By Lauren Gilbert, Director of Public Services

A Yom Kippur Blood Libel in New York

Two days before Yom Kippur in 1928, a four-year-old girl named Barbara Griffiths wandered into the woods near her home in Massena, New York, a small town in St. Lawrence County along the Canadian border. After a day of fruitless searching by crews and volunteers, the New York State Police took over the investigation.

While historically, blood libel accusations coincided with Passover (invoking the purported use of Christian blood in making matzah), by the end of the first day a rumor started spreading about a connection between the girl’s disappearance and the upcoming Jewish holiday.

The mentally ill adult son of the president of the local synagogue was detained by police, causing some alarm. Other Jews were questioned, and at least one Jewish home was searched, in a town of only 19 Jewish families. A state trooper showed up at the home of the local rabbi, who was called to the police station as angry crowds gathered outside.

By 4pm on the second day, the missing girl was spotted wandering unharmed along the side of the road, and the whole affair was over by the start of the Kol Nidre service.

The night of the girl’s disappearance, as accusations started swirling, an emergency meeting was convened by the leaders of the Jewish community, who placed a call to Louis Marshall, a prominent Jewish civil rights attorney in New York City and founder of the American Jewish Committee. Marshall dispatched Boris Smolar of the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, who filed several reports from Massena, which were picked up and amplified by news outlets around the nation.

A New York Times article on October 8 reported that the blood libel charge was “assailed by rabbis in their sermons,” quoting a Bronx rabbi who “urged Jews to invite members of other creeds to their religious services, so that superstitions concerning Jewish customs might be destroyed.” 1

An October 12 editorial in The Jewish Exponent mused bitterly, “What comfort, the news of this incident, when carried abroad, will bring to the Hitlerites, the Jew-baiters of the old countries of Europe!” The piece concludes, “It was an act of Providence that the little girl was found so quickly, otherwise who can tell what the mob might have done to the panicky Jews in the small town?” 2

