By Andrew Sperling, Leon Levy Fellow

The American Nazi Party’s Abduction of a Jewish Boy in 1961

On a humid summer’s night in July 1961, thirteen-year-old Ricky Farber and his friends bounced around their suburban neighborhood in Arlington, Virginia. There, they stumbled upon an odd and frightening house draped in massive Nazi battle flags. What happened next would be a source of contention: Farber and his pals say men appeared suddenly out of the darkness; the men – members of the infamous American Nazi Party – insisted that the boys had pelted their windows with bottles. Within seconds, a gang of neo-Nazis chased the boys down the block. Losing the rest of his group, Farber hurriedly rang doorbells but received no help. Two “stormtroopers” wrangled him violently to the ground and dragged him back to their headquarters.

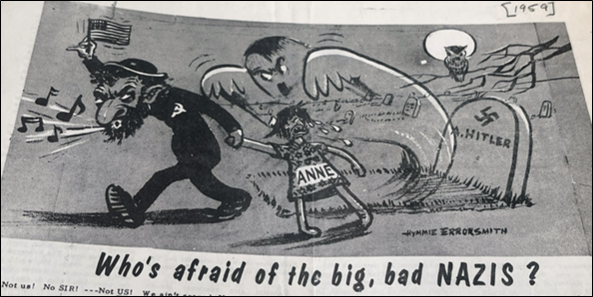

The men were followers of George Lincoln Rockwell, the self-proclaimed “American Fuehrer” who organized the American Nazi Party (ANP) in 1958. Unconcerned with decorum or political correctness, the ANP published lurid antisemitic artwork and propaganda and openly called for the gassing of American Jews. Their headquarters placed them close to the center of American politics in Washington D.C., where they often appeared in Nazi-style uniforms and baited Jewish passersby into fights. Rockwell, the mastermind behind their activities, worked tirelessly to place the group’s name in national headlines. A typical placard or pamphlet distributed on D.C. streets read, “WHITE MAN! ARE YOU GOING TO BE RUN OUT OF YOUR NATION’S CAPITAL WITHOUT A FIGHT?” Like other extremist agitators, Rockwell blamed controversial issues of the day – communism, racial integration – on the Jewish community.

American Nazi Party artwork mocking Anne Frank. American Jewish Committee Records, RG 347.17.12, Box 137. Collection of YIVO Archives.

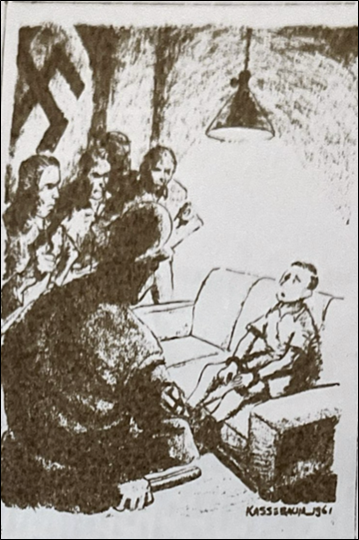

When Rockwell’s admirers captured Ricky Farber, they had one question in mind: “Are you Jewish?” Farber answered affirmatively to which one Nazi shouted, “he’s an integrationist!” Handcuffed and surrounded, Farber was likely too petrified to lie. It was a ghoulish sight: the men interrogated him on chairs turned backwards, flanked by German shepherds with names like “Gaschamber” and “Extermination.” Nooses hung from the ceiling, and naturally, a huge picture of Adolf Hitler dominated the room. Farber endured more questioning until a neighbor, who had witnessed the scuffling outside, alerted police. Once safely in his home, he spent the night pacing and crying hysterically until put to sleep with tranquilizers. Farber’s parents sought a warrant for the arrest of the men who had abducted him – a move that resulted in two assailants serving twelve months in prison for felonious assault, but also subsequent harassment of the Farber family. Unashamed of their actions, the ANP sent the family a stream of antisemitic hate mail.

Robert Kassebaum drew this conception of the Ricky Farber incident, entitled “The Supermen at Work,” which was featured in The Washington Post. American Jewish Committee Records, RG 347.17.12, Box 136. Collection of YIVO Archives.

Rockwell, who was not present during the fiasco, exploited the story and its outcome as evidence of Jewish power and privilege. In a letter distributed to Arlington neighbors, he complained of “hysterical newspaper stories magnifying the accusation – not proven facts – made by the Jewish Mr. Farber,” which he believed would “inflame more ignorant juveniles” to participate in “mob action.” Referring to a number of incidents in which Jewish youths allegedly defaced his headquarters, Rockwell tried his best to convince neighbors that his ANP “does not roam the streets terrorizing ‘children.’ It is the ‘children’ who have tried to terrorize us.” The community – wise to the fact that a cadre of armed, adult men with guard dogs were unlikely to be victims of thirteen-year-olds – remained unsympathetic.

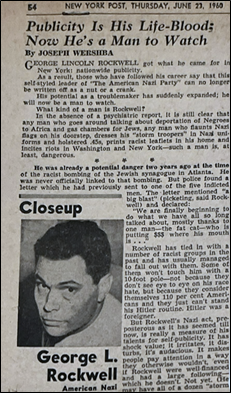

American Jewish Committee Records, RG 347.17.12, Box 135. Collection of YIVO Archives.

Considering the ANP’s house a blight on Arlington, Jewish and Christian leadership brainstormed legal ways to dismantle the group’s presence. They clashed with the local government, which had refused to bring actions against the other Nazis responsible for Farber’s maltreatment and brushed off more serious charges of “abduction” or “kidnapping.” Nazi activity in Arlington continued for years, with civic leaders often debating the meaning of civil liberties. To what extent, they argued, was a violent extremist group protected under the law? Though many Jews believed that even their worst enemies were entitled to freedom of speech and assembly, others pointed to the Farber incident as proof that peaceful co-existence was impossible. These community tensions lingered, with Rockwell and his henchmen remaining the neighborhood “bogeymen” until his assassination by a disgruntled follower in 1967. Episodes like these – often hidden in local newspapers and archival collections like those at the Center for Jewish History – illuminate how antisemitic violence and extreme right-wing terror have appeared even in quaint suburbia.

Related Materials

Records of the American Jewish Committee, Alphabetical Files