By Lauren Gilbert

Senior Manager for Public Services, Center for Jewish History

Sermons of Thanksgiving

It is widely believed that the Pilgrims modeled their Thanksgiving feast after the Jewish holiday of Sukkot. In its modern incarnation as a secular festival focusing on gratitude, an appropriately Jewish concept, Thanksgiving has been observed by American Jews from its earliest days.

When George Washington declared a non-denominational National Day of Thanksgiving in 1789, American Jews eagerly joined the celebration. Gershom Mendes Seixas (right), the first American-born Jewish religious leader, was serving as cantor at New York’s Congregation Shearith Israel, the first Jewish congregation established in North America. An ardent patriot, Seixas had insisted on closing the synagogue during the Revolutionary War, rather than continuing to operate under British occupation. In 1789, Seixas was one of 14 clergymen participating in the inaugural Thanksgiving celebration. Drawing upon scripture, he delivered a sermon in which he expounded upon the special responsibilities of the Jews to “support that government which is founded upon the strictest principles of equal liberty and justice.”

The holiday was only sporadically observed until 1863, when President Lincoln proclaimed a National Day of Thanksgiving to be held on the last Thursday of every November, largely due to years of persistent lobbying by magazine editor Sarah Josepha Hale, who believed such a day would help ease divisions between North and South.

Throughout the 19th century and into the following, it was common for places of worship to hold services on the holiday. Several Thanksgiving Day sermons delivered in synagogues were later published and are held in the collections of the American Jewish Historical Society at the Center for Jewish History.

