By Lauren Gilbert (co-curator)

Senior Manager for Public Services, Center for Jewish History

An Unlikely Journalist: Emile Bocian in Chinatown, Part 2

A NEIGHBORHOOD IN TRANSITION

This is a series of blog posts about the upcoming exhibition An Unlikely Photojournalist: Emile Bocian in Chinatown, a joint project of The Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA) and Center for Jewish History. For an overview of the exhibition and its origins, read this post first.

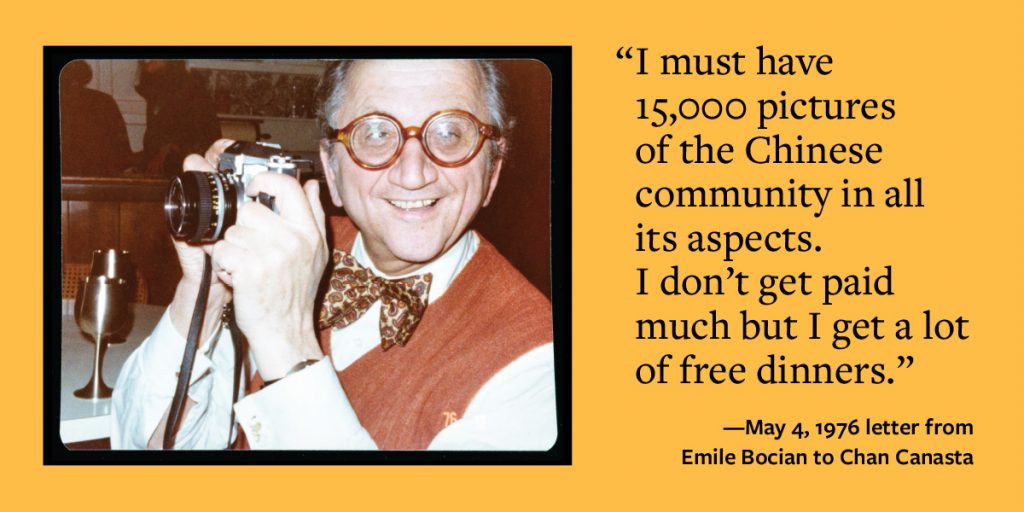

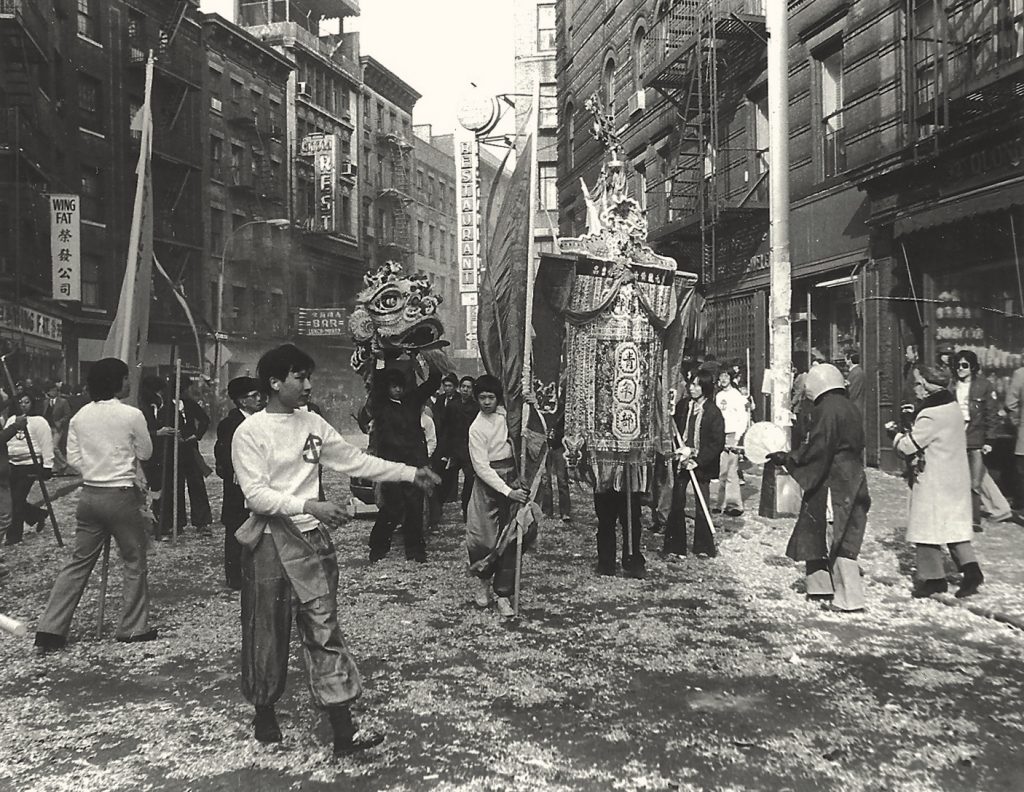

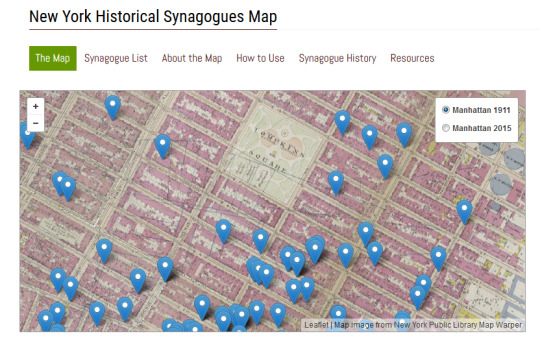

Emile Bocian (1912-1990), son of Eastern-European Jewish immigrants, photographed Chinatown from 1974 to 1986, a period of extreme transition for the community. He used to tell his friend Mae Wong, who rescued his photo archive from his apartment after his death and donated it to MOCA, that he was taking pictures of the streets