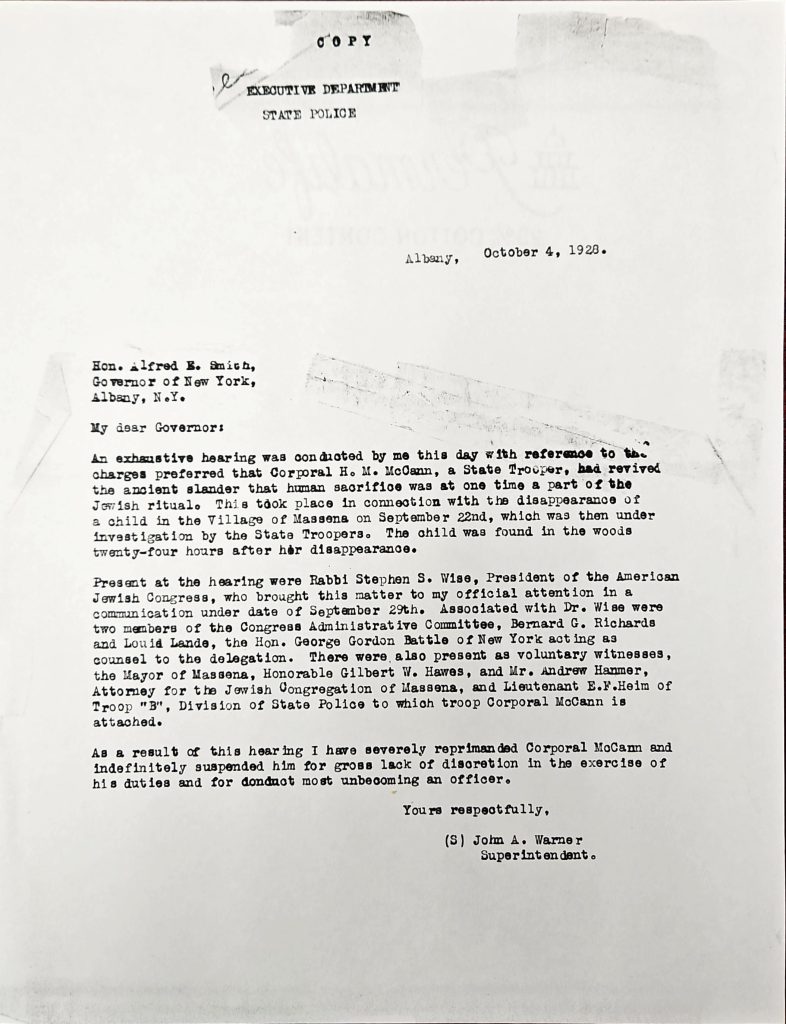

An October 4 letter from John A. Warner, Superintendent of the New York State Police, to New York State Governor Alfred E. Smith, a copy of which can be found in the Bernard G. Richards Papers (P-868) at the American Jewish Historical Society, attests that “an exhaustive hearing has been conducted by me this day with reference to the charges preferred that Corporal H.M. McCann, a State Trooper, had revived the ancient slander that human sacrifice was at one time part of the Jewish ritual.” Warner goes on to confirm that the trooper had been “indefinitely suspended” for “gross lack of discretion in the exercise of his duties and for conduct most unbecoming an officer.”

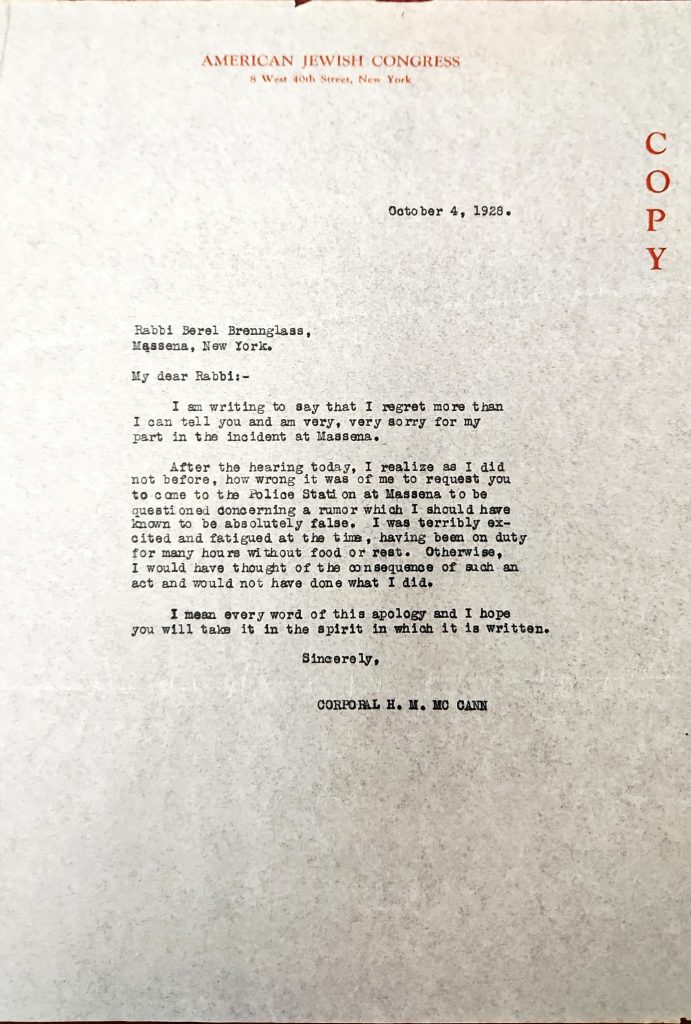

Alongside this missive is a copy of the October 4 letter of apology from the state trooper to the local rabbi he had questioned about the girl’s disappearance [see below]. It begins, “I am writing to say I regret more that I can tell you and am very, very sorry for my part in the incident at Massena.” He goes on to blame fatigue and excitement, along with lack of food, for his poor judgment.

