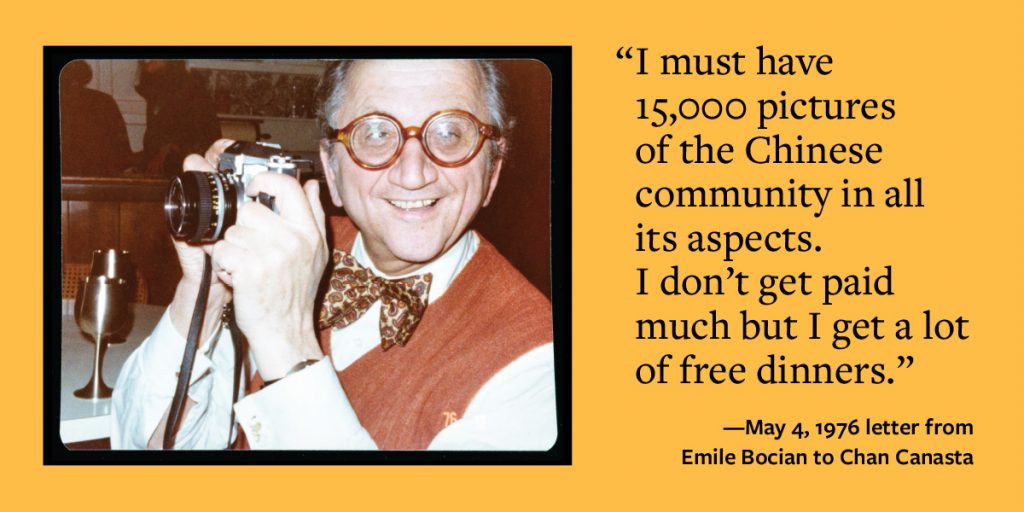

By Lauren Gilbert (co-curator)

Senior Manager for Public Services, Center for Jewish History

An Unlikely Journalist: Emile Bocian in Chinatown, Part 3: ACTIVISM

This is a series of blog posts about the upcoming exhibition An Unlikely Photojournalist: Emile Bocian in Chinatown, a joint project of The Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA) and Center for Jewish History. For an overview of the exhibition and its origins, read this post first.

Among the 120,000 items in the Emile Bocian collection at the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA) can be found numerous photos of protests and demonstrations that took place in Chinatown in the 1970s and 80s. Partially inspired by the Black civil rights campaigns of the 1960s, the Asian civil rights movement gained momentum in the subsequent decades. Many of these images, which depict individuals of all ages rising up against police brutality, poor treatment of refugees, and the city’s perceived disregard for their neighborhood, have particular resonance for contemporary viewers.

