By Sarah Nimführ, Visiting Scholar 2025

Islands of Hope and Despair: The Failed Refuge on the Isla de Pinos

On May 13, 1939, the German ocean liner S.S. St. Louis set sail from Hamburg with 937 Jewish refugees on board—among them, Lillian and Georg Friedmann. Fleeing Nazi persecution, they boarded with tourist or transit entry permits purchased from Cuban immigration director Manuel Benítez. Their destination was Havana. But unbeknownst to the passengers and even to Captain Gustav Schröder, their landing permits had already been invalidated by a decree issued days earlier by Cuban President Federico Laredo Bru.

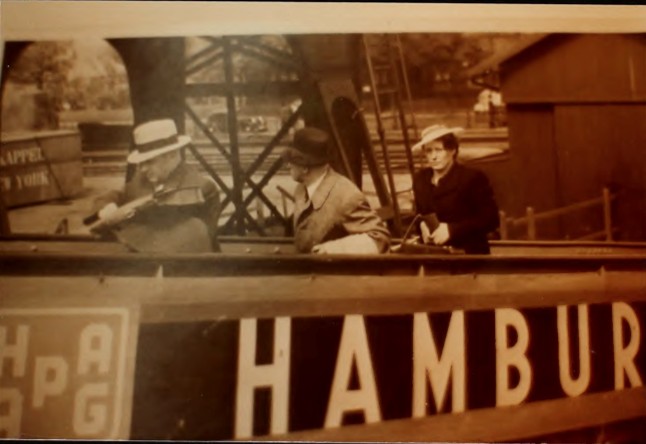

Photo of Lillian and George Friedman boarding the “St. Louis,” May 13, 1939.

George und Lillian Friedman Collection, AR 7223, Folder 1. Collection of Leo Baeck Institute.

It retroactively rendered the permits void, requiring an additional certificate from the Cuban Ministry of Labor and a deposit of 500 dollars. This bureaucratic trap ensured that when the St. Louis reached Havana’s harbor on May 27, most passengers would not be allowed to disembark.

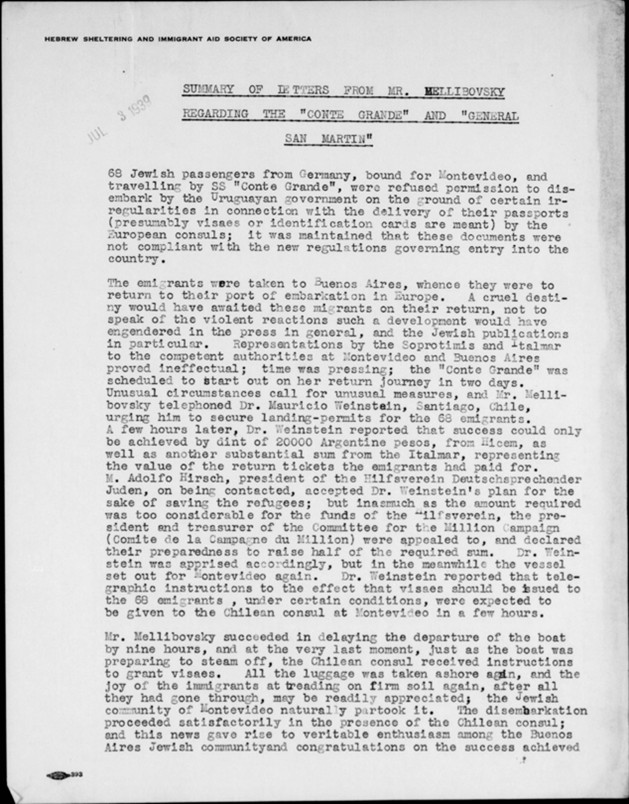

The St. Louis tragedy was not an isolated incident, as I was able to find out from the YIVO Institute’s repository. In the months preceding and following this event, other ships as the Conte Grande or General San Martin – also met rejection at Latin American ports. However, negotiations with the respective countries regarding landing permits were more successful than those of the passengers of St. Louis. These turnarounds reflected a regional hardening of immigration policy driven by anti-Semitic political pressure and media agitation.

