Campfire Magic: Pluralism of Jewish Summer Camping

Today, many think of summer camp as a uniquely Jewish phenomenon. In reality, Jewish educational camps developed as a branch of American organized camping. At the turn of the 20th century, camping was a major tenet of American Progressivism and the Fresh Air Movement, which sought to provide relief for poor immigrants in overcrowded cities during the summer, while also assimilating them into American culture. The first Jewish camp was established in 1893 by the Jewish Working Girls’ Vacation Society, then called Camp Lehman and later renamed Camp Isabella Freedman, now owned by the Jewish environmental organization Hazon. The first Jewish camps were Jewish because of their constituency or because they were run by Jewish communal organizations, not because of their mission.

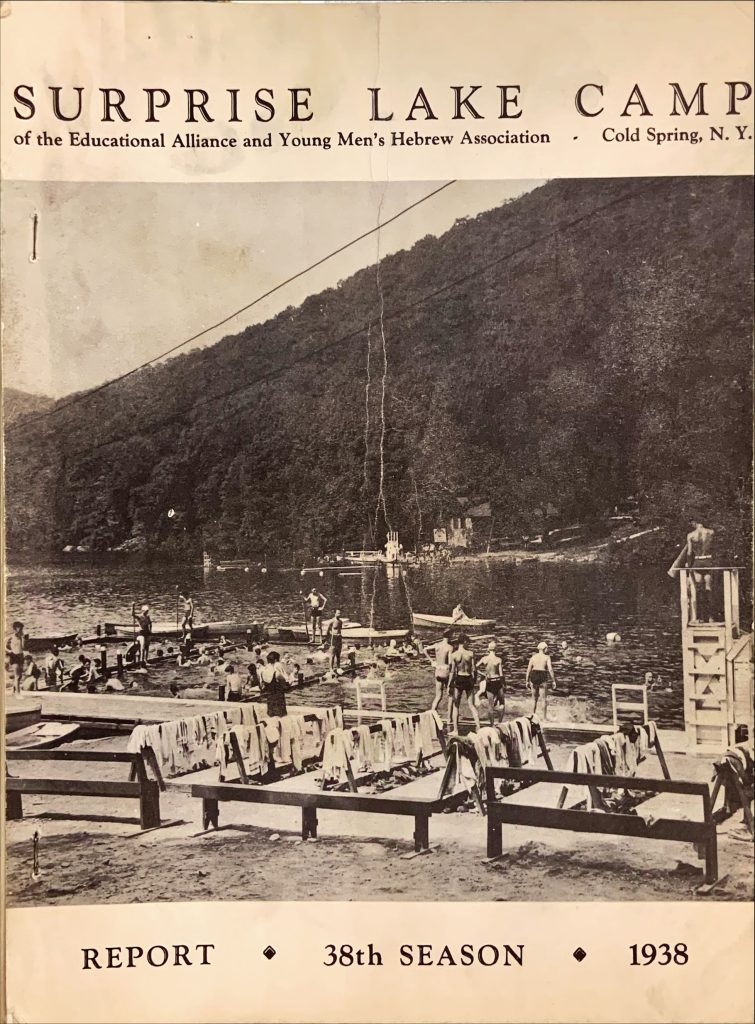

Surprise Lake Camp is one of the oldest and best-known Jewish camps in the country. It originated as a Fresh Air camp in 1902 run by the Educational Alliance, originally a settlement house for East European Jews immigrating to New York City. Jewish immigrant boys from the Lower East Side stayed for two-week periods. At the time, Jewish camping enthusiasts believed an emphasis on self-sufficiency and outdoor recreation effectively countered antisemitic stereotypes concerning Jewish weakness. After World War II, the camp became co-ed with a nondenominational Jewish educational mission. Both Surprise Lake Camp, as an independent nonprofit, and the Educational Alliance still exist today.

