By Lauren Gilbert

Director of Public Services, Center for Jewish History

Death Masks at the Center for Jewish History

Death masks, molded from plaster in the first hours after death before the features have stiffened or atrophied, were used for centuries to preserve the appearance of nobility and other eminent persons as models for posthumous sculptures or painted portraits. In the 19th century, these unnervingly accurate impressions came to be prized in their own right, and the practice of creating death masks as mementos spread to middle and upper-middle class families.

To create a death mask, thin layers of plaster bandages were applied to the face and head of the deceased, which was oiled or greased to allow easier removal. After it was lifted off in two or more pieces and reassembled, this cast would create a mold into which wet plaster, wax, or bronze could be poured to create a positive image. The original mold could be reused multiple times.

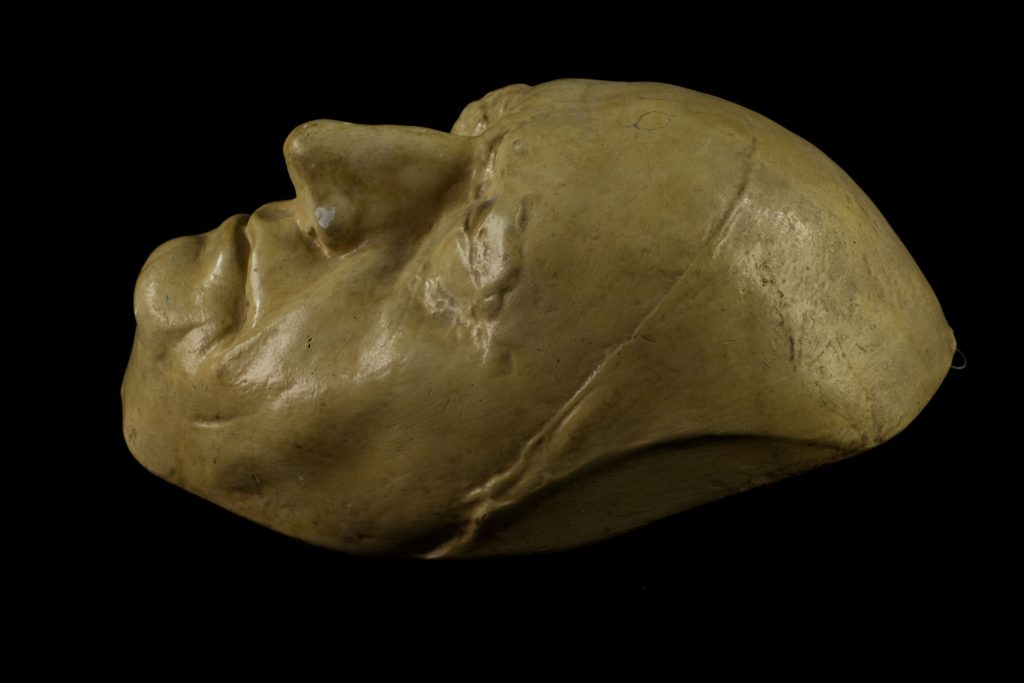

The collections of the partner organizations at the Center for Jewish History contain several examples of death masks. Most of these are likenesses of prominent Jews, but not all; the 1832 death mask of the revered German writer Johann Wolfgang Goethe [below] entered the collections of the Leo Baeck Institute with a donation of archival materials from German-Jewish author and historian Johannes Urzidil (1896-1970).

