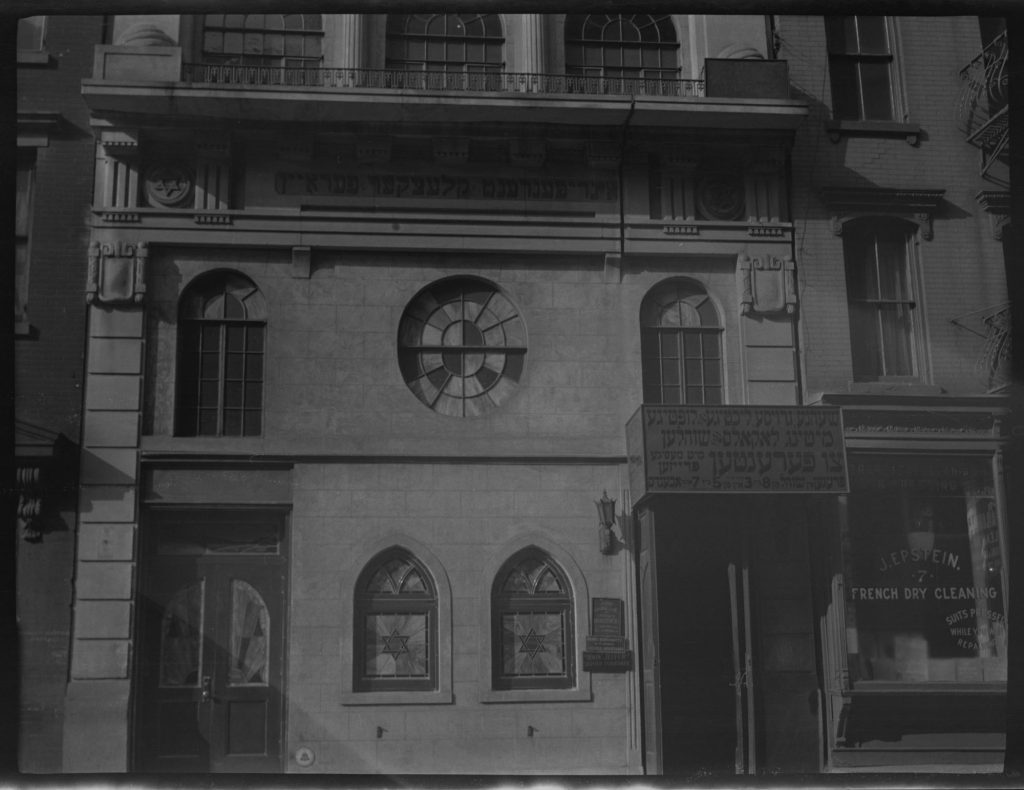

Independent Kletzker Brotherly Aid Association, 5 Ludlow St.

As the previous synagogues demonstrated, there was no one way to practice Judaism on the Lower East Side. Immigrants found considerable freedom in synagogues, as congregants devised rules, geography allowed for frequent change, and streams of Jewish immigrants from different places coexisted alongside one another. Many congregants wielded this freedom to support one another in both religious and secular matters.

Above, see a historical photo of the Independent Kletzker Brotherly Aid Association. It is now a Chinese funeral parlor, but the Association’s name remains carved into the edifice towards the top of the building. The congregation’s name indicates that it is a landsmanshaft organization. Landsmanshaftn, which loosely translates to “hometown societies” in Yiddish, were organizations of people who had come from the same town in Eastern Europe—in this case, Kletzk, Belarus. Though some landsmanshaftn were entirely secular, primarily serving as a community organization and source of financial support for fellow townsmen, others functioned exclusively as congregations. Most landsmanshaftn fell somewhere in between, tending to both religious and secular life.

The Kletzker Association poured its energy into an issue where religious and secular life met: Jewish burial. Many landsmanshaftn pooled members’ funds to purchase dedicated sections of Jewish cemeteries for fellow townsmen’s burials. Considering the sometimes exorbitant cost of funerals, burials, and headstones, Jewish immigrants who arrived with little wealth were able to carry out burial customs according to Jewish law by drawing upon the aid of their fellow townsmen.