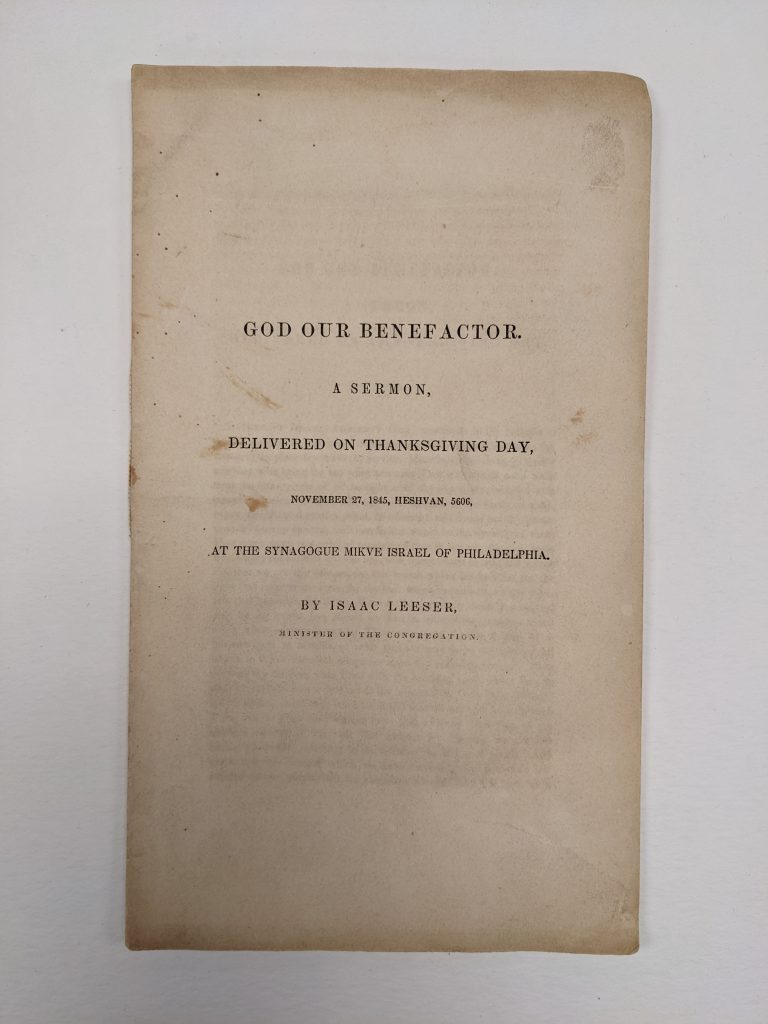

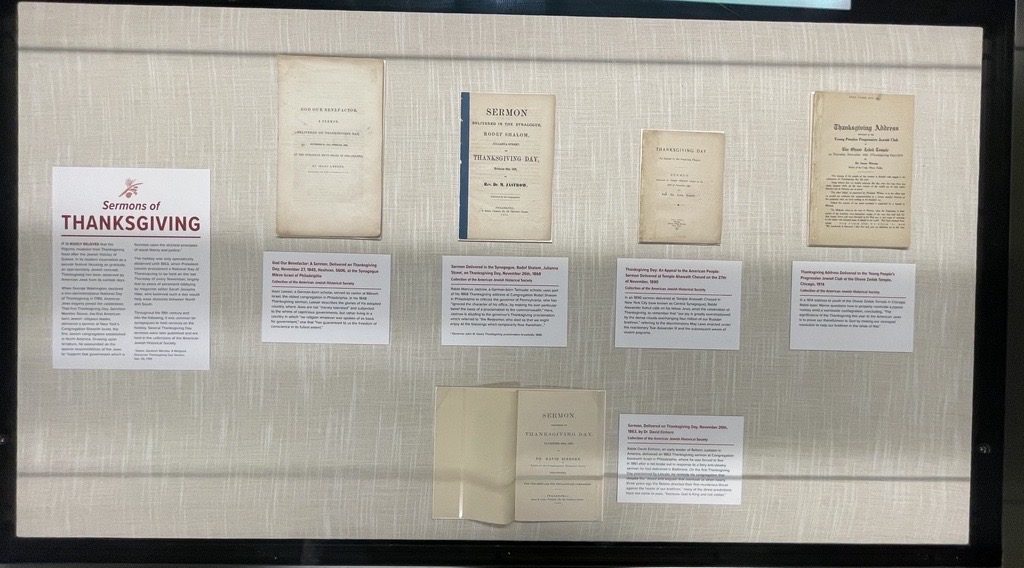

Isaac Leeser, a German-born scholar who produced the first American Jewish English translation of the Torah, and subsequently of the entire Tanakh, served as cantor at Mikveh Israel, the oldest congregation in Philadelphia. In his 1845 Thanksgiving sermon, Leeser acknowledged that the congregation was coming together not for the “usual duty of our religion,” but rather “in obedience to …the chief magistrate of the commonwealth…to return thanks to the Giver of all good, for the many blessings which this land enjoys.” He described the glories of his adopted country, where Jews were not “merely tolerated” and subjected to the whims of capricious governments, but rather living in a country in which “no religion whatever was spoken of as basis for government,” one that “has guaranteed to us the freedom of conscience in its fullest extent.” (Pictured below. Collection of the American Jewish Historical Society.)