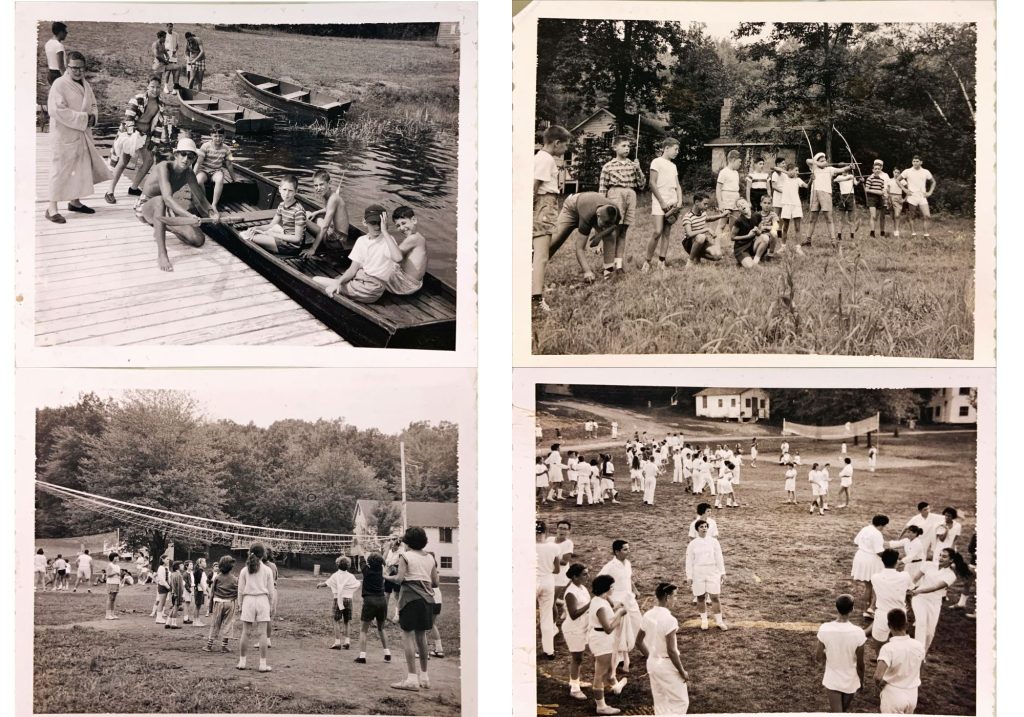

The next generation of Jewish camps founded in the 1920s had an explicitly Jewish ideological mission and were determined to reinforce Jewish identity by making Jewishness the norm of the camp experience. Camping has its own kind of magic— a unique sense of community generated through an isolated setting and a totally closed environment. Founders realized that they could harness this to make Jewish learning fun, natural, and seemingly effortless. During this period until the 1950s, many Jewish camps believed they could simultaneously meet the religious needs of a wide range of Jews by maintaining a “traditional” Sabbath observance, but without strict allegiance to any religious movement. This tradition of pluralism within Jewish camping hearkened back to the idea that the community, rather than the synagogue, should oversee Jewish education and assumed that culture unified Jews even as religion divided them.