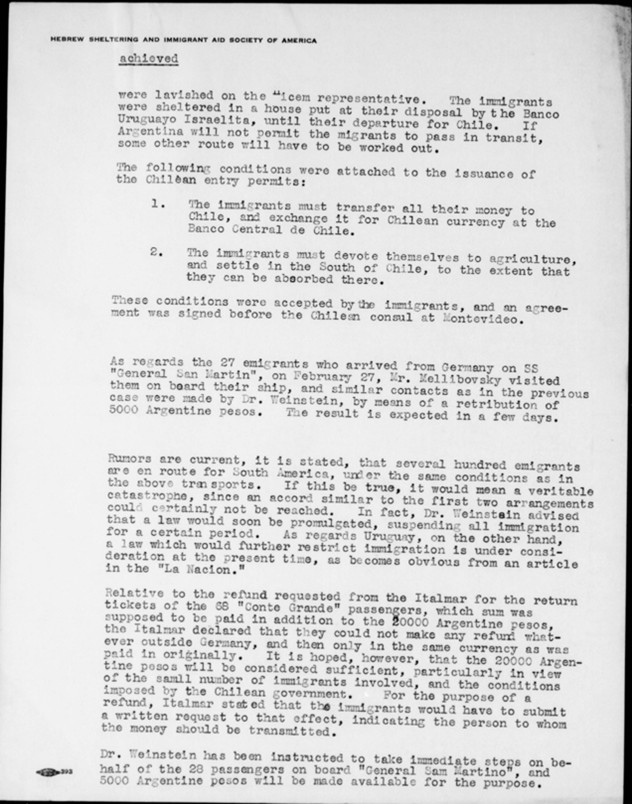

Summary of the letters by Benjamin Mellibovsky regarding the Conte Grande and General San Martin from 3 March 1939, South American representative of the HICEM Central Office.

HIAS & HICEM Main Offices, N.Y. HIAS. RG 245.4.20, Folder 1. Collection of YIVO Archives.