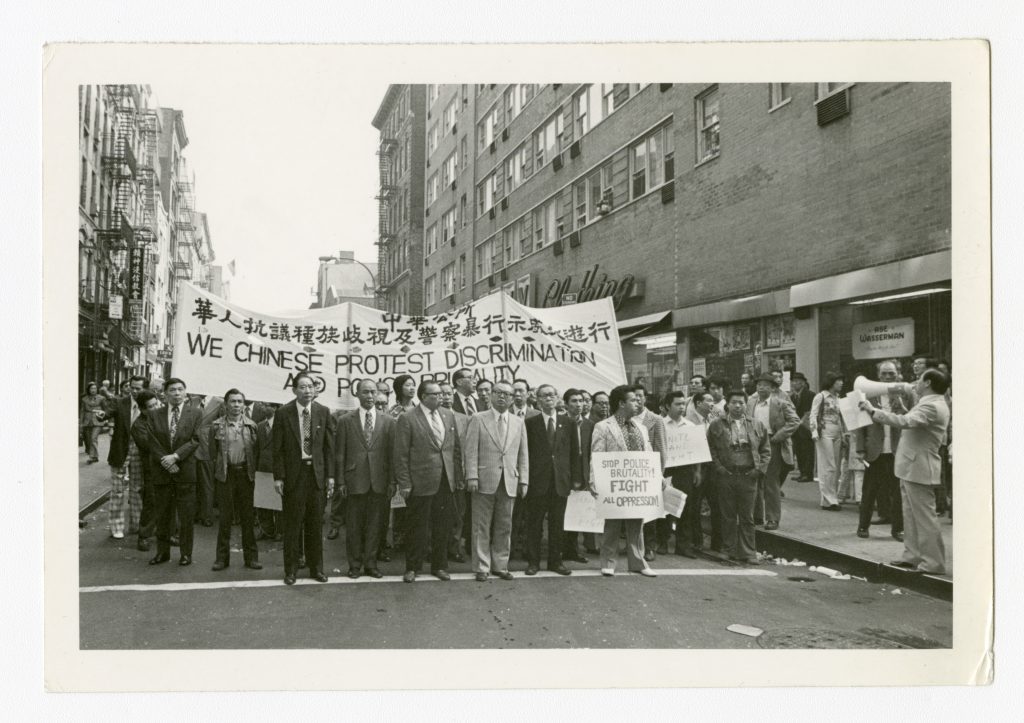

In April of 1975, Peter Yew, a 27-year-old engineer, attempted to intervene in a traffic altercation between two motorists (one white and one Chinese) and was subsequently arrested, beaten, and strip-searched by police officers from the Fifth Precinct. This case of police brutality galvanized the neighborhood. Organized by Asian Americans for Equality, 2500 residents protested the incident on May 12. One week later, the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, the mouthpiece for the more traditional businesses and fraternal groups, organized a demonstration that shut down the entire neighborhood. Twenty thousand individuals of all ages marched from Chinatown to City Hall, uniting around demands for the dismissal of all charges against Yew and an end to discrimination of the Chinese community in all sectors of society, including employment, housing, education, and health (images 1,2). A scuffle broke out between the police and some of the demonstrators at City Hall, at which three police officers were slightly injured, but no arrests were made. Charges against Yew were dismissed in early July, and the commanding officer in the Fifth Precinct was transferred to another post.

This activism was somewhat unexpected in a community that had been considered “one of the city’s more tranquil neighborhoods,” and contradicted the problematic perception of the Chinese community as docile and passive. Demographic changes fueled this new militancy; after the 1965 change to federal immigration law, the Chinatown population skyrocketed, and families replaced what had largely been a community of single adult men. This led to an increase in overcrowding and a resulting strain on health and educational services, as well as a new generation that was both more Americanized and more politicized. Younger residents accused the police of making illegal “stop and frisk” searches of suspected gang members or undocumented immigrants, and of using gambling and gang crackdowns as excuses for brutality and racism.

(In response to the current wave of national and international protests against police brutality, an association of young Chinese-American activists has founded the Chinese For Black Lives initiative, aiming to make New York’s Chinese communities aware of Black Lives Matter and foster solidarity across racial lines. The group has been encouraging businesses in the Chinatowns of Manhattan and Queens to display Chinese For Black Lives posters in their storefronts. The Museum of Chinese in America has also been actively working to encourage Asian-American allyship with Black Lives Matter, hosting a series of online conversations and engaging in frank and open soul-searching.)

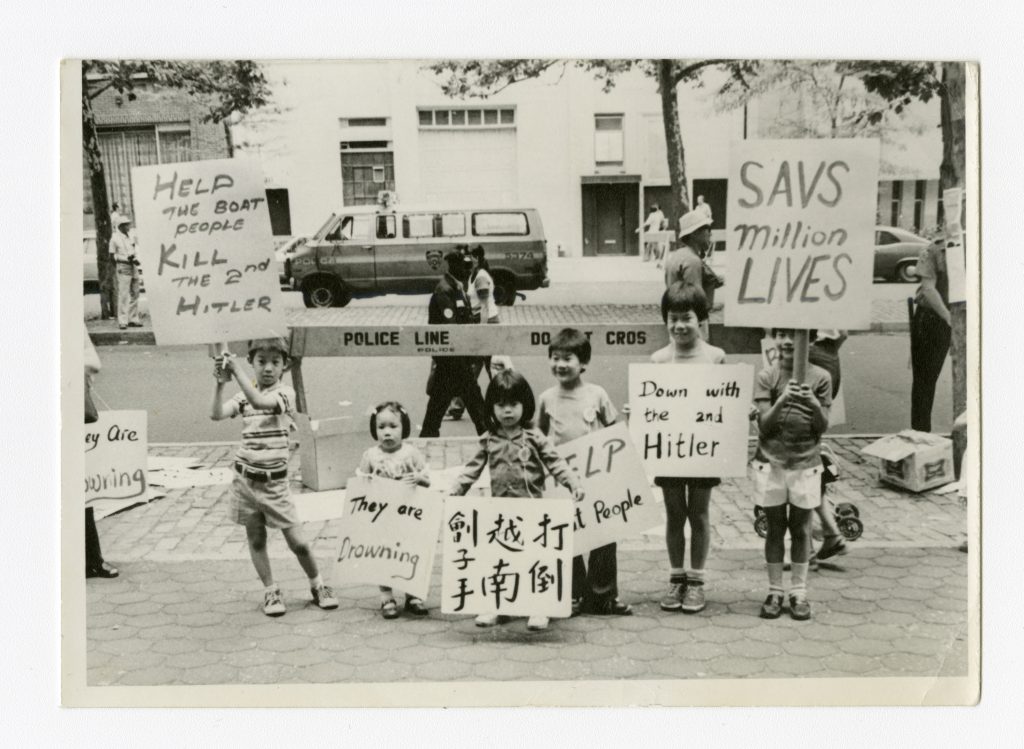

On July 15, 1979, approximately 4,000 New Yorkers, most of Chinese descent, gathered at the United Nations to protest the plight of Vietnamese refugees, known as the boat people (image 3). Approximately three‐quarters of those being expelled from Vietnam were ethnically Chinese. Making an analogy to the treatment of the Jews in Nazi Germany, they carried signs with slogans such as “Stop the Second Holocaust!” The protest was organized by the Committee Against Genocide by Vietnam, a coalition of Chinatown politicians along with Jewish and Christian groups. Among the protestors was Bayard Rustin, a prominent American civil rights leader whose papers are held at the American Jewish Historical Society at the Center for Jewish History.