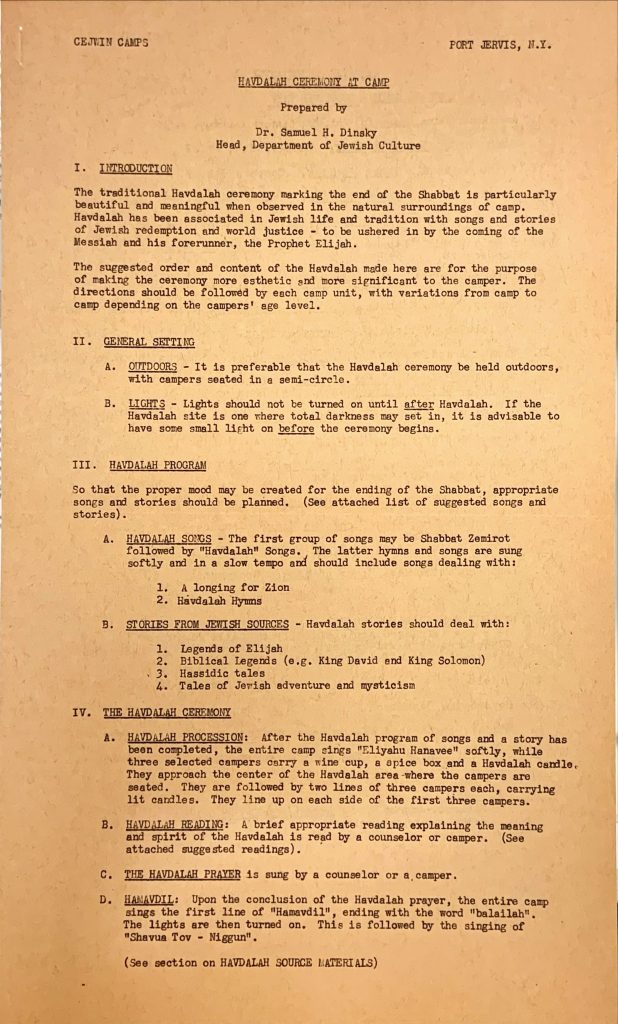

Cejwin Camps, founded by Albert P. and Bertha Schoolman in 1919, was the first camp with a Jewish educational mission. At first, it was affiliated with the Central Jewish Institute (CJI), an independent Jewish community Center in Manhattan, to implement year-round educational programming coinciding with their Talmud Torah school. By the 1930s, Cejwin was a cultural Jewish camp influenced by European Zionist youth movements, appealing to lower middle-class families who sent their children to progressive Jewish schools. The camp focused on informal Jewish education through singing, dancing, and pageantry, as well as elaborate Shabbat celebrations and Tisha B’Av commemorations. After WWII, the camp was very intertwined with Hadassah due to Bertha Schoolman’s involvement with the Youth Aliyah program. Cejwin Camps closed in 1991.