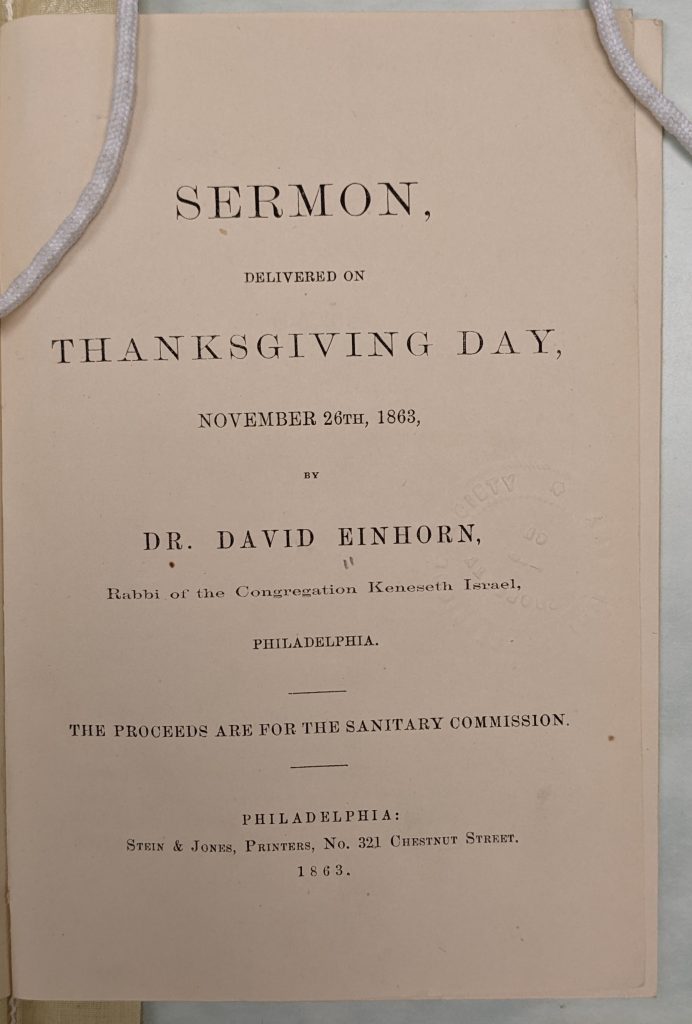

Rabbi David Einhorn, an early leader of Reform Judaism in America, delivered an 1863 Thanksgiving sermon at Congregation Keneseth Israel in Philadelphia where he was forced to flee in 1861 after a riot broke out in response to a fiery anti-slavery sermon he had delivered in Baltimore, Maryland, then a slave state. On the first Thanksgiving Day proclaimed by Lincoln, Einhorn acknowledged “the manifold blessings that God has bestowed upon us during this terrible crisis of a civil war.” He reminded his congregation that despite the “dread and anguish that overtook us when nearly three years ago the Rebels directed their first murderous thrust against the hearts of our brethren,” many of the direst predictions have not come to pass, “because God is King and not cotton.” (Pictured below. Collection of the American Jewish Historical Society.)

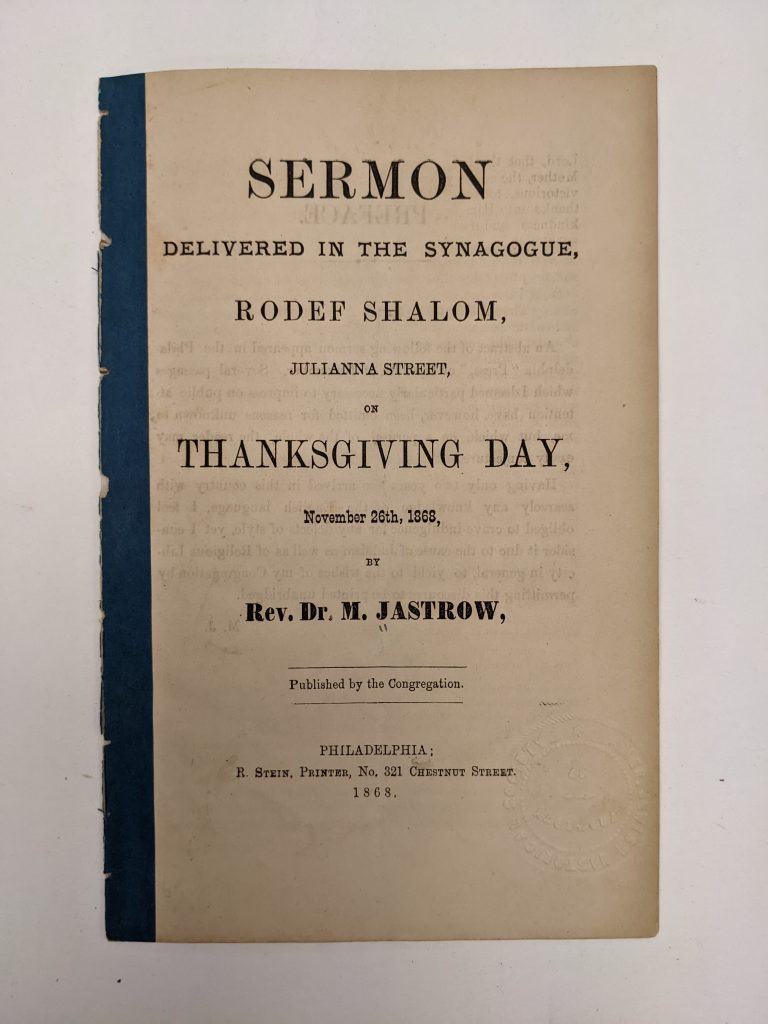

Rabbi Marcus Jastrow, a German-born Talmudic scholar, used part of his 1868 Thanksgiving address at Congregation Rodef Shalom in Philadelphia to criticize the governor of Pennsylvania, who had “ignored the character of his office…by making his own particular belief the basis of a proclamation to the commonwealth.” Here, Jastrow is referring to the governor’s Thanksgiving proclamation, which had mentioned “the Redeemer, who died so that we might enjoy all the blessings which temporarily flow therefrom…”1 Similar dustups over the exclusionary Christian wording of state Thanksgiving proclamations occurred in multiple locations throughout the 1800s. (Pictured below. Collection of the American Jewish Historical Society.)

