German-Jewish Americans at Home at the Turn of the Last Century: A Late 19th-Century Photo Album

“. . . the [Jewish) religion which was to be prized and saved is fast becoming a watery Unitarianism, and its adherents are allowing themselves, where permitted, to become completely assimilated. Reform Judaism which began as a compromise is ending as surrender.”

—Marvin Lowenthal, “Zionism: A Menorah Prize Essay [part 1],” Menorah Journal vol. 1:2 (1915): 118-19

Marvin Marx Lowenthal (1890-1969), a leading Jewish writer and lecturer of the early 20th century, wrote his first significant publication on the merits of Zionism. In it, he rejects Reform Judaism as Zionism’s opposite. What is more, he describes the Reform Movement as undermining Judaism itself! And yet, his impressive photo album, generously donated to the American Jewish Historical Society by Sid Lapidus, Board Member of the American Jewish Historical Society and of the Center for Jewish History, illustrates the depth of his German Jewish family’s commitment to the Reform Movement. The album’s recent conservation in the Werner J. and Gisella Levi Cahnman Preservation Laboratory by Book Conservator Lyudmyla Bua has provided us with an opportunity to revisit the question of how this important early Zionist came to terms with his German Reform Movement roots.

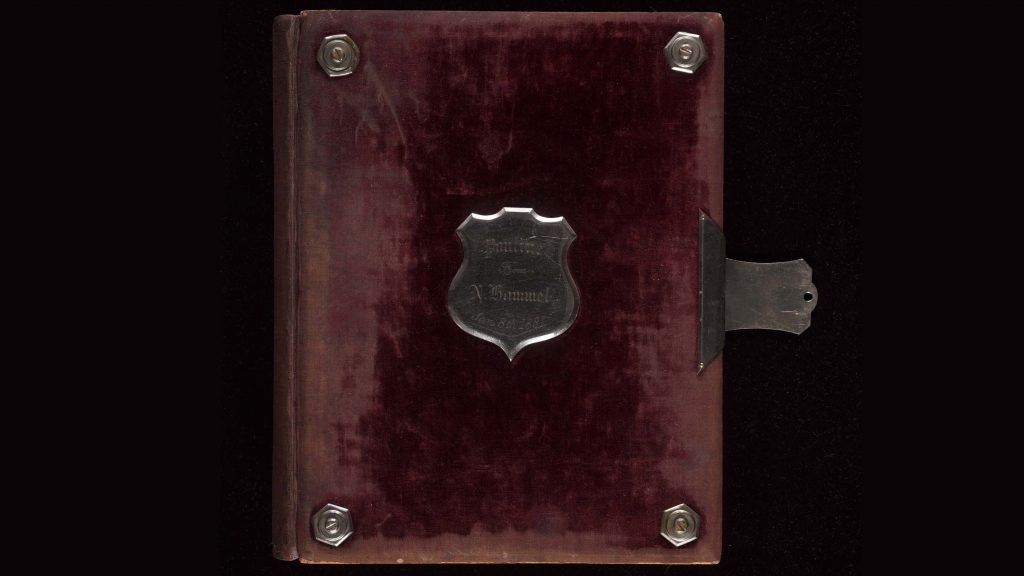

The purple velvet-covered album tells a great deal.

Manufactured and dated 1881, the album was designed for inserting photographs into openings cut out of doubled album leaves. Marvin’s mother, Pauline Marx Lowenthal (ca. 1857-1931), received the album as a gift and filled it to capacity, labeling each photo for Marvin’s benefit. Thirty-seven cabinet cards – the latest type of studio photo – are at the front; the back pages, with smaller openings, are filled with a similar number of old-style cartes de visite and a few tin types. Dating from the early 1870s to the early 1900s, these images were produced up to the moment when the easy accessibility of the Kodak Box Brownie Camera transformed the public’s relationship to photography.