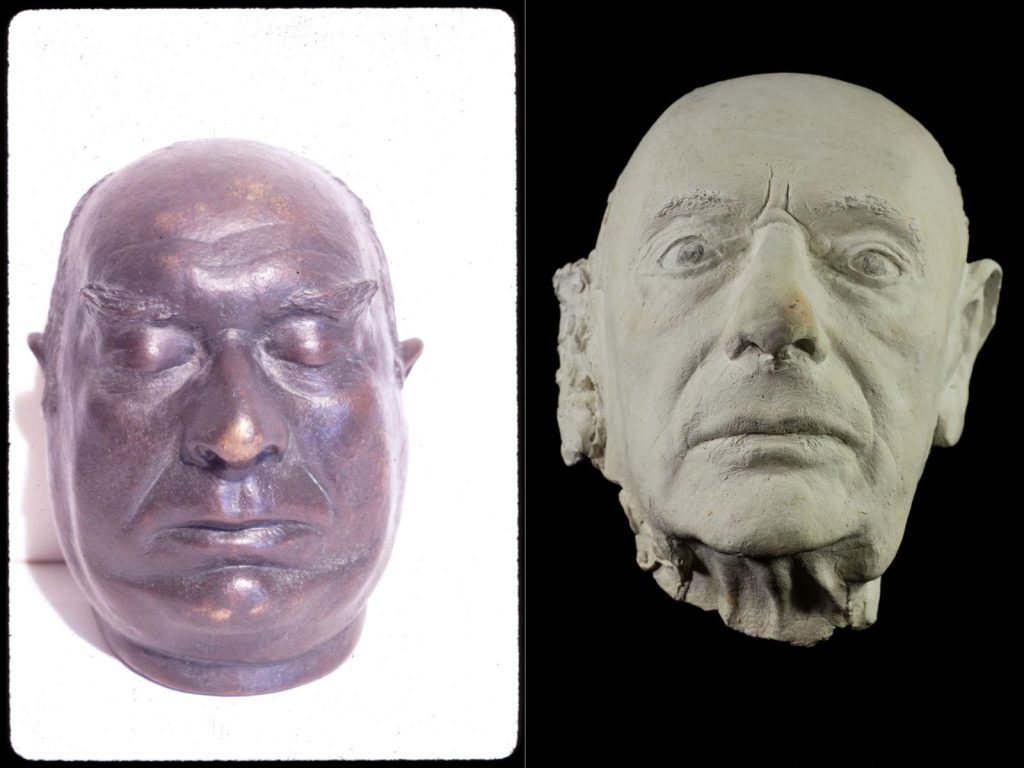

Interestingly, the Leo Baeck Institute also owns Urzidil’s own bronze death mask from 1970 [below left]. Though the popularity of death masks decreased with the advent of photography, there are examples from well into the 20th century. The most recent death mask in the collections is a 1982 mask of Gershom Scholem [below right], a German-born Israeli philosopher, historian, and librarian who was instrumental in spreading awareness of Jewish mysticism and Kabbalah. Unusually, Scholem’s eyelids are open, and eyes have been drawn on the plaster.