of Chinatown because he thought they would be a valuable reference, and he hoped to return in the future to document the changes. Though he was unable to complete that task in his lifetime, CJH art director Shayna Marchese returned to photograph selected sites earlier this year for this exhibition.

As one of the last neighborhoods in Manhattan to undergo gentrification, Chinatown still boasts many of its original structures, in some cases even housing the same business as in Bocian’s day, such as the Hop Shing Restaurant at 9 Chatham Square. (below)

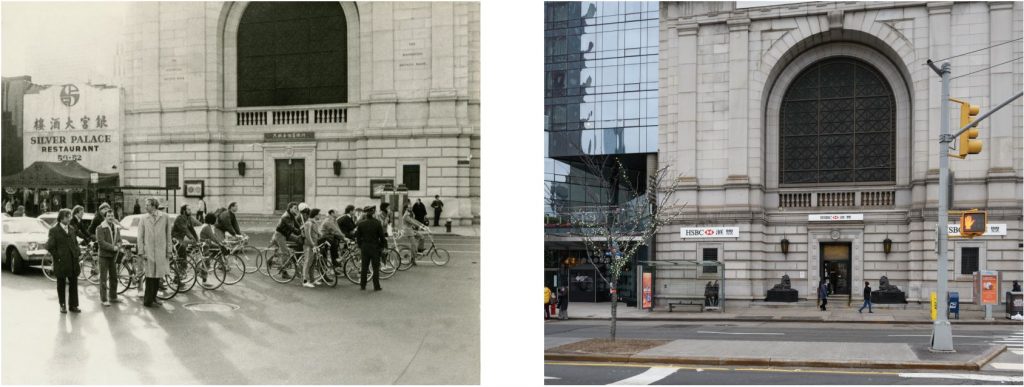

However, over the past 15 to 20 years, several structures have been torn down or renovated into upscale apartments, hotels, or offices, as evidenced by the replacement of the Silver Palace Restaurant (next to the Manhattan Savings Bank) by the modern glass high-rise “Hotel 50 Bowery,” once the site of a Yiddish vaudeville theater. (below)

