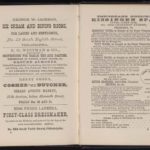

A digitized page from Jewish Cookery Book by Mrs. Esther Levy. Image from the Library of Congress.

Cookbooks of the Collections: An Introduction

by Melanie J. Meyers, M.S., Senior Reference Librarian, Center for Jewish History

The scholarly importance of food studies has exploded as more and more special collections and libraries recognize the value of cookbooks and other such items. Scholars in a multitude of disciplines—history, women’s studies and marketing/advertising, to name a few—can use cookbooks to examine cultural trends and other societal nuances. By and large, cookbooks and other works explaining domestic economy are written for women, so they are often illuminating in discussions of women’s roles within the family and in society. For the Jewish woman in particular, cookbooks are valuable resources in examining her unique relationships to home and family, and her roles within domestic and religious contexts.

The five partner organizations here at the Center for Jewish History hold at least 500 cookbooks in total. Cookbooks are represented in every collection, and in both library and archival collections. If looked at en masse, they provide an astonishing view of the broad spectrum of Jewish domestic lives over three centuries and across multiple continents, and they represent dozens of different regional experiences.

The earliest cookbook housed at the Center is from the collection of The Library of the Leo Baeck Institute. It dates back to 1823. Entitled Vollstaendige Anweisung zur Kunstbaeckerei (Erfurt : Keysersche Buchhandlung, 1823), it was written as “complete instruction for the art baker’s shop,” which appears to denote a specialty bakery shop. Its author was a man named Johann Eupel, and he wrote it for professional bakers in 19th-century Germany. Though the vast majority of cookbooks were written by women and intended for a female audience, professional bakers in Eupel’s time were almost exclusively male, as baking was considered a skilled profession. The book contains recipes for all manner of cakes, pies, cookies and beverages, as well as helpful hints for running a store.

In 1861, the venerable Mrs. Beeton’s treatise on household management was published in England, to great success. Her book on domestic economy and diligent housekeeping became the standard reference book for every middle- to upper-class Victorian housewife who ever wondered how to plan a menu, manage her servants or set a table in the appropriate manner. The Jewish community created some “Mrs. Beeton’s” of their own, tailoring their books on housewifery to fit the Jewish middle-class experience.

In 1871, Mrs. Esther Levy authored the first Jewish cookbook to be printed in the United States, a lovely copy of which is held by the Library of the American Jewish Historical Society here at the Center. Simply titled Jewish Cookery Book (Philadelphia : W. S. Turner, c1871), the work discusses everything the Jewish housewife needs to know—specifically, the “principles of economy…adapted for Jewish housekeepers.” The book contains kosher recipes for meat, fowl, fish and vegetables; a month-to-month list of what foods to buy according to the season to guarantee the best flavor and freshness; sample menus for everyday use and holiday entertaining; a list of recommended supplies and utensils for the kitchen; and a calendar of Jewish holidays and festivals. Mrs. Levy also included a section on household tips such as how to rid one’s home of vermin, how to make homemade shoe blacking and how to best clean carpets.

Frau Joseph Gumprich of Germany authored her own book on cookery and housewifery in 1888, entitled Vollstaendiges Praktisches Kochbuch fuer die Juedische Kueche,or, The Complete Practical Cookbook for the Jewish Kitchen (Trier: Im Selbstverlage der Verfasserin, 1888), a copy of which is held by the Library of the Leo Baeck Institute. In the same vein as the books by Mrs. Beeton and Mrs. Levy, Frau Gumprich’s book discusses recipes, menu planning, and the importance of a well-run household and kosher kitchen. The book was published in several successive editions, with the ninth and final edition published in 1925. In 2002, it was republished in a facsimile edition for a modern audience, using its second edition (published in 1896) as a source, as no copy of the first edition could be found prior to publication. However, the copy held by The Library of Leo Baeck Institute was published in 1888, so it is one of the first editions.

Check back for the next installment of this series to read about the regional flavors of the Jewish cookbook. And don’t forget that you can search the collections by clicking here.