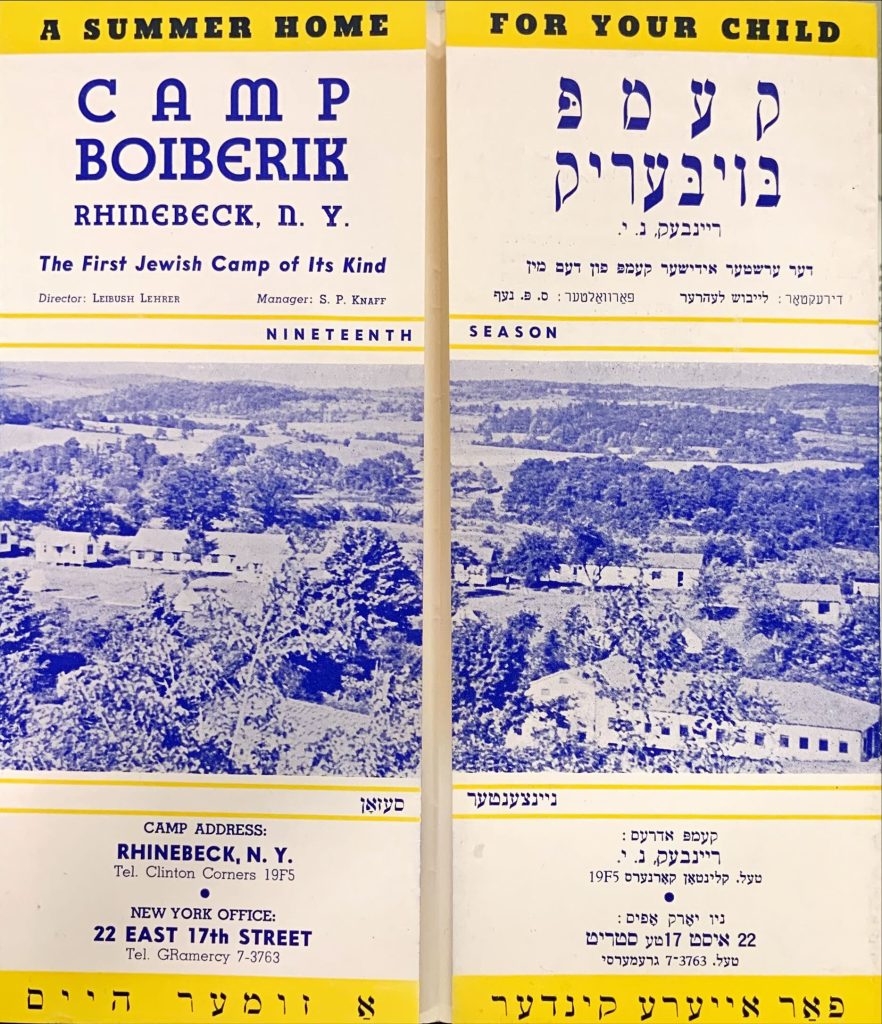

Camp Boiberik, founded in 1919 by the Sholem Aleichem Folk Institute and Leibush Lehrer, was a non-denominational Yiddish cultural and linguistic camp framing Yiddish as central to Jewish creative life and education. It was politically non-partisan, unlike other Yiddish camps which were socialist, communist, or Zionist. The camp also embraced Jewish ritual more than other camps. Lehrer believed that Jewish rituals function in the Diaspora to advance and deepen feelings of belonging and actively express the shared history of the Jewish people. After World War II, Boiberik became more ideologically and emotionally centered around Yiddish since most campers were third generation Americans and had little knowledge of Yiddish except for phrases and idioms. Camp Boiberik closed in 1979.

