By Ella Jordan-Smith

Reference Services Librarian, Center for Jewish History

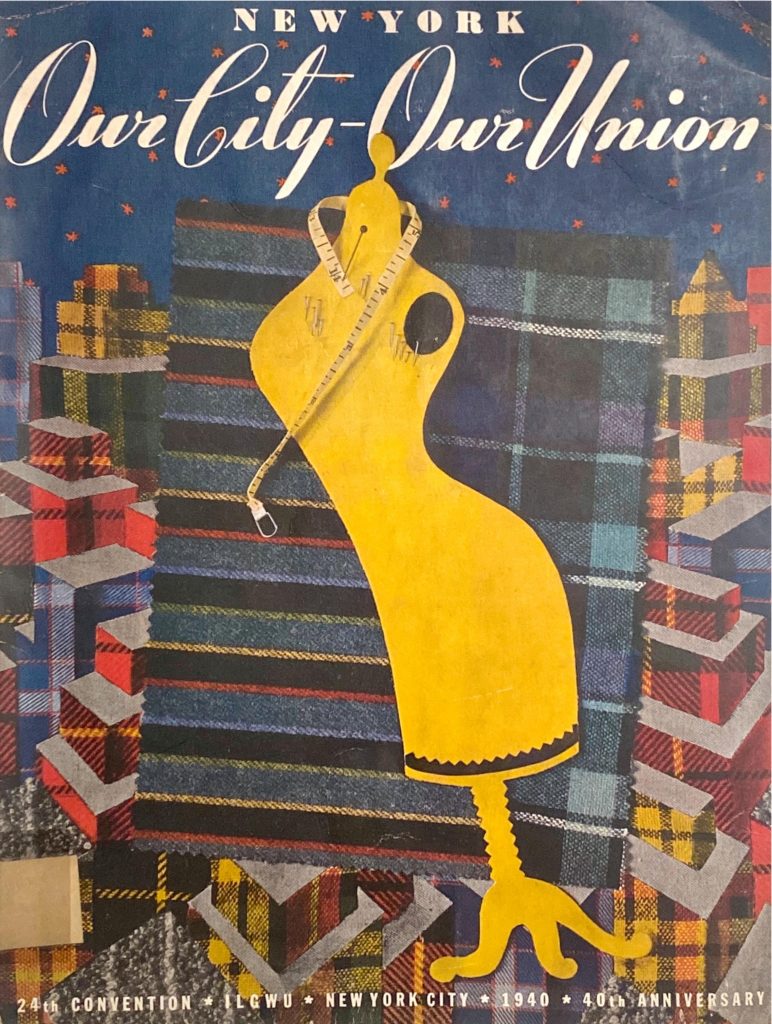

Building a Jewish Union and the ILGWU

In 1900, eleven delegates representing seven major local unions in the Northeast convened to form the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union. All eleven of these delegates were Jewish men (the “ladies” in the organization’s name refers to the garments, not the constituency) who represented unions composed of primarily Jewish immigrants in major industrial cities such as New York, Newark, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. The ILGWU was an industrial union, meaning it served all workers in the ladies’ garment industry, rather than being separated by job or skill set. From the beginning, the ILGWU was inherently Jewish, both in its demographics and its culture. It was also one of the first unions to be made up predominantly of women.

Due to the influx of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe at the turn of the 20th century, the American union movement was heavily influenced by Jewish immigrants bringing over Yiddish culture and unionist ideals. There was no better industry for this influence to take hold than the garment industry, particularly in New York City where the industry was flourishing, and most factories were already owned by German Jews who had immigrated earlier in the 19th century.