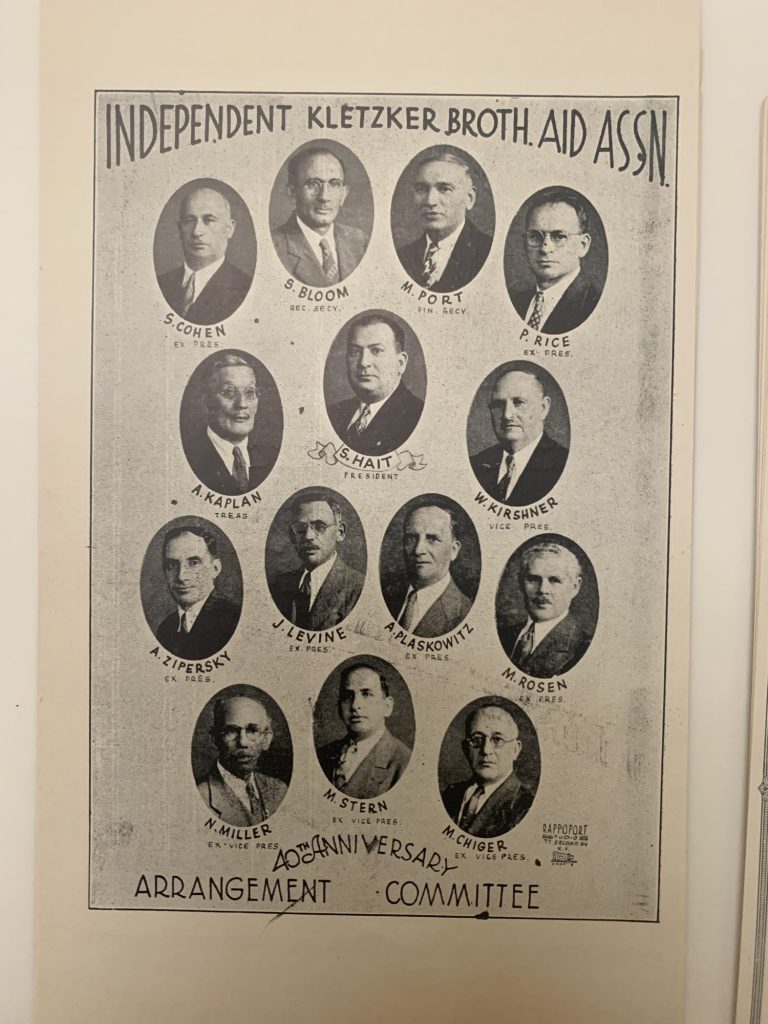

A ledger in the Kletzker Association’s papers documents the deaths of members. Each entry includes the name, date of death, and resting place of a member. One can imagine the relief that the Association gave grieving family members by taking care of burial arrangements in an organized and cost-effective way. [See anniversary publication below.]

Still, membership in landsmanshaftn meant far more than a logistical or financial benefit to members. Landsmanshaft congregations above all offered their members a chance to connect with the world they had left behind. Meeting with fellow immigrants from Kletzk on a regular basis would be a respite from the dizzying new environment. The group could reminisce about stories from their town and stay aware of changes through landsmanshaft contacts in the old country. Landsmanshaft congregations like this one allowed populations that had uprooted themselves from often isolated East European shtetls to come together and articulate an identity as American Kletzkers.

Young Israel Synagogue, 225-231 East Broadway

As the twentieth century progressed, the makeup of the Lower East Side changed, and so did its synagogues. The 1924 Johnson-Reed Immigration Act set strict quotas for immigration based on national origin, which meant that far fewer Jewish immigrants arrived each year. Without fresh ranks of Yiddish-speaking, Sabbath-observant immigrants around, the American-born Jews of the Lower East Side often felt that Old World Orthodoxy and the Yiddish and Hebrew languages were beyond them. In his 1930 book East Side Epic, Harry Rogoff touched on this issue: “The old-fashioned religious Jew saw his traditions discarded and even ridiculed. He saw his children drift away from him to pick up strange new ways. Even the more modern and liberal Jew was grieved at the tendency toward assimilation on the part of the younger generation.”

Seeing that the Lower East Side’s Jewish culture might taper out in an assimilated, American-born generation, a group of young people came together to found Young Israel, an organization dedicated to bringing young people back into the fold of traditional Judaism. In 1912, Young Israel began by hosting discussions about various Jewish matters in rented shuls around the neighborhood. By 1921, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society had moved out of the former building at 225-231 East Broadway, and Young Israel moved in, establishing its own synagogue.

The founders of Young Israel worried that the American-born generation would be won over by Reform Judaism, which was growing at this time under the leadership of Stephen S. Wise of the Free Synagogue. To counter the Reform influence, Young Israel held services where English would be spoken instead of Hebrew, congregational singing was permitted, and women were especially encouraged to participate. Implementing these changes in an otherwise traditionally Orthodox service, Young Israel suggested, could make Orthodoxy appealing and intelligible to an American-born generation.

In their 1937 souvenir journal, Young Israel President I.J. Lurie wrote, “When we have succeeded in organizing our youth under the banner of Orthodoxy, all our Jewish problems and difficulties will be solved by themselves…,” fostering in members “…a feeling of solidarity and fraternity through their devotion.”