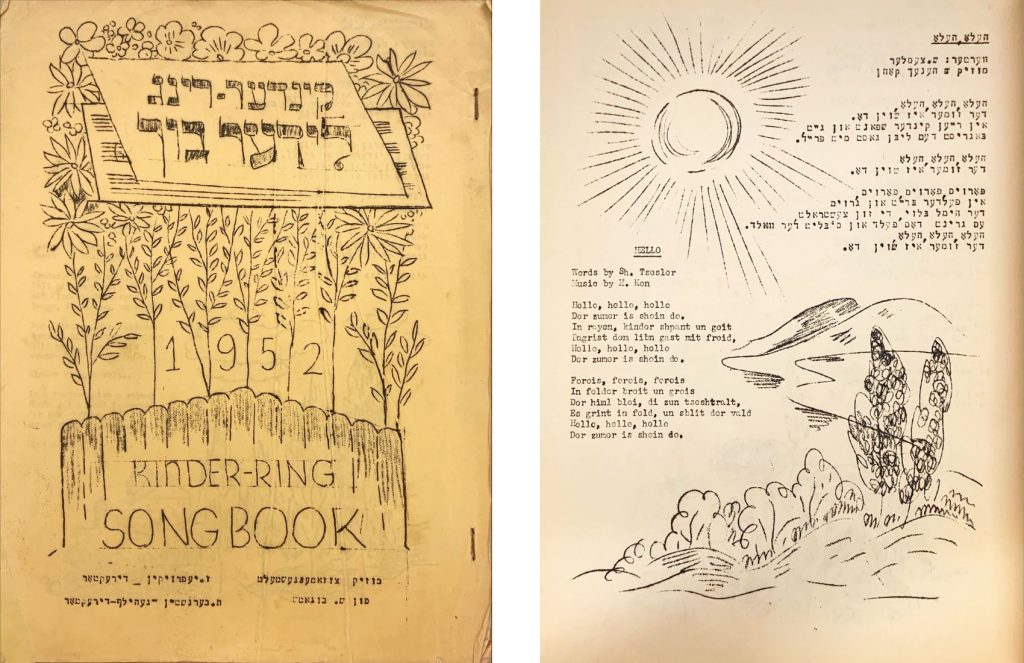

Camp Kinder Ring was established in 1927 by the Workers Circle, then a socialist mutual aid society, to give its members and their children a summer home away from the city. The Workers Circle was organized in 1900 by Jewish immigrants seeking a cultural community in which to express their heritage, educate their children, and unite for mutual aid and social justice activism. Today, both organizations, with Kinder Ring as an independent nonprofit, share the mission of promoting Jewish community, Yiddish culture, and social justice.

Jewish camps often wrote their own songs to fit their needs and interests and produced new song books every year. Song-leading is a way to create a sense of spirit, unity, and identity among campers. It is also an instructional tool for communicating knowledge. Songs can be incorporated into any activity, such as campfires, hikes, bus trips, meals, and camp-wide programs.

By the 1940s there was a major rise in camps associated with Jewish religious movements. Before 1940, about two thirds of all new Jewish camps were either philanthropic, geared to the children of immigrants and the urban Jewish poor, or community-based camps founded by Jewish federations and community centers. From 1940-1960 almost 40% of camps had Jewish educational and religious aims, sponsored by a religious movement or a Hebrew cultural institution. In a post-World War II world, there was a camp for every kind of Jew: cultural, Zionist, Yiddishist, Hebraist, Socialist, Conservative, Reform, and Orthodox.