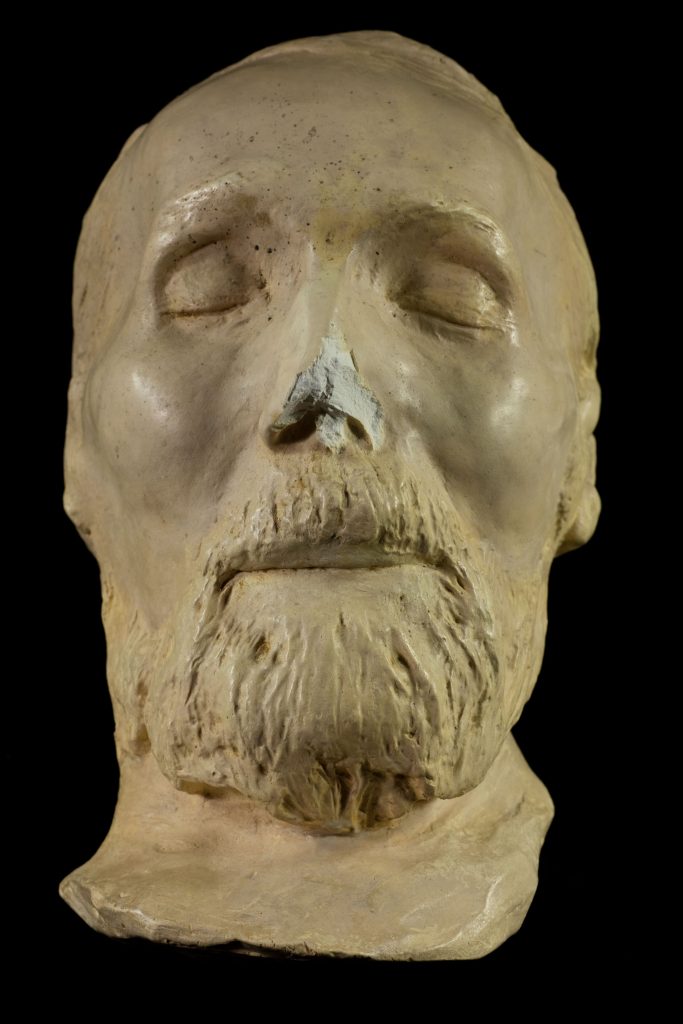

Also found in the collections of the Leo Baeck Institute is the 1856 death mask of celebrated German poet Heinrich Heine [below], who was born into a Jewish family in 1797, though he converted to Lutheranism in 1825, an act that he called “the ticket of admission into European culture.”

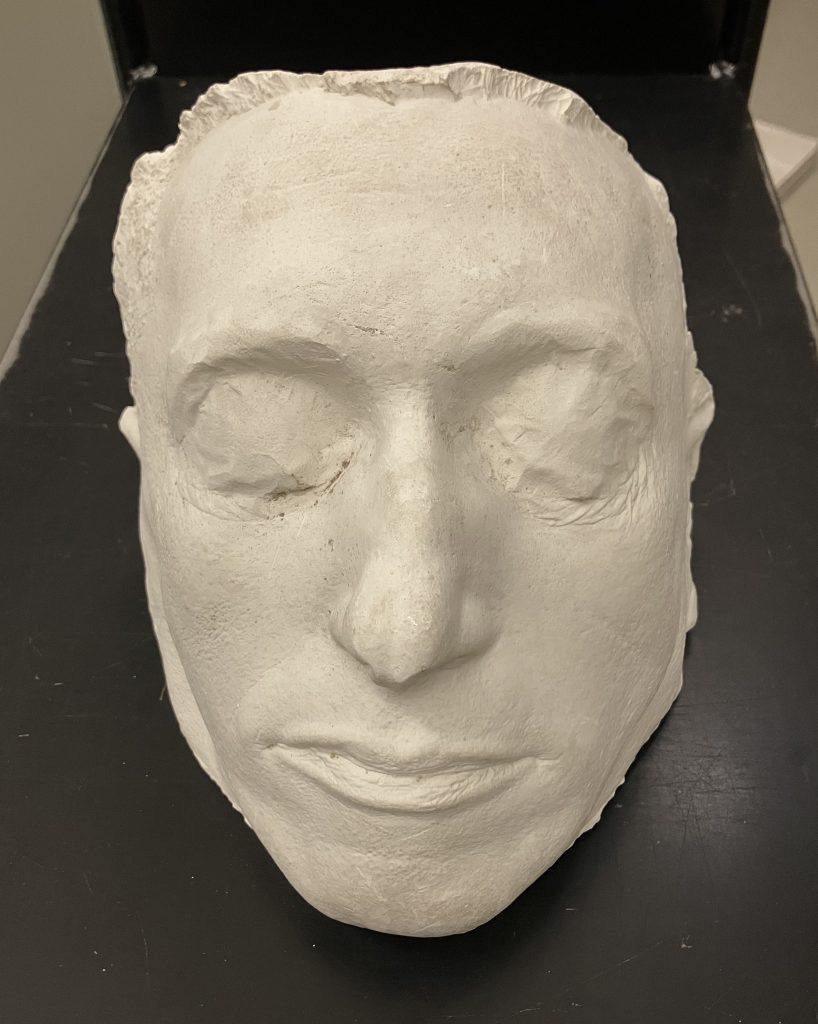

YIVO owns the death masks of several Yiddish writers, including Solomon Blumgarten (1872-1927), better known by his pen name Yehoash, a renowned poet and scholar [below]. Among his many achievements, Yehoash translated the entire Old Testament from Hebrew into Yiddish.