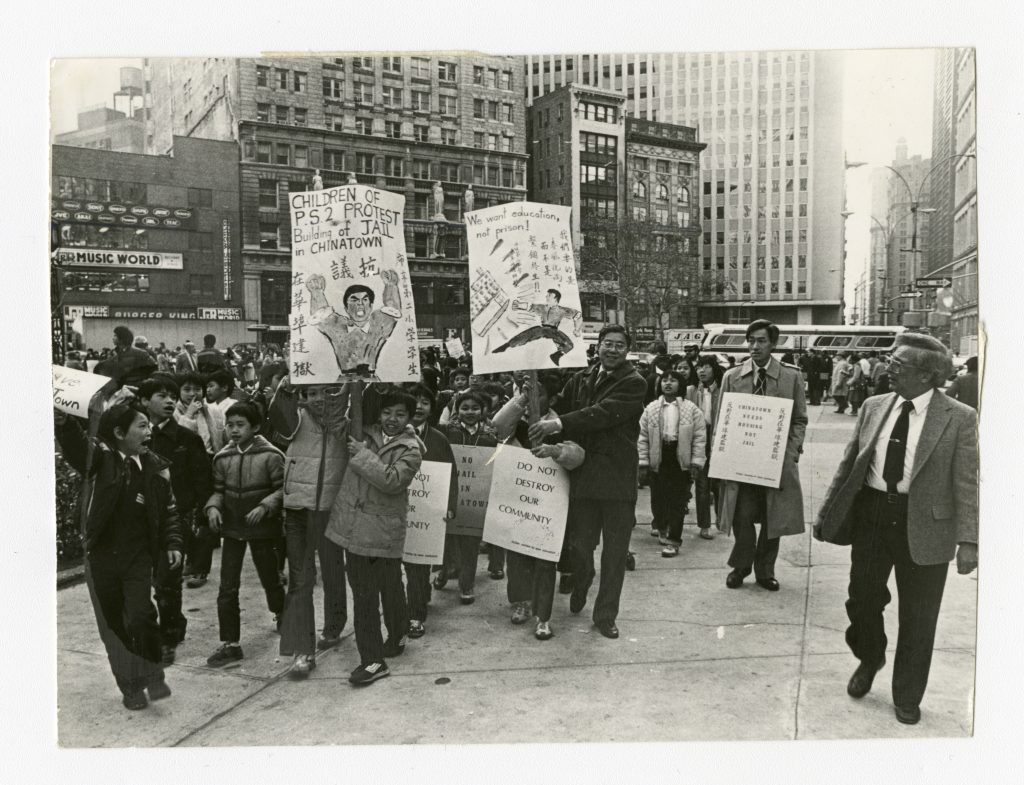

Twelve thousand members of the Chinatown community, including schoolchildren, gathered on November 18, 1982 to protest the building of a jail on the site bounded by Centre, Baxter, Walker and White Streets, insisting that their neighborhood already had a disproportionate share of similar institutions, such as the Tombs jail and the Foley Square courthouses (images 4,5). While the initial protests led the city’s Board of Estimate to delay their vote for one month, the Manhattan Detention Center was ultimately built. At the time, Ed Koch famously quipped. “You don’t vote, you don’t count,” a remark that has been credited for the increase in Chinese-American representation in NYC politics. In October 2019, the community faced a similar predicament and rallied to protest the replacement of the current jail with a larger facility, complaining that they had not been consulted in the planning process and that the new structure would be detrimental to the neighborhood. The rallying cries of “No new jails! Save our seniors!’’ and “Schools! Not jails!” sounded strikingly familiar, nearly 40 years later.

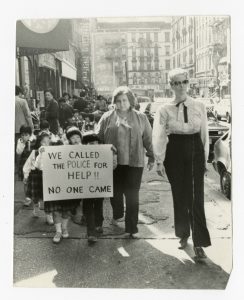

In October of 1984, children marched with their teachers to the NYPD Fifth Precinct, protesting a lack of response by the police (images 6.7). It is unclear what event precipitated this demonstration. (If you have any information about this protest, feel free to provide it in the comments section below.)

An interesting footnote to the history of activism in Chinatown includes a case of support for the Jewish relief effort as far back as 1903, in the form of a Chinese-organized benefit performance for victims of the Kishinev pogrom that had killed 49, injured 500 and left 2,000 Jewish families homeless in the Russian provincial capital. The event was organized by a successful Chinese businessman named Joseph Singleton, who had arrived in New York 20 years earlier. Along with other Chinatown reformers, Singleton was opposed to the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act and subsequent legislation that had ended most Chinese immigration into the United States, and felt solidarity with other groups suffering from persecution.

The opening of An Unlikely Photojournalist: Emile Bocian in Chinatown, originally planned for March, has been postponed due to the current closure of the Center for Jewish History. Please check back on our website for updates about the opening date.

1 comment