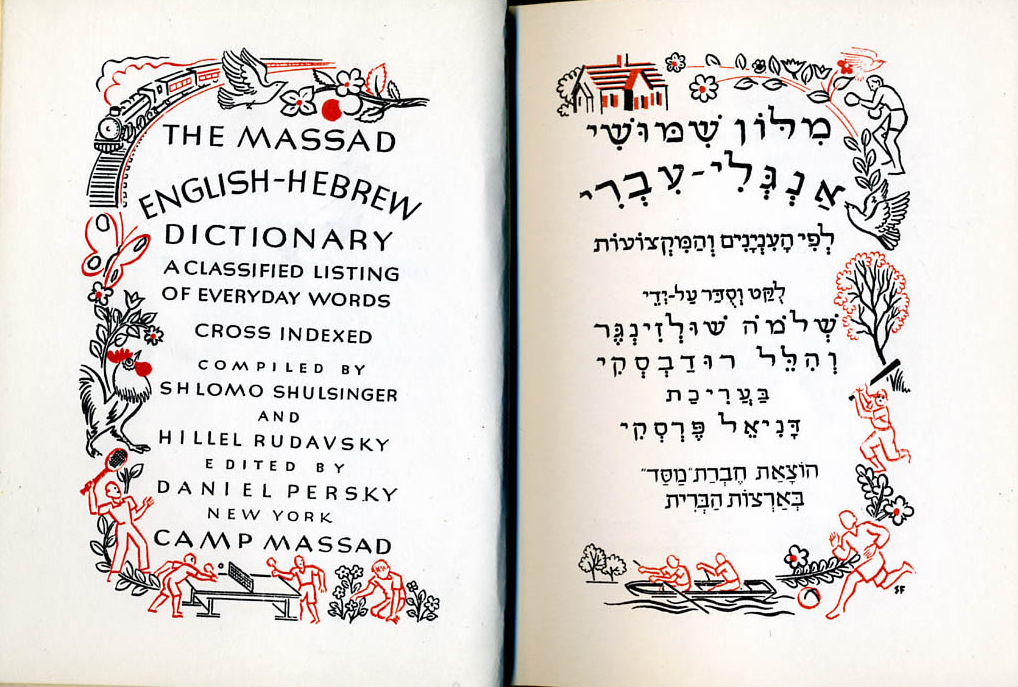

Camp Massad, founded by Shlomo and Rivka Shulsinger and associated with Histraduth Ivrith, opened in 1941 as a Hebraist and Zionist camp. They wanted campers to experience what an “authentic” Jewish life in Israel might be like. Campers engaged in Zionist practices like agricultural work and hiking which reflected the ideals of returning to the land and making it productive. Kabbalat Shabbat and Havdalah incorporated Israeli dancing and singing. All activities were in conversational Hebrew, and words were invented when necessary. At first, Massad was non-denominational and attracted campers of diverse backgrounds. During the 1960s, the camp became more Orthodox in response to the rise of Conservative and Reform camps. During its peak years from 1966-68, it had an enrollment each summer of more than 900 children across three camps. Camp Massad closed in 1981.

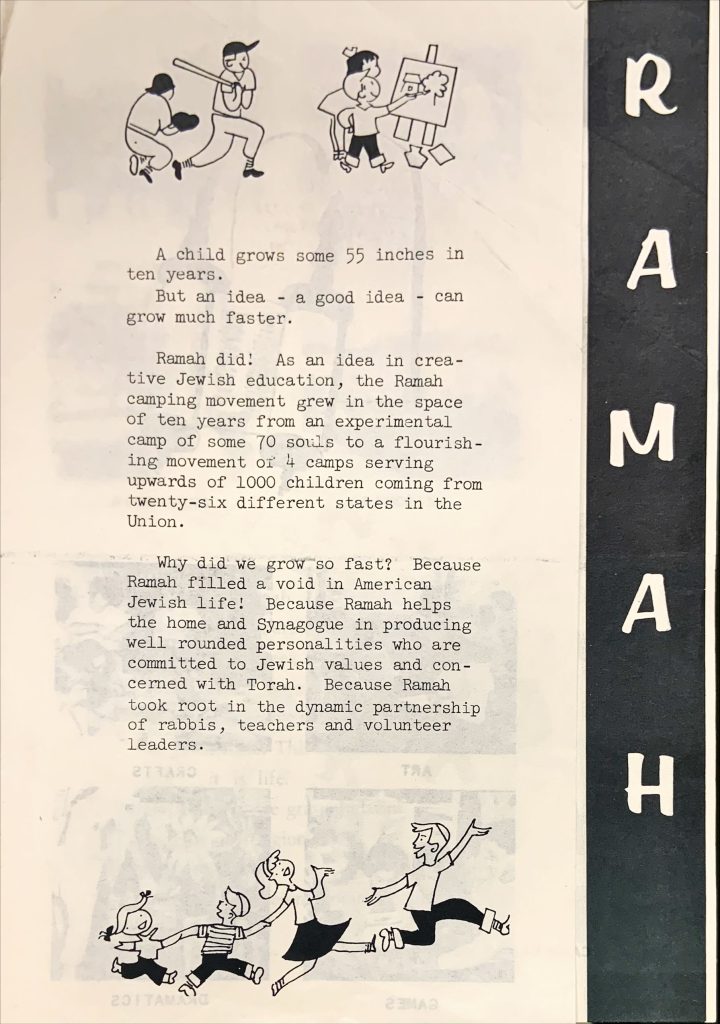

Camp Ramah is perhaps the best-known denominational Jewish summer camp. The first Camp Ramah in Wisconsin opened in 1947. Today, there are 11 Ramah overnight camps, serving youth associated with the Conservative movement. Ramah from its origins was linked to the Jewish Theological Seminary, which trained Conservative rabbis and educators, and not to the United Synagogue of America, the umbrella organizations for Conservative synagogues. The camps emphasize the teaching and daily use of Hebrew language, the fostering of religious and spiritual development, and the strengthening of Jewish and Zionist identity through extensive Israel programming.

Sara Belasco

Reference Services Librarian, Special Collections

Center for Jewish History

If you are interested in seeing what other material the Center’s partners have about Jewish summer camps, then check out our research guide.

Sources:

Lehrer, Leibush. Camp Boiberik: the growth of an idea. 1959.