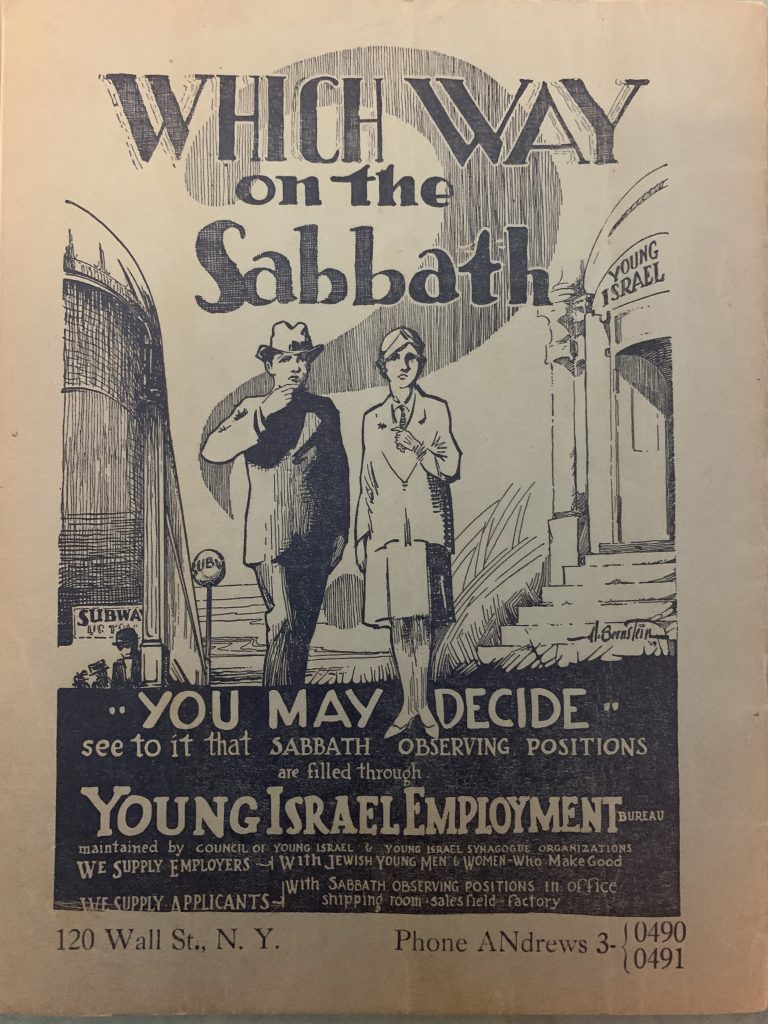

To create this sense of fraternity, Young Israel devised social initiatives like literary groups and day camps. One particularly important project aimed to allow young Jews of the neighborhood to observe the Sabbath. Under economic stress, many downtown Jews could not afford to take Saturdays off of work, and few employers closed on the Sabbath. In 1925, Young Israel created its Sabbath Employment Office, which sought to match individuals with Sabbath-observant jobs that would permit employees to attend shul and abstain from work on Saturdays [see below].

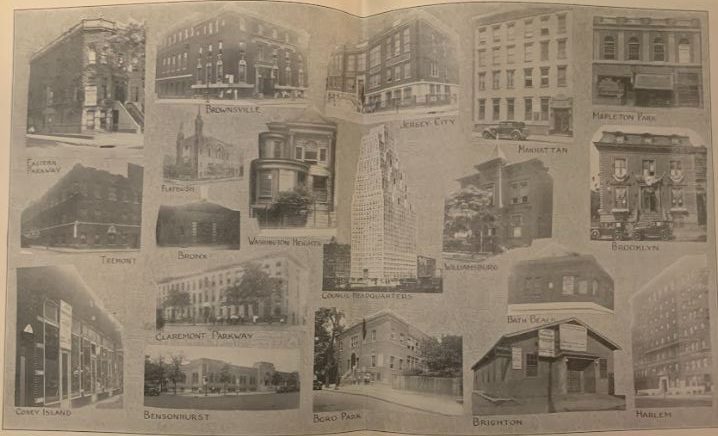

As New York City’s Jewish population spread beyond the Lower East Side [see below], Young Israel branches appeared from Bensonhurst to Harlem to Jersey City, continuing the founders’ efforts to draw young people towards traditional Judaism. Young Israel continues to advocate for traditional Judaism today in its 125 nationwide synagogues. Young Israel continues to advocate for traditional Judaism today in its 125 nationwide synagogues, although the original building at 225-231 East Broadway is no longer standing.