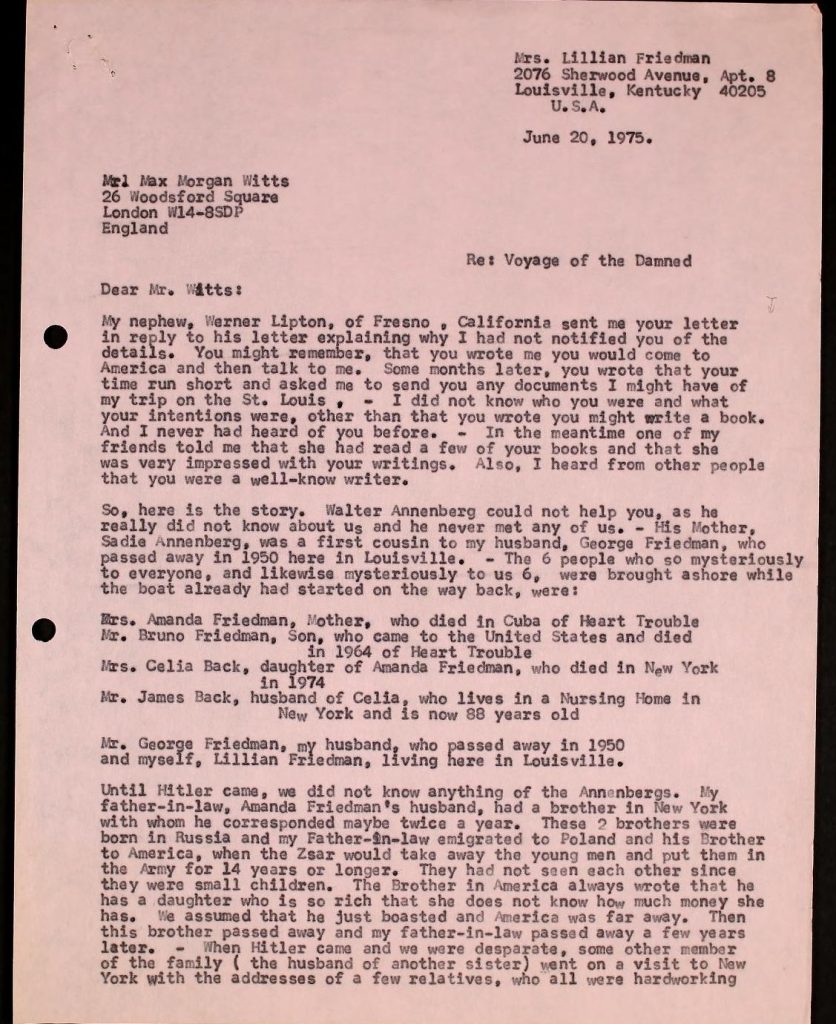

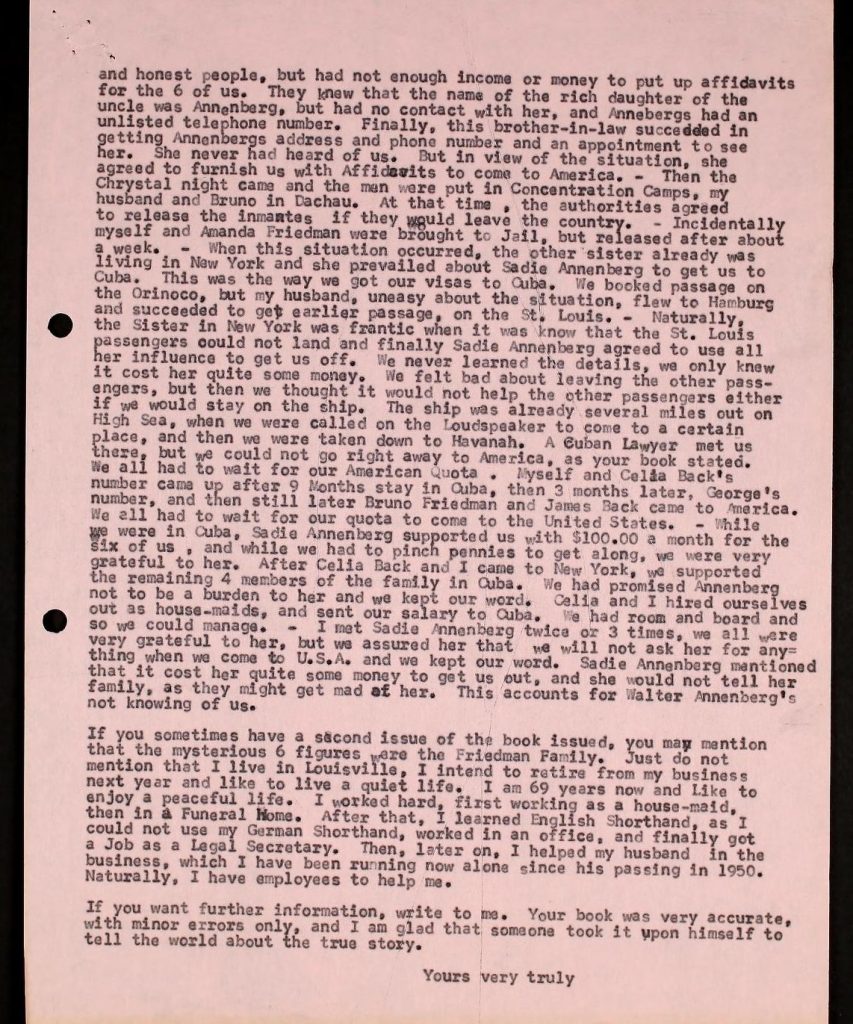

In the case of St. Louis only 22 Jewish refugees were permitted ashore—mainly those who held valid U.S. visas. Lillian and Georg Friedmann were among the fortunate few. In a 1975 letter to author Max Morgan Witts, whose book Voyage of the Damned documented the tragedy, Lillian recounted how they had secured U.S. visas at the last dime thanks to the intervention of Georg’s cousin, Sadie Annenberg. Not only it “costs her quite some money” to get them out, but she also supported them during their months-long wait in Cuba before they continued on to the United States.

Letter from Lillian Friedman to Max Morgan Witts, June 20, 1975.

George und Lillian Friedman Collection, AR 7223, Folder 1. Collection of Leo Baeck Institute.