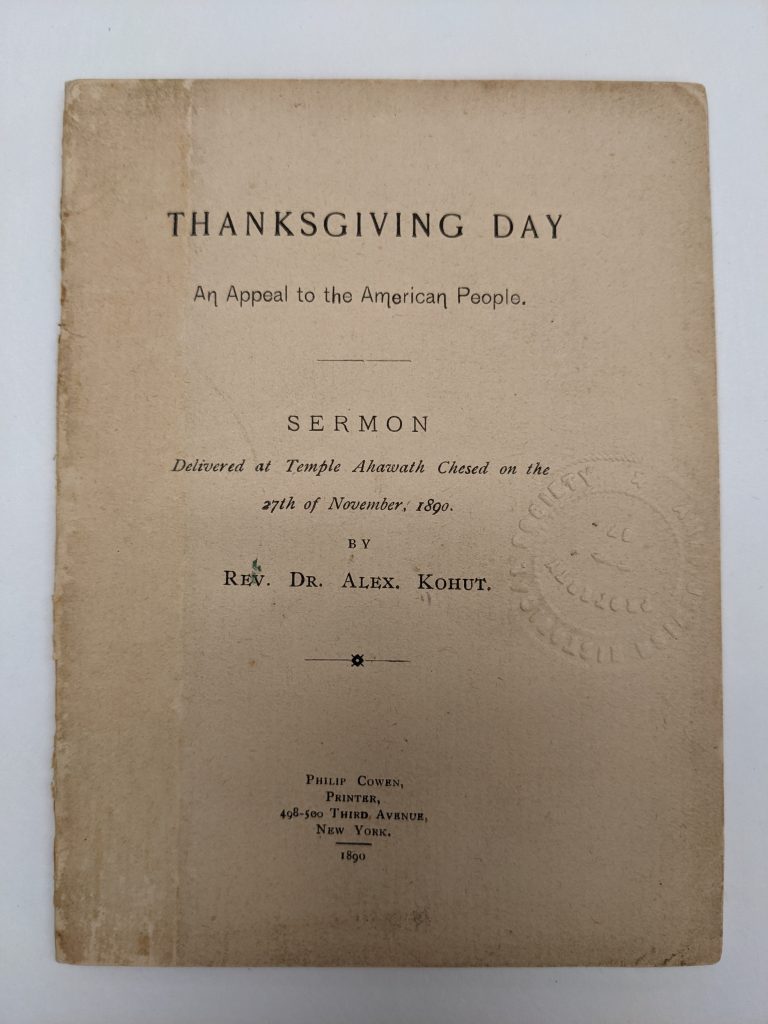

In an 1890 sermon delivered at Temple Ahawath Chesed in New York City (now known as Central Synagogue), Rabbi Alexander Kohut, one of the founders of the Jewish Theological Seminary, reminded his congregants that “America is the only land on the globe which grants the sons of Israel unconditional rights, indisputable political freedom, and absolute liberty of thought and conscience.” Amid the celebration of Thanksgiving, he called on Jews to remember that “our joy is greatly overshadowed by the dense clouds overhanging four million of our Russian brethren,” referring to the discriminatory May Laws enacted under the reactionary Tsar Alexander III and the subsequent waves of violent pogroms (Pictured below. Collection of the American Jewish Historical Society.)