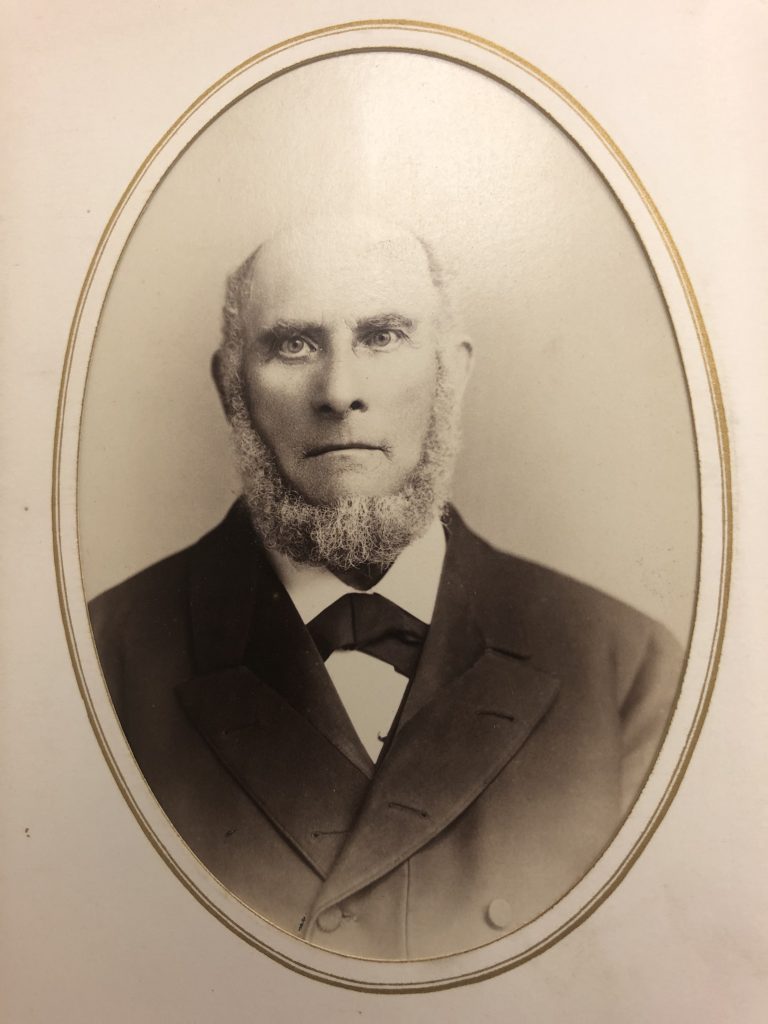

The photos depict family members whose services to the Reform Movement are well-documented. These include a number of first-generation German immigrants, such as a paternal great uncle, Isaac Lowenthal, who served as president of the Temple of Concord, Syracuse, NY, following the presidency of his brother (Marvin’s paternal grandfather Simon, not depicted).[1] Somewhat later, the presidency of his maternal great uncle, Moritz Marx – who had taken in Marvin’s mother when she was orphaned – would extend twenty years, to 1890.[2] Back in Bradford, PA, Marvin’s birthplace, David C. Greenwald, his cousin and close family friend, served as president during construction of a new congregational home; he was still secretary of Temple Beth Zion when Marvin’s “Zionism” essay appeared.[3]

Beyond deep roots in the Reform movement, Marvin’s photo album documents close-knit relations among several families, in particular the Marxes on Marvin’s mother’s side and the Lowenthals on his father’s. By extension, it provides glimpses not only into the still well-established Jewish community of Syracuse, NY, but also into small-town life in Bradford, PA, an oil boomtown, at a moment when its Jewish community was growing.[4] Marvin was related by marriage to Joseph Greenewald, an oil producer who also served as mayor.[5] Marvin’s working life began at the age of 15 in the Bradford silk plant of Henry Leon, a member of Bradford’s Reform community who was active in Pennsylvania’s likewise fast-growing silk industry.[6] The intimacy of relations between Marvin, his extended family, and their social worlds in Bradford and Syracuse is well-documented in the papers of Marvin Lowenthal, also held by the American Jewish Historical Society (archival collection P-140).