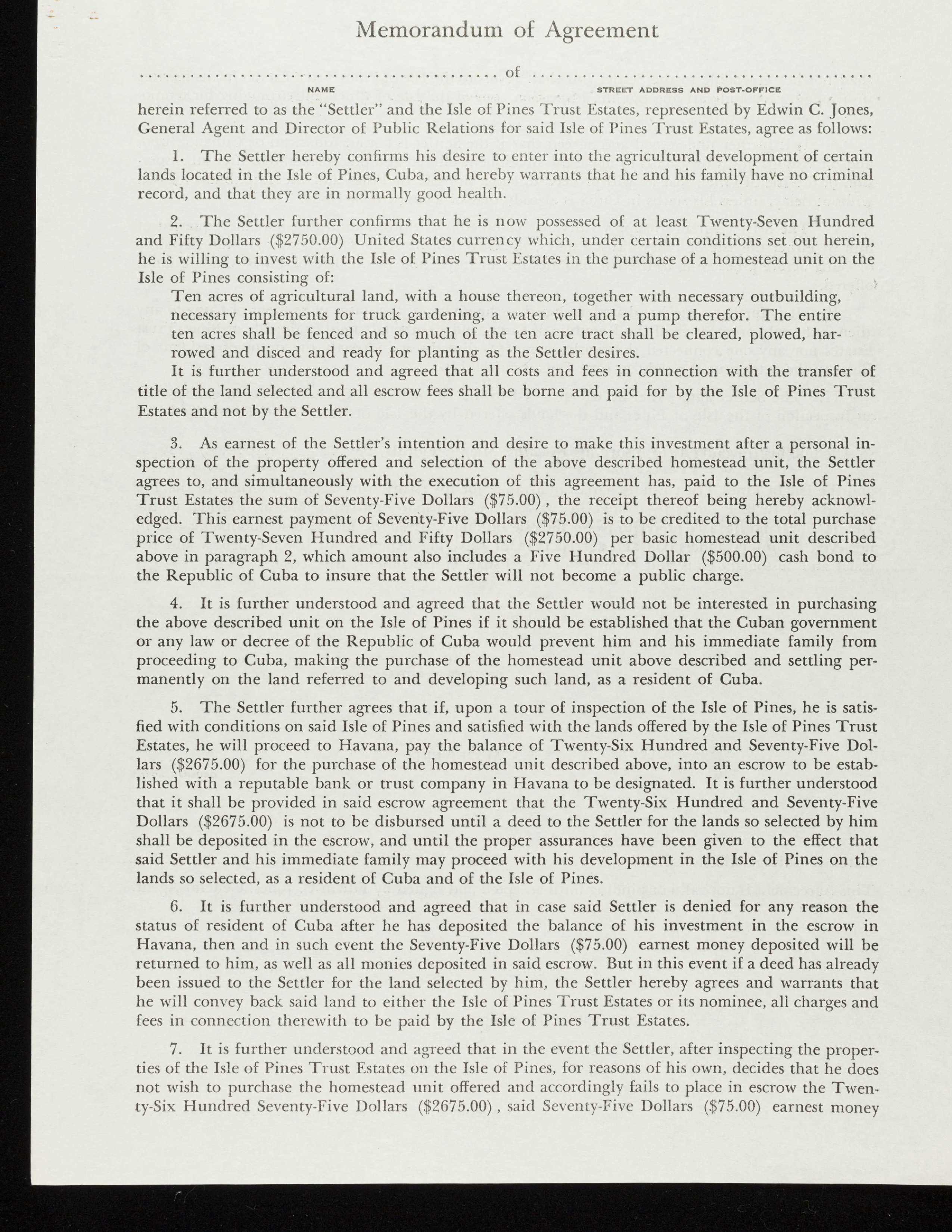

The remaining passengers faced fear and uncertainty. Efforts to find refuge in the United States, Canada, and the Dominican Republic all failed. During my research in the “Sosúa Archives”, I stumbled upon a lesser-known proposal: the creation of an agricultural settlement project for Jewish refugees on Cuba’s Isla de Pinos (now Isla de la Juventud). As an island studies scholar this immediately caught my attention. Since time immemorial, islands have functioned not only as places of longing or everyday life, but also as places of refuge. Isla de Pinos, located about 60 miles southeast of the main Cuban island, was sparsely populated at the time and was able to offer a new life to about 300 Jewish families.