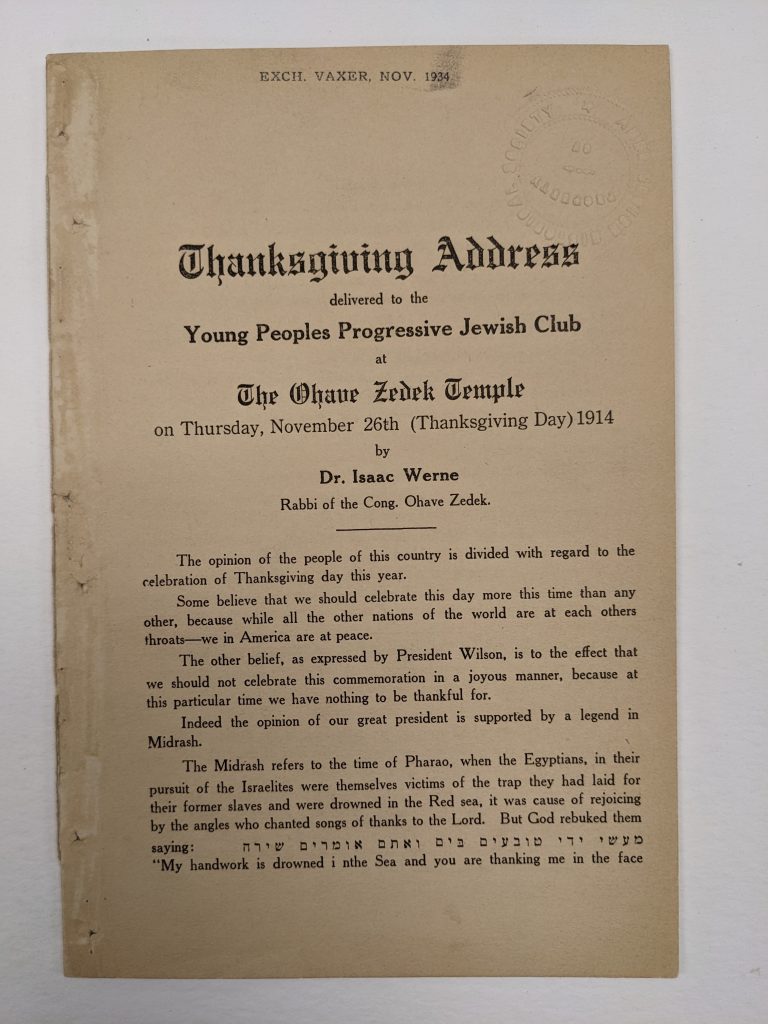

In a 1914 address to youth at the Ohave Zedek Temple in Chicago, Rabbi Isaac Werne questioned how to properly celebrate a joyous holiday in the midst of a worldwide conflagration, concluding, “The significance of the Thanksgiving this year to the American Jews is to prove our thankfulness to God by making our strongest resolution to help our brethren in the lands of War.” (Pictured below. Collection of the American Jewish Historical Society.)

As early as 1906, Thanksgiving services in synagogues were “meagerly attended,” according to an article reporting on remarks by “Jewish ministers.”2 In the following century, the trend only continued, with family time, meal preparation, football games, and the Macy’s parade all overtaking religious services as preferred Thanksgiving Day activities. Bucking the trend, however, is Shearith Israel in New York City, which has been conducting Thanksgiving Services ever since 1789, when Gershom Mendes Seixas first urged his congregants to take part in the political life of the fledging republic.

Below: Sermons on display in the Lillian Goldman Reading Room at the Center for Jewish History in November, 2022. All items courtesy of the American Jewish Historical Society. Click here to see a time-lapse video and photos showing the conservation treatment these items received for this exhibit.

An extremely interesting post. I enjoyed reading the historical references which show the intention of Jews, from the early days, eager to join in the celebration of Thanksgiving. And how intriguing to know that it might have been a concept modeled on Sukkot!

I agree wholeheartedly with Nina Levy’s comments (and not just because she’s my mother).

Thank you for this most informative article. Just yesterday I read in a periodical distributed in my state by local merchants stating that Thanksgiving is a Christian holiday started by Christians to honor “our Lord Jesus Christ.” These false statements are being sent to every home in my state and I find it very disturbing. I would suggest that everyone try to share the CJH blog to friends and relatives. We must counter the untruths promoted by religious fanatics at a time when antisemitism is again on the rise.

Just another example of how Jews have always mightily tried to adopt customs of the home country, most particularly the United States . . . how far we have traveled as Speaker of the House invokes Christian bible as basis for his political aims, former President speaks of those who disagree with him as “vermin,” and many march to protest Israel while many march in support. What is old is new again! We are obligated to continue to be a light to all generations throughout the world.