By Alexandra (Sasha) Zborovsky, Arcadia Graduate Fellow

Divided Empires, United Families: The Union of Russian Jews and Post-War Family Reunification across the United States and Soviet Union

Between 1942 and 1949, the Union of Russian Jews and President Samuel Chobrutsky of the Moscow Jewish Community helped over 15,000 Jewish families across the United States, Mandate Palestine, and South America locate and exchange letters with surviving Jewish relatives in the Soviet Union.

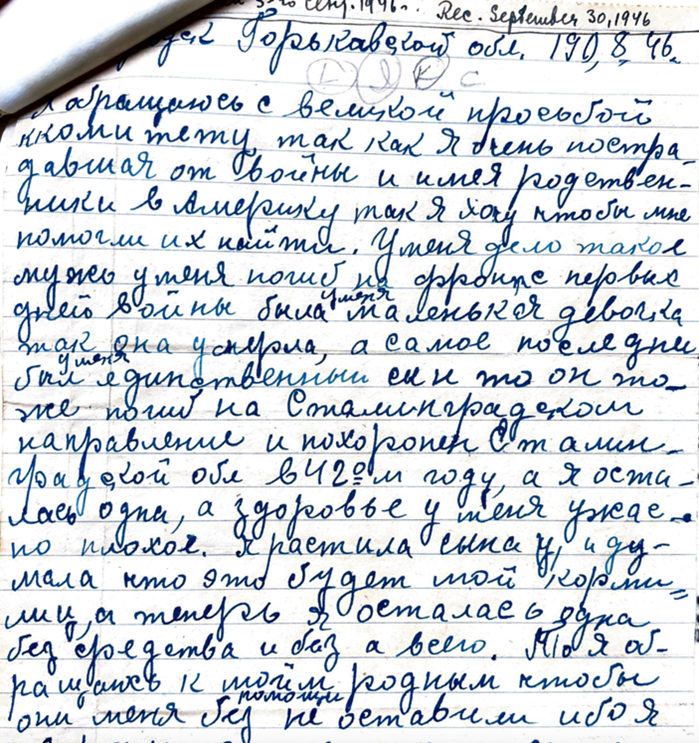

In Fall 1946, Bertha Blumberg of De Ruyter, New York received a highly unusual letter. Writing from the Russian city of Bogorodsk, Bertha’s estranged cousin Asya Verzhbolovskaia painted a gloomy picture. Her children and husband had been murdered in the Holocaust by bullets. “I am left alone,” Asya wrote and must now “turn to my dear relatives so that they may not leave me without assistance.”

Letter from Asya Verzhbolovskaia, RG 270, Folder U-V, Union of Russian Jews. Collection of YIVO Archives.

Asya’s letter to Bertha arrived not in its original Soviet-stamped envelope but on a sturdy sheet translated to English by the Union of Russian Jews. Founded in Berlin as a fraternal organization of liberal Jewish intellectuals fleeing the Russian Revolution, after the rise of Nazism its members eventually relocated to New York. There, the Union of Russian Jews became a formal organization and rededicated itself to educational programming and charity. But as the tides of war turned in the Allies’ favor, the group made an unexpected connection in the Soviet Union: the president of the Moscow Jewish Community.

Thus began the coordinated effort between the Union of Russian Jews in New York City and the President of the Moscow Jewish Community, Samuel Chobrutsky in Tashkent—the site to which many non-military Soviet citizens evacuated during the war. These organizations sought to reconnect Jews in Soviet territory with kin who immigrated to the United States, Palestine, and South America in prior decades. This program was part of Western Europe’s and the USSR’s embrace of family reunification as a form of post-war reconstruction. From a Soviet perspective, reunited families promised to boost the USSR’s birth rate, which the state considered crucial after the loss of over 20 million Soviet citizens in the war. Chobrutsky’s and the Union of Russian Jews’ intentions were different. Likely with the USSR’s emigration and the United States’ immigration restrictions in mind, they resolved to emotionally and economically, as opposed to physically, reunite families. Restored contact with relatives in the West could ease the loneliness and destitution facing Jewish survivors. Indeed, before Soviet forces even entered Berlin, the union boasted the reunion—via post or telegram—of over 6000-7000 families.