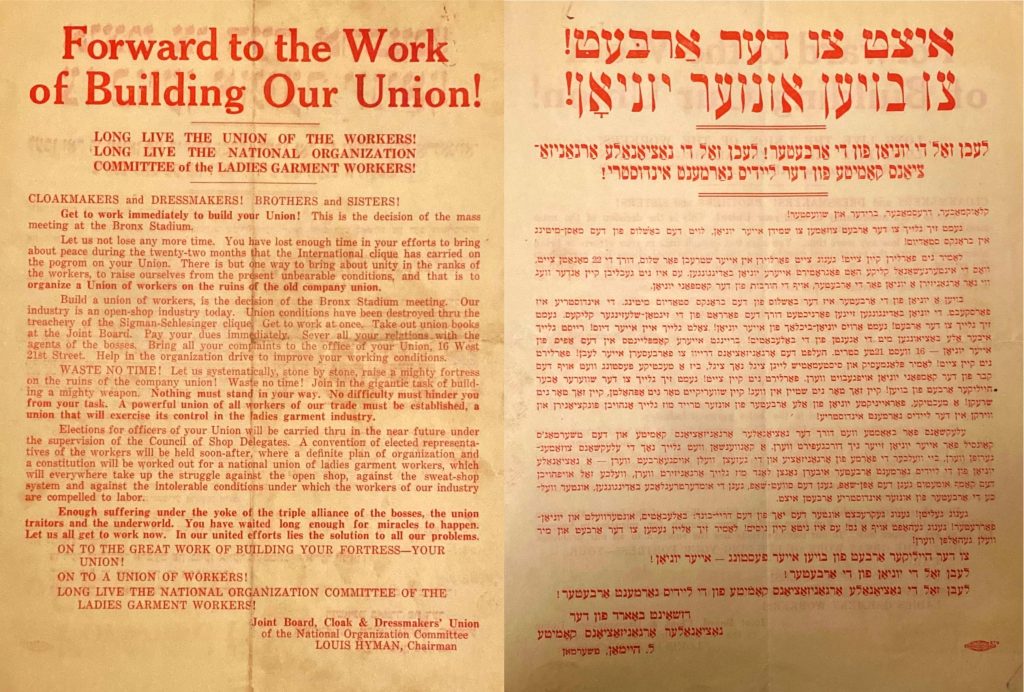

In the first few decades of the ILGWU, most material was printed in English and Yiddish (see above), which accurately reflected the composition of workers in the garment industry at that time. Between 1899 and 1910, the garment industry employed nearly two thirds of all Jewish wage-earners in NYC.

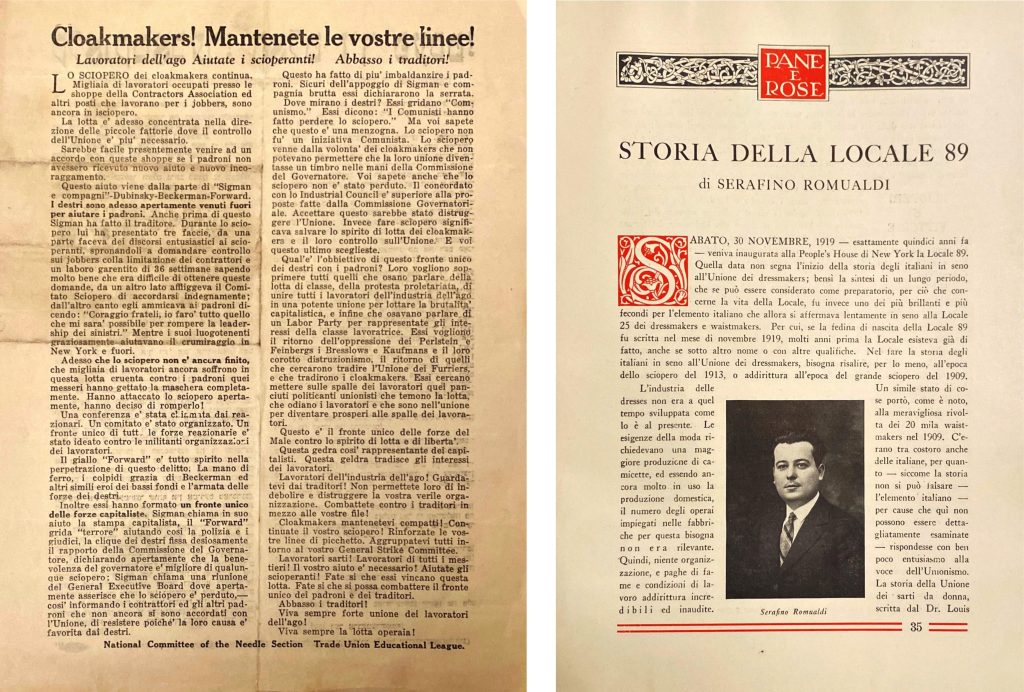

In the 1910s, the Italians were the first group to join member unions in large enough numbers to challenge a culture in which all information was distributed and decisions were made in Yiddish. They were able to receive the establishment of Italian-language based locals within the ILGWU (see above).