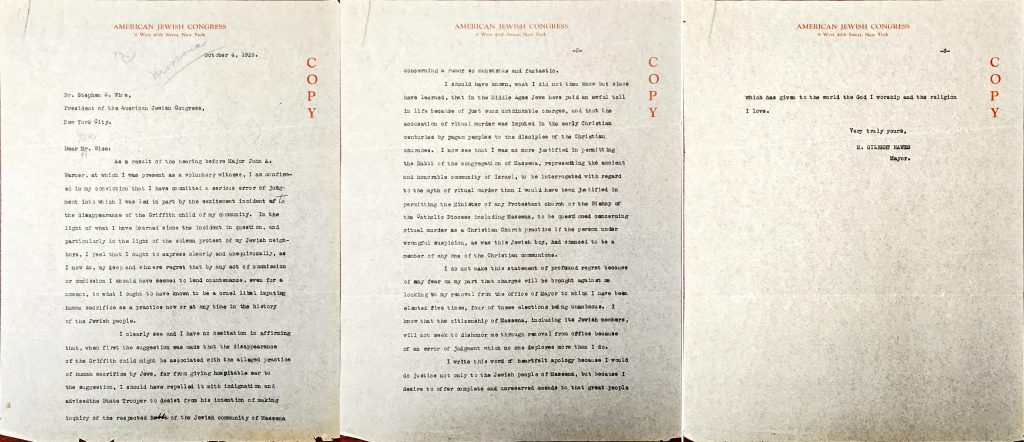

The same folder also contains a copy of the October 4 letter of apology penned by H. Gilbert Hawes, Mayor of Massena, and addressed to Rabbi Stephen Wise, President of the American Jewish Congress [see below]. Hawes admits to “a serious error of judgment,” acknowledging it to be “a cruel libel imputing human sacrifice as a practice now or at any time in the history of the Jewish people.”

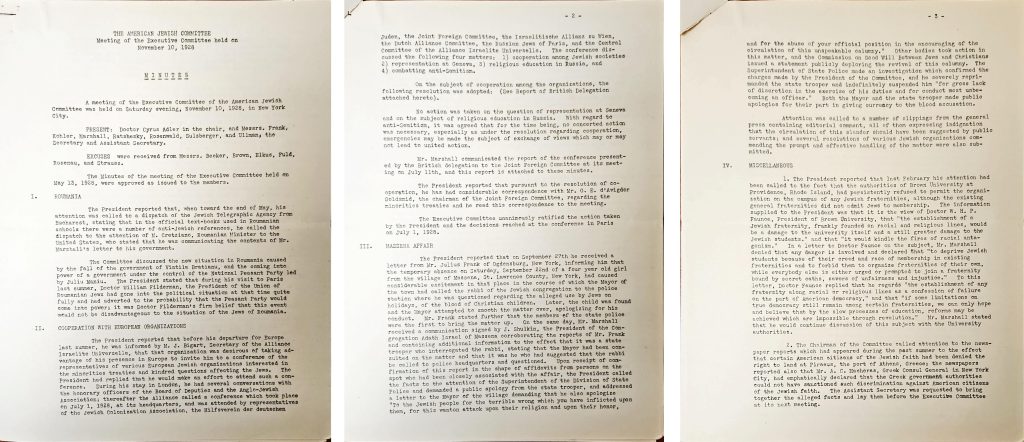

The minutes of a November 10 meeting of the Executive Committee of the American Jewish Committee [see pages 2 and 3, below], preserved in the Admiral Lewis Lichtenstein Strauss Papers (P-632) at the American Jewish Historical Society, recap the entire affair, and remark on the responses to the incident in the general press, “all of them expressing indignation that the circulation of this slander should have been suggested by public servants.”

An October 11 editorial in The American Israelite credited the quick resolution of the Massena incident to “the common sense of the American public, a virtue which has stood many a traduced group and individual in good stead.” 3 This homegrown blood libel was quickly and decisively repudiated, and never repeated on U.S. soil. Nearly 100 years later, in an era of rising antisemitism, it can be read as a cautionary tale.

Further readings:

Berenson, Edward, The Accusation: Blood Libel in an American Town. W. W. Norton & Company, 2019.

Friedman, Saul S. The Incident at Massena: The Blood Libel in America. Stein and Day, 1978.

Jacobs, Samuel J. “The Blood Libel Case at Massena- a Reminiscence and a Review.” Judaism, vol. 28, no. 4, Sept. 1979, p. 465.