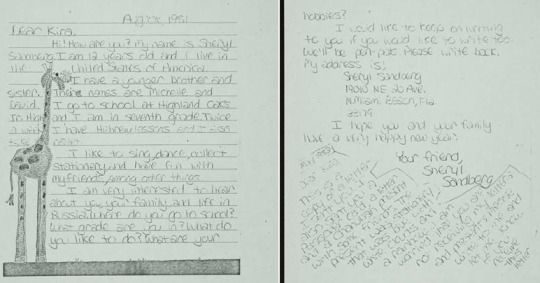

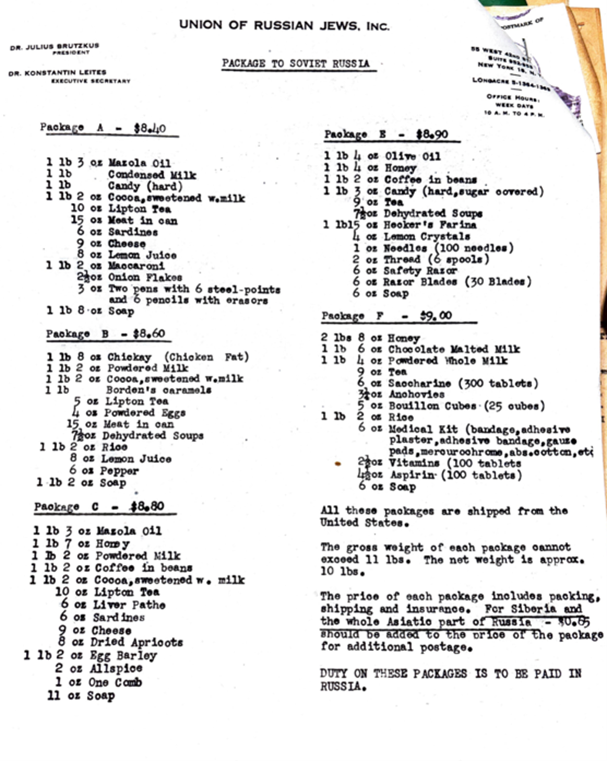

This extensive exchange of letters reflects the impressive organization of and link between two associations—both led by ethnic minorities in their respective states—based in empires already frigidly antagonistic towards one another. Moreover, scholars have long rued the Great Terror’s moratorium on Soviet citizens’ ability to communicate with the outside world and its rollover effect on national minorities—such as Jews—in the immediate post-war era. These letters reveal how throughout the war and immediate postwar era these restrictions were not all encompassing. The Soviet state allowed for a Jewish-specific bureau that located and connected family members abroad. In turn, Soviet Jewish clients displayed an intimate familiarity with the far-ranging familial networks they might have across the globe. They desperately described themselves “as the nieces of [your] sister” or “[your aunt], daughter of Iosif of Proskurov.” They searched for a “sister in Boston” or a “cousin in Montreal” In her aforementioned 1946 letter, Asya listed five relatives that the organization could potentially to trace for her. Almost every single letter writer identifies themselves as the last surviving adult member of a decimated Jewish family and suggests that kin in the United States, Palestine, or South America represents their last remaining support network. In 1947, Ruhel Shinder-Vainer informed her brother that “Germans killed our entire family” leaving Ruhel and her young daughter alone. She revealed than she no longer lived in Illintsi, Ukraine—a town where the majority Jewish population was almost entirely murdered—and had moved to Tulchin, a larger city in the region. She unloaded her loneliness, inability to sustain herself and her daughter, and her displacement. Relatives who received these desperate missives from family members were directly encouraged by the Union of Russian Jews to offer material and emotional support. The organization urged relatives to send the Union of Russian Jews’ pre-assembled food packages. Costing between $7 and $9 these packages included both essentials and quintessentially American products, ranging from powdered milk to macaroni, Mazola oil to Lipton tea. The exchange between participating Soviet Jews and their family members abroad was emotional and material.

As the thinly veiled antisemitism of Stalin’s “anti-cosmopolitan” campaigns impeded Soviet citizens’—and particularly Jews’—communication with the outside world, the Union of Russian Jews found its letters go increasingly unanswered. However, even into 1950 the organization boasted contact with Soviet Jewish families—though letters in the collection rarely date later than 1949. The program’s link to the USSR disappeared shortly after, but not before it had successfully reunited 15,000 families.

Related materials:

Union of Russian Jews (RG 270)

Rachel Wischnitzer Collection (AR 25657): Box 10, Folder 6