By

Poorvi Bellur

Conducted

over the course of Black History Month 2017, this research project is

structured around primary sources from the archives and the personal

collections of each of these individuals and their correspondences with other

important leaders of the Civil Rights movement. This study focuses on the

umbrella organization of the American Jewish Congress and profiles 3 major

voices in the Jewish fight for Civil Rights: Shad Polier, Justine Wise Polier

and Will Maslow.

Introduction

“The

problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line”WEB Dubois

I am a current undergraduate student at

Columbia University in the City of New York studying postcolonial history and political

science. From January to April of this year, I worked as an intern at the

Center for Jewish History, as part of the Kenneth Cole Community Action

Program. Specifically focused on the region of the Middle East and South Asia,

I am interested in the imperial legacies in the postcolonial world order,

especially surrounding lines of race and caste. Recent coursework led me to

become interested in questions of American democracy and race, especially those

concerning minority interactions and systems of privilege in legislation. With

these topics in mind, I decided to dedicate my time at the Center to studying

the history of African American-Jewish relations, particularly during the

post-World War II Civil Rights Movement.

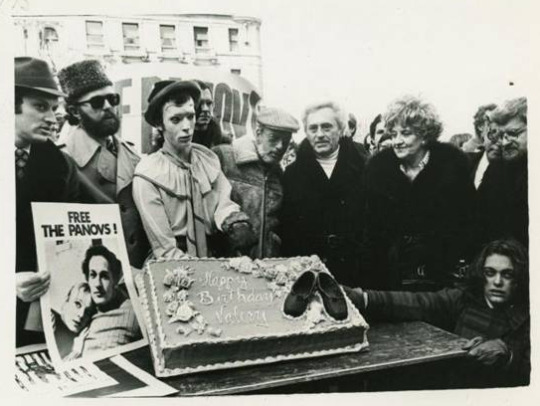

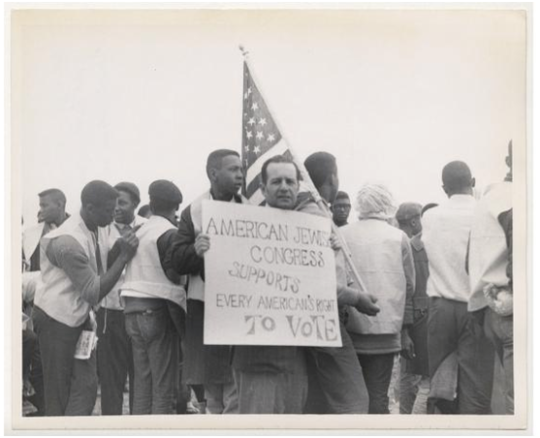

Members of the AJC holding up a sign at Montgomery March (American Jewish Historical Society, American Jewish Congress records, undated, 1916-2006, Call #I-77, Box 744, Folder 41)

This push against racism – punctuated by a

series of revolutionary legislative acts and public demonstrations – revealed

an extremely complex relationship between the black and Jewish communities,

united and divided at different times and by different degrees. This complexity is in part a legacy of the

history of black and Jewish interactions in the United States. Since even

before the Civil War period, groups of American Jews protested and openly

opposed the practice of slavery, and discrimination against African Americans.

Indeed, the Scottsboro case of 1931, one of the most high profile cases of

racial discrimination in the legal system, when nine African American teenagers

falsely accused of raping two white women on a train in Alabama and jailed,

with an all white jury condemning the group of young boys to death, Jewish

lawyer Samuel Leibowitz assumed the case without pay. He claimed to be inspired[1] by

the case of Leo Frank, a Jew in Georgia falsely accused for murder and lynched,

demonstrating the sympathy that many American Jews felt for the plight of black

Americans. However, other

groups, who sought assimilation in order to avoid provoking anti-Semitism,

denied such solidarity with the marginalized black community. The

archives of the Center’s partners house a plethora of sources revealing the

intricacies of these interactions and the impact they had on the movement at

large.

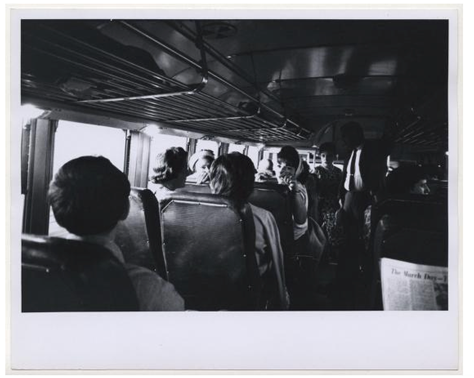

Members of the American Jewish Congress on the chartered bus on their way to March on Washington

(American Jewish Historical Society, American Jewish Congress records, undated, 1916-2006, Call #I-77, Box 743, Folder 26)

This study specifically focuses on the activities

of the umbrella organization, the American Jewish Congress – whose archives are

held by the American Jewish Historical Society (AJHS). I was particularly

interested in this organization because, as opposed to other Jewish social

activist collectives at the time which focused on more passive educational reform,

the AJC prioritized radical social legislative reform. Initially one of many

Zionist organization and led by Stephen S Wise, the AJC came to broaden its

scope and become the beacon for Jewish voices supporting legal reform in

America to combat systemic racism. Wise was also a founder of the NAACP and the

ACLU, and was known for his emphasis on the spirit of pluralism and under his

guidance the “AJCongress articulated the view that group, and not individual,

interests needed to be advanced through appropriate organizational channels and

not merely through a few well connected individuals”[2].

By 1945 the broadened focus of the

organization moved to strengthen American democracy through social legislation

reform and the Commission on Law and Social Action was set up to fight

discriminatory practices by big institutions and corporations alongside groups

like the NAACP and ACLU. What set the AJC apart from was that it over quiet

educational programs of other organizations such as the American Jewish

Committee. The AJC of the 1930’s onwards could be characterized as the social

rights lawyer of the American Jewish Community with its focus on First

Amendment cases and civil rights. Through three upcoming blog posts, I will

demonstrate the thrust of these activities through the lives of three of AJC’s

major figures – Shad Polier, Justine Polier and William Maslow. Conducted over

the course of Black History Month 2017, this research project is structured

around primary sources from the archives and the personal collections of each

of these individuals and their correspondences with other important leaders of

the Civil Rights movement.

[1] Norwood, Stephen H., and Eunice G. Pollack. Encyclopedia

of American Jewish history. Vol. 1. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2008.

Print.

[2] Jerome A Chanes-Norwood, Stephen H., and Eunice G.

Pollack. Encyclopedia of American Jewish history. Vol. 2. Santa Barbara, CA:

ABC-CLIO, 2008. Print.