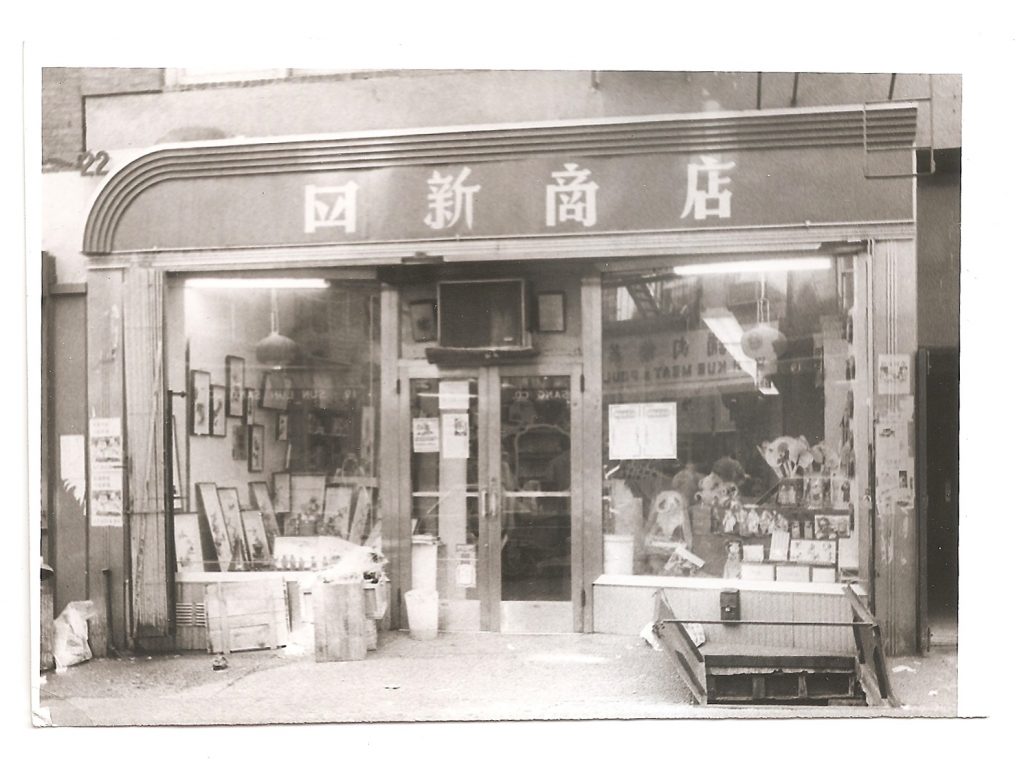

Many of Bocian’s storefront photos offer a glimpse into a vanishing metropolis. As a result of the ongoing evolution from an immigrant enclave into an upscale neighborhood and tourist destination, many traditional small businesses have disappeared since Bocian’s era. (below)

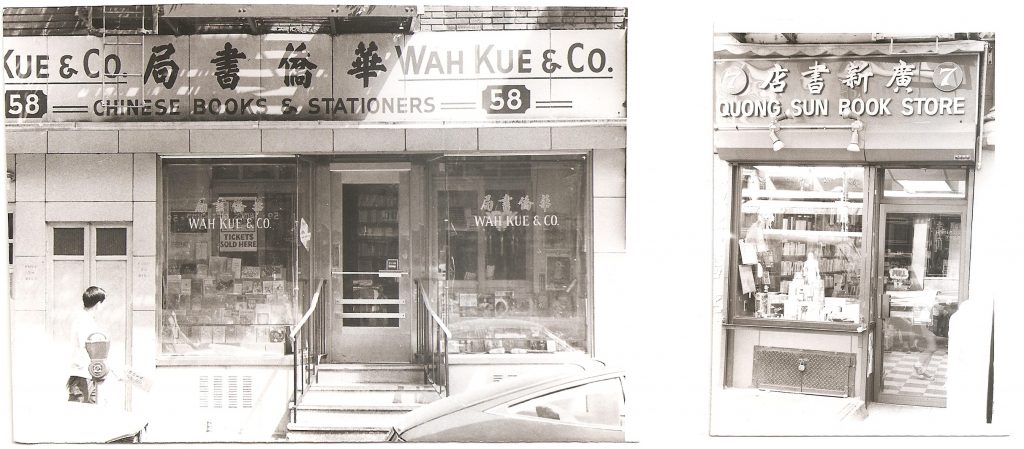

In addition to the general demographic and economic forces conspiring against local small businesses in Chinatown, bookstores like Wah Kue & Co. (below left) and Quong Sun (below right) faced the additional challenges inherent to their business model in the internet era.

In the past several months, the neighborhood has been harder hit than most, beginning with the January 23 fire that consumed the landmark Chinatown building housing MOCA’s archives, known as the “Heart of Chinatown.” Constructed as a public school in 1893, the building, located at 70 Mulberry Street, (left) is currently slated for demolition by October 2020 despite strong community opposition.

Since the earliest days of the COVID-19 pandemic in NYC, the Asian-American community has been subjected to increased instances of racism and xenophobia, symptomatic of similar trends worldwide. As a result, the restaurants and shops of Chinatown suffered a precipitous drop in business well before the mandated city-wide shutdown. A community effort is now underway to save the imperiled independent restaurants of Chinatown, whose razor-thin profit margins make them particularly reliant on high volume for their continued existence. Even in a post-pandemic world, if working from home remains the norm for many, Chinatown businesses that rely on workers from the nearby Financial District, courthouses, and municipal buildings may never recover a significant portion of their customer base.

The staff of MOCA has been working throughout this period of crisis to counter the hatred and racism directed against Asian-Americans and to create spaces for the marginalized to be heard through their One World COVID-19 Special Collection.

The installation of An Unlikely Photojournalist: Emile Bocian in Chinatown, originally planned for late March, has been postponed due to the current closure of the Center for Jewish History. Please check back on our website for updates, and look for additional blog posts in the coming weeks.

SEE PART 3

Lauren Gilbert (co-curator)

Senior Manager for Public Services

Center for Jewish History

I love how this blog celebrates diversity and inclusivity It’s a reminder that we are all unique and should embrace our differences