Stanton Street Shul, 180 Stanton St.

By the mid-to-late twentieth century, Jewish immigrants moved out of the Lower East Side en masse, leaving behind many of the synagogues discussed above. Several congregations held closing meetings before disbanding, as larger “synagogue-centers” emerged in neighborhoods beyond the East Side.

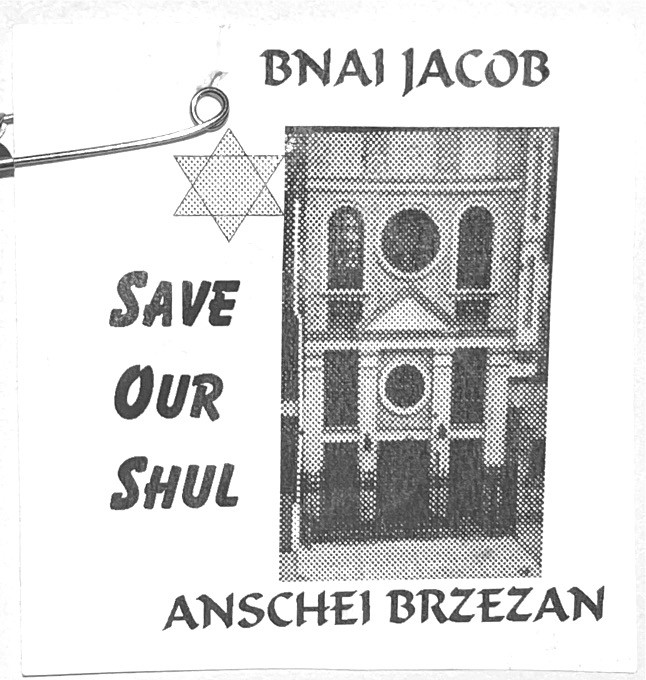

For the congregations that remained through the East Side’s evolution, protecting the synagogue could be a battle. The Stanton Street Synagogue, often known as the Stanton Street Shul, fought one such fight.

Founded in 1894 by immigrants from Brzezany (now Berezhany, Ukraine), the congregation purchased its own synagogue building in 1913 at 180 Stanton St. In line with the neighborhood’s demographic shifts, the congregation’s membership declined by the mid-twentieth century. To bolster its ranks, the congregation merged with B’nai Joseph Dugel Macheneh Ephraim, which represented Jewish communities of Riminiv and Blujhev. Ironically, what began as a story of endless congregational secessions ends as a story of protective congregational mergers. A neighborhood bustling with religious opportunity morphed into a neighborhood defending its sacred places through moves that forced compromise among coreligionists who came to share space.

The Stanton Street Shul fared well through the later twentieth century under the leadership of Rabbi Joseph Singer, whose magnetic personality led many to call the synagogue “Rabbi Singer’s shul.” One day in 2001, however, congregants were surprised to find their synagogue locked. On the door, a sign indicated that Rabbi Singer had sold the building to a Brooklyn realty company without consulting the congregants. Members petitioned the Court of the City of New York about the sale, stressing that the building’s deed states that the building is owned by the congregation itself, not by Rabbi Singer.

In her petition, Iris Claire Blutreich explained the enormous loss that would follow the building’s sale. “The congregants are of all ages and backgrounds,” she wrote. “Many have watched helplessly during the Holocaust as their families were murdered. Others faced extreme conditions in the work camps of Siberia. Every morning at 6:30a.m. there is a minyan of at least 10 men who pray… Saturday at 9:30 a.m. there are services for 40 to 60 worshippers.” [See flyer below.]

Ultimately, the membership won back their synagogue, which remains active today and is a testament to the tenacity of Lower East Side synagogue culture.

The synagogues discussed in this post that still hold services—the Stanton Street Shul and Congregation Janina—may be exceptions to the widespread decline of Lower East Side synagogues. But even as the neighborhood’s religious culture has faded, we may look at the synagogue buildings that remain just as immigrant generations did: as portals to a left-behind world.

I’ve lived on the Lower East Side for sixteen years, and it’s wonderful to read about the history of my neighborhood.

I show every one (including a few more) on the Synagogues of the Lower East Side walking tour I do for the Lower East Side Jewish Conservancy and Museum at Eldridge Street. They will start up again in Fall. By the way, the Young Israel Synagogue on East Broadway is no longer there.

Yes, thanks! We edited the text to make that more clear.

I grew up on the lower east side.

I attended many synagogues in that neighborhood including the Young Israel, the Bialystocker synagogue, the Downtown Talmud Torah synagogue, whose hebrew school I graduated from in June1964. I had my aufruf at Beth Medrish Hagadol on Norfolk Street.