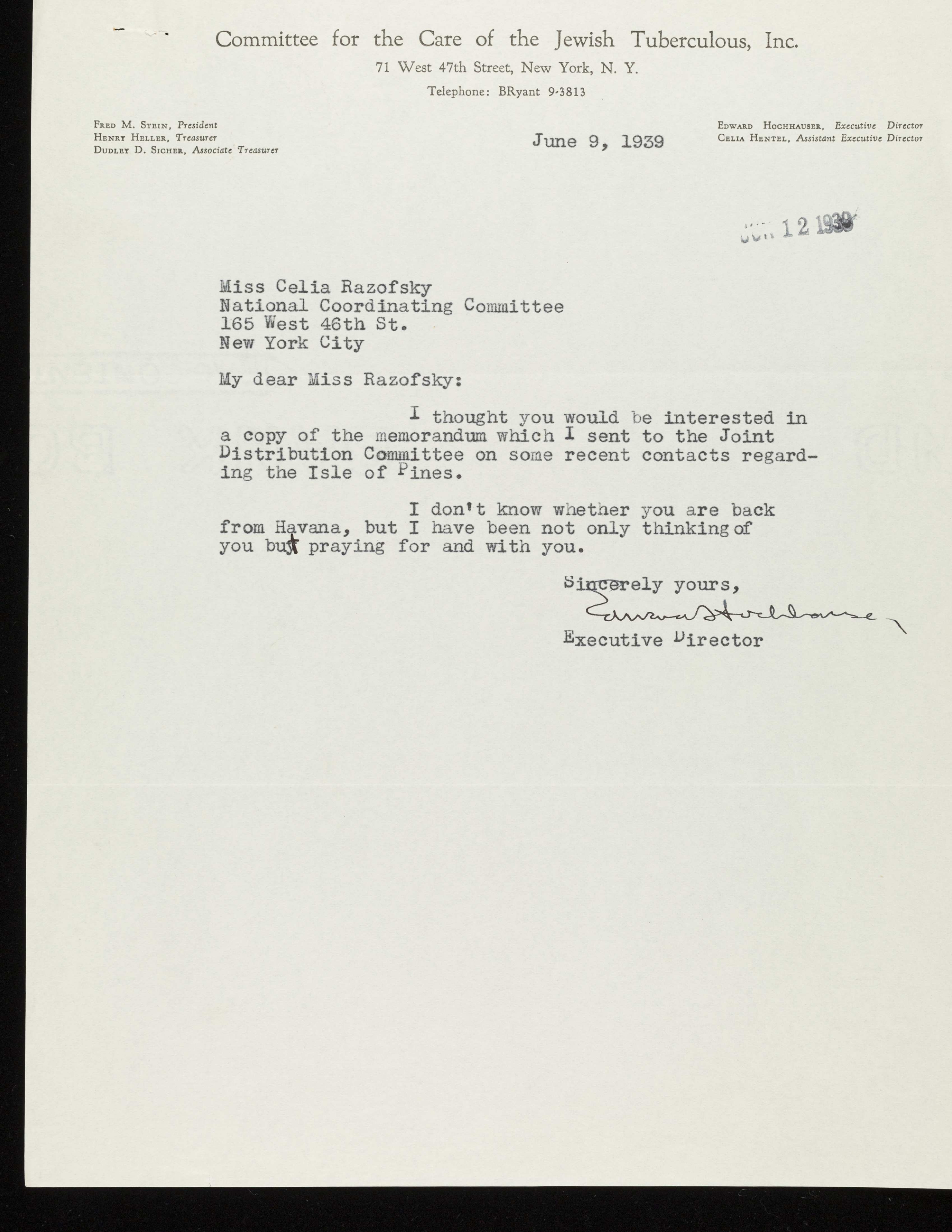

Correspondence between the Committee for the Care of the Jewish Tuberculous and the National Coordinating Committee revealed discussions about a temporary refuge modeled on the Sosúa settlement project in the Dominican Republic, which was decided at the refugee conference in Évian in July 1938.

Papers of Cecilia Razovsky, P-290, Box 4 Folder 6. Collection of the American Jewish Historical Society.

By this time, however, a deadline set by Cuban President Bru had already lapsed. Unaware of this bureaucratic expiration, the negotiating parties’ hopes were soon overtaken by political reality. The St. Louis was ultimately ordered to return to Europe. Eventually, the Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees the Intergovernmental Committee for Refugees managed to get them accepted in England, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Tragically, a third of the former passengers would later perish in the Holocaust.

In contrast to the settlement project in Sosúa, which has left its traces in the Dominican Republic to this day, the Isla de Pinos project was never realized in the years that followed.

Eighty-six years later, these voyages remain a haunting reminder of how borders, bureaucracy, and bigotry can turn a lifesaving ship into political liabilities– and an island into either sanctuary or unattainable utopia.

•••

Related Materials:

George and Lillian Friedman Collection (AR 7223)

HIAS-HICEM Central Offices, New York: Transportation (RG 245.4.20)

Papers of Cecilia Razovsky (P-290)

•••

Sarah Nimführ, Center for Jewish History Visiting Scholar 2025. Sarah is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Arts Linz in Austria and is researching the Jewish diaspora in the Spanish Caribbean.