In 1912, at 22, Marvin left Bradford for the University of Wisconsin – a university with a growing Jewish student population. Under the auspices of philosophy professor Horace Kallen (1882-1974), the university had just formed a “Menorah Society” on the Harvard model (which Kallen had helped create), to foster a specifically Jewish scholarly community.[7] It was Kallen – who rejected his family’s Orthodoxy just as Marvin rejected his family’s Reform Judaism – who led Marvin towards Zionism as a new Jewish organizing principle. What is more, he led Marvin to the Menorah Journal – the first forum for open intellectual discussion of Judaism – where Marvin was soon serving as both editor and regular contributor.[8]

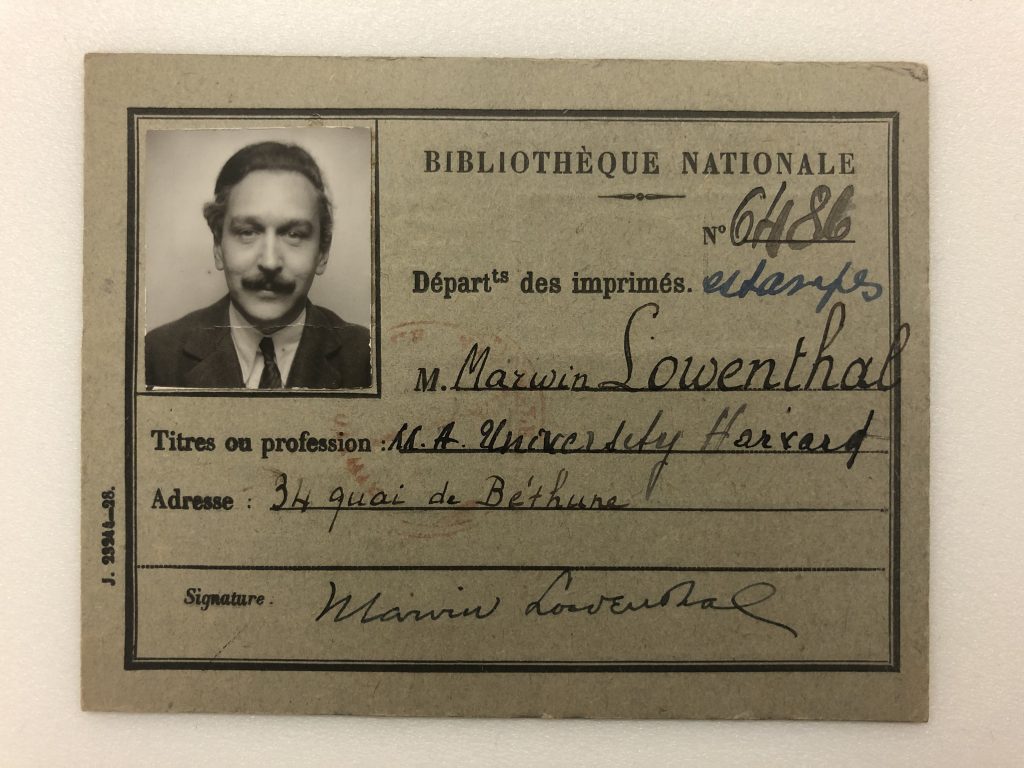

Throughout his life, Marvin Lowenthal would remain true to the Zionism of his early essay. In extensive European travels during the inter-war years, he nevertheless revised his appreciation of the German-Jewish inheritance represented in his album. Building on his travels, in 1936 he published perhaps his most popular work, The Jews of Germany: A Story of Sixteen Centuries. Although he concluded that the time for defining Judaism in terms of its various religious movements had passed, he describes “Reform Judaism [as having] rendered valiant service to German Jewry in its day. . . The controversies it set on foot resulted in a clearer formulation of what all Jews—traditionalists, moderates, radicals, and even non-believers—stood for.”[9] His identification card for research at the Bibliothèque National—dated 1930-31 and inserted loosely into the photo album his mother had filled – attests to his ongoing engagement with the album as he rethought his earlier views of his German-Jewish inheritance.

In addition to the Marvin Lowenthal papers, the album complements other holdings available at the Center for Jewish History, including:

- Marvin Lowenthal’s correspondence with, and writings about, Henrietta Szold: AJHS Archives I-578/RG 13, Executive Functions Records in the Hadassah Archives [esp. Subseries 22: Henrietta Szold]

- Papers of Horace Meyer Kallen (1882-1974), early mentor to Marvin Lowenthal: YIVO Archives RG 317, Horace Meyer Kallen, 1922-1952 [Series V: Correspondence with Individuals, 1906-1952]

For more information about this album and its availability, please contact the American Jewish Historical Society.

-

Jeanne-Marie Musto, Reference Services Librarian, Special Collections