We’re honoring National Preservation Week (April 26 through May 3) with a series of posts from our archival experts about the best way to take care of your precious artifacts at home. From April 29 to April 30, we’re also holding free events at the Center. Come by to learn more in person!

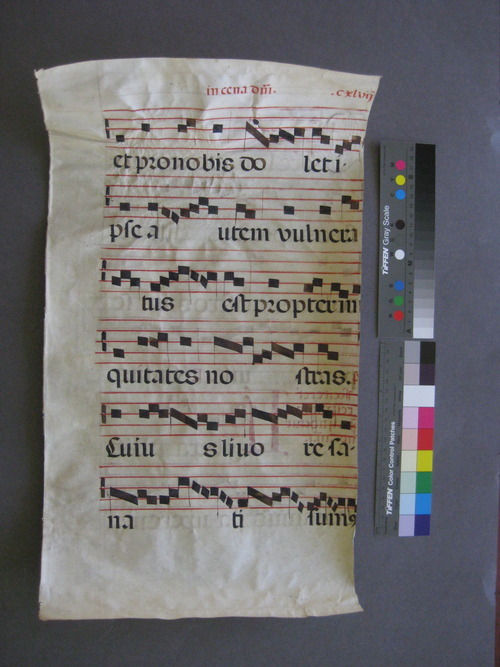

Above: Parchment that’s cockled, or distorted, due to humidity.

by Felicity Corkill, Associate Conservator, Center for Jewish History

The preservation of collection materials has some formidable adversaries. Climate, light, pollution and pests are all crucial factors in what we call the preservation environment. Fortunately, there are remedies that conservators—both trained and self-taught—can deploy when something does go awry.

Of the factors above, the most influential is climate—specifically, temperature and relative humidity. Every material will decay over time, and the temperature and relative humidity in an artifact’s surrounding environment will greatly influence its rate of deterioration.

Above: A bark painting cracked due to excess dryness.

In general, it’s best to maintain lower temperatures and drier conditions. Scientists will know that the rate of chemical reaction (decay) increases with higher temperatures and more moisture. But freezing temperatures and arid conditions will also cause damage. A happy medium for storing heritage items is between 40-70F and 35-55% relative humidity. However, it is also preferable for the climate not to fluctuate too wildly, within even these parameters.

Most of us are (unfortunately) familiar with the scenario of precious items getting first wet and then moldy. Recently, during routine collection inspections at the Center, we discovered that a water leak had gotten to a group of books on a shelf. As the books had been wet for a few weeks, mold had already set in. It takes only 48 hours for mold to begin growing on wet items stored at room temperature, and much less time if the environment is hot.

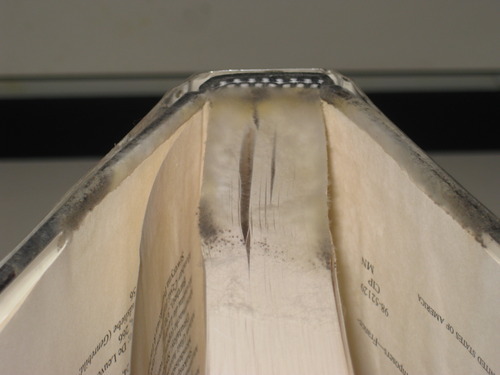

Above: Mold overtaking a book.

Mold not only destroys organic materials, digesting them as the colony grows, but is also very toxic to people. Everyone handling these books in hopes of reversing the damage wore gloves, clothing covers, particulate masks and protective glasses. While the leak was being checked and the shelving cleaned, the affected books waited in a sealed box to isolate them from the rest of the collection.

To dry them, we fanned them open in a secure area—one with airflow but no danger of mold spores blowing into other collection areas. Once the books were dry, our team cleaned them with a brush and a low-suction HEPA filter vacuum.

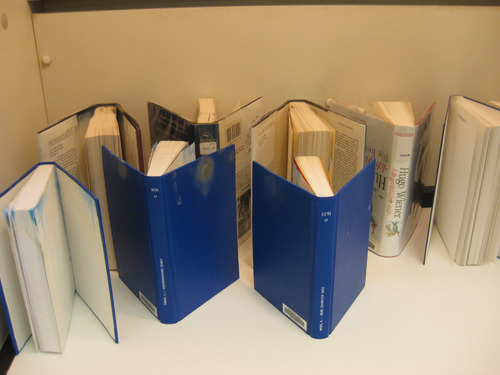

Above: Drying wet books in a safe area.

It’s important to know how to come to the rescue of a valuable artifact (and your health) if any of the above scenarios do occur. Even better, do everything you can to prevent them in the first place. To preserve your own books and other heritage materials, remember these core principles:

• Avoid storing collections in attics and basements.

• Check boxes in storage and artworks on the wall every six months to make sure they aren’t wet and don’t have insect infestations.

• Never display photographs or artworks in direct sunlight.

More posts in our National Preservation Week series:

Your Digital Family Album: A System for Safekeeping

Start Making Sense: Ordering the Chaos of AV Material

For Delicate Books, Safe and Snug Houses

Organizing Digital Files: Getting Your Photos and Scans in Shape