Also in YIVO’s collection is the death mask of Baruch Charney Vladeck (1886-1938), who was an activist in the Jewish Labor Bund in Minsk before immigrating to New York, where he became a labor leader, manager of The Jewish Daily Forward, and a member of the New York City Council representing the American Labor Party. His Lower East Side funeral procession in 1938 drew over 500,000 mourners.

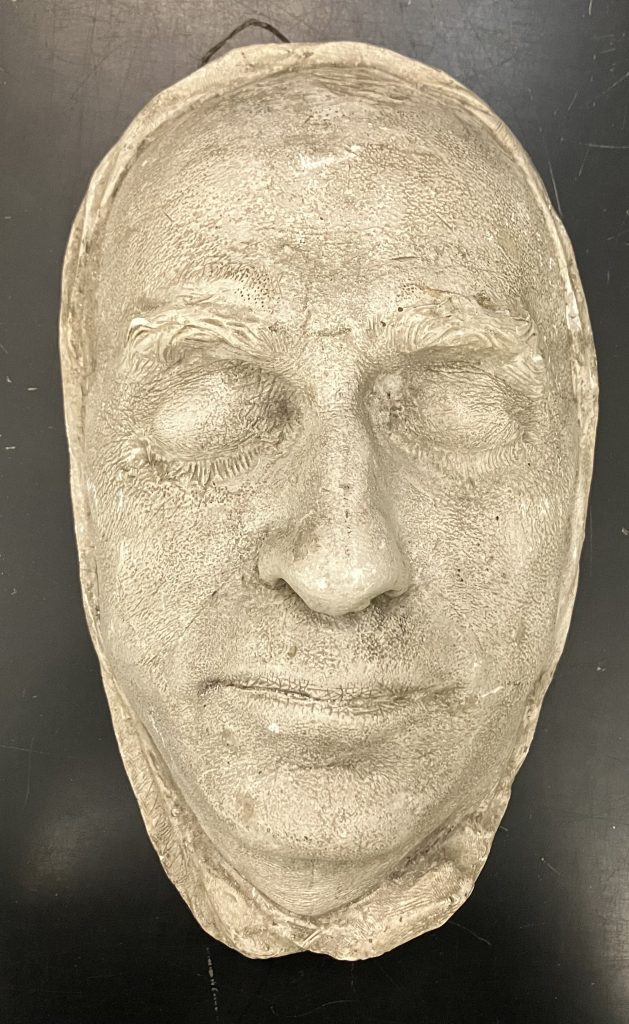

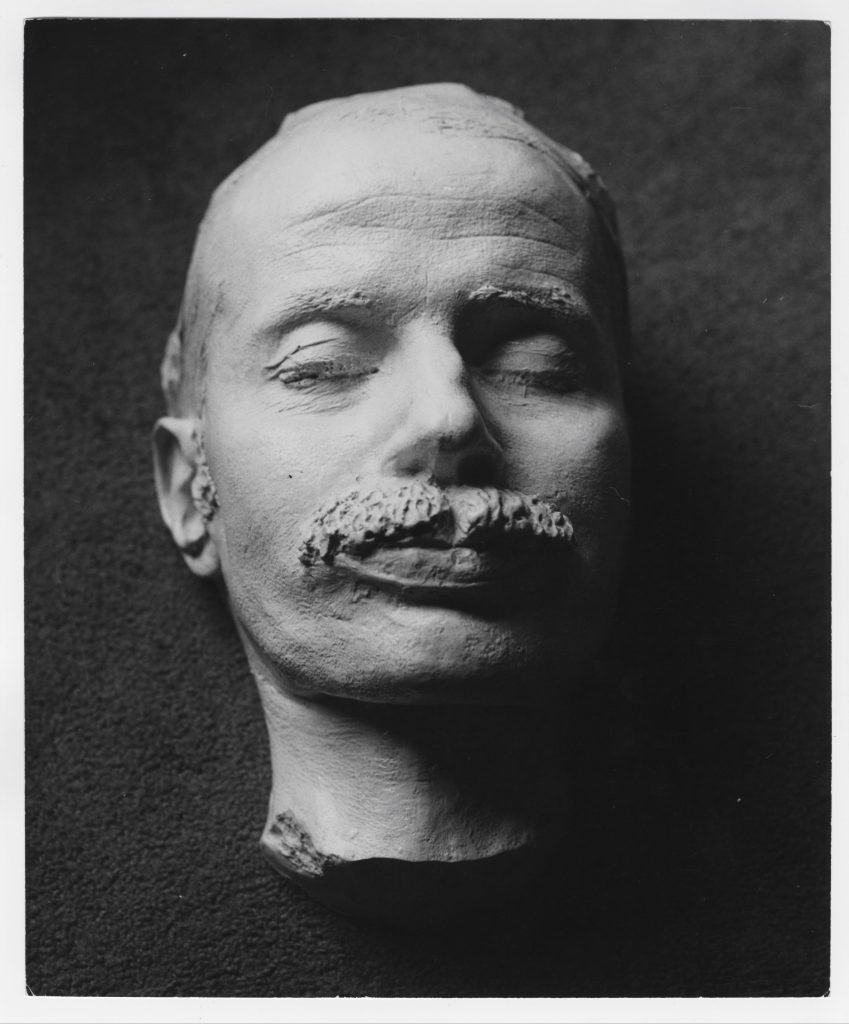

Found at the Leo Baeck Institute, the 1915 death mask of Paul Erlich [below], a Nobel Prize-winning German-Jewish physician and scientist, contains a remarkable level of detail in the facial hair and eyelashes. Among Erlich’s many notable contributions was finding a cure for syphilis in 1909.

The Leo Baeck Institute also owns the strikingly faithful 1929 death mask of Franz Rosenzweig, a German-Jewish philosopher and theologian who died of ALS at the age of 43. Raised in a secular household, Rosenzweig entertained the idea of converting to Christianity, though a mystical experience after a Yom Kippur service at a Berlin synagogue led him to rededicate himself to Jewish religious observance.

Not surprisingly, given the societal standards of the time, men were far more likely than women to be considered sufficiently “notable” subjects for death masks. However, there are at least two death masks of women found in the partner collections at the Center, including one of German-Jewish poet, philosopher, and critic Margarete Susman (1872-1966), who spent much of her life in Switzerland [below].

The American Jewish Historical Society holds the death mask of Henrietta Szold (1860-1945), the founder of Hadassah, among the myriad artifacts in the extensive Hadassah Archives on Long-term Deposit [not pictured]. Under Szold’s leadership and direction, Hadassah, the women’s Zionist organization, became the largest and most powerful Zionist group in the United States. Her efforts enabled the creation of hospitals, nursing schools, food banks, and social work programs, including Youth Aliyah in the 1930s, which helped Jewish children escape Nazi Germany.

While today we might find the practice of making and displaying death masks macabre or creepy, the examples shown here were created as tributes to illustrious figures and revered as such. There is however an undeniable undercurrent of the “memento mori,” a reminder of the inevitability of death, even for the greatest among us.

In addition to archives, manuscripts, and printed materials, the partner collections at the Center for Jewish History contain a wide array of art, objects, and artifacts. You can search the collections using our shared catalog. If you need assistance, contact a librarian at inquiries@cjh.org.

A fascinating(if eccentric) tribute to these illustrious individuals.

Beautiful imagery and stories.

There was never a death mask from Goethe’s face. What you own is his life-mask!