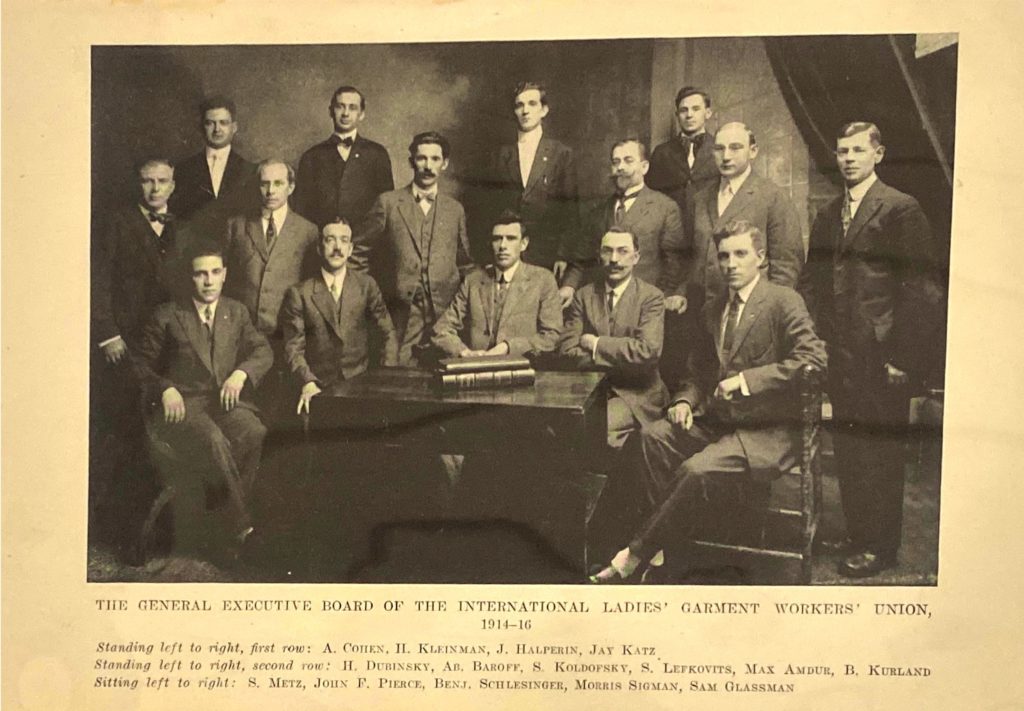

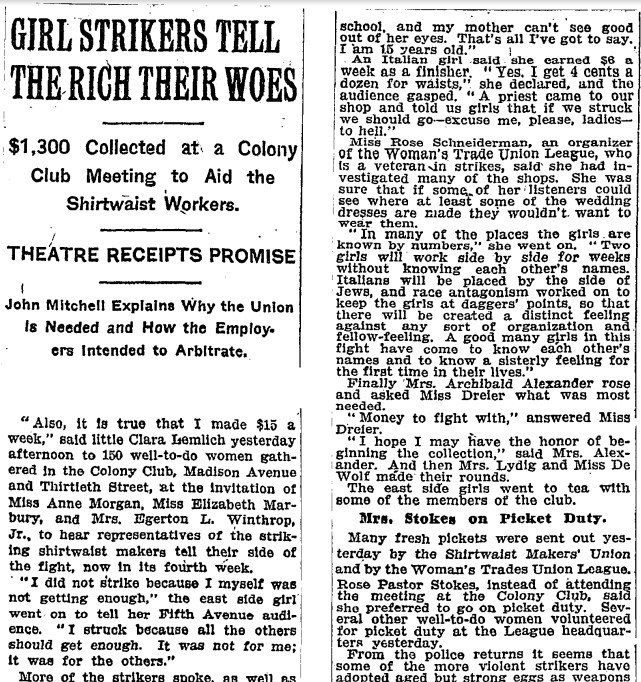

As evidenced by this photo of the General Executive Board from 1914-16 (above), in the first decades of the union, there were very few women in positions of power, which inaccurately reflected the union’s demographic of predominantly women, particularly young Jewish women like Clara Lemlich and Rose Schneiderman (see below), who were fervent union organizers. In 1909 the composition of workers in the garment industry was 80 percent female.

Clara Lemlich immigrated to the US as a teenager with her family from a village in what is now Ukraine in 1903. When she arrived in New York, she found work in the garment industry. Her experiences convinced her of the need for labor reform through unionization. She eventually went on to be elected to the executive board of Local 25 of the ILGWU in 1905. At that time, all top union leaders were men who typically thought only “skilled” workers, usually men, could effectively organize. But it was Clara who demanded and led the great Uprising of 20,000 in 1909, which lasted for thirteen weeks. No other union leaders were willing to demand a general strike, until Clara stood up from the crowd of thousands at a strike meeting at Cooper Union and yelled out in Yiddish, “I am a working girl. One of those who are on strike against intolerable conditions. I am tired of listening to speakers who talk in general terms. What we are here for is to decide whether we shall strike or shall not strike. I offer a resolution that a general strike be declared now.” Lemlich then took the famous Yiddish oath to strike the following day, pledging, “If I turn traitor to the cause I now pledge, may this hand wither from the arm I now raise.”

David Dubinsky, pictured on the bottom right (above), served as President of the ILGWU from 1932 to 1966. Dubinsky immigrated to the U.S. from Poland where he had been affiliated with the Jewish Labor Bund. This was fairly common for members of the ILGWU in the first quarter of the 20th century; many had fled Eastern Europe due to pogroms and the failed revolution of 1905.

Under Dubinsky’s presidency the union doubled its membership and expanded its reach into the Southern and Western states. By the 1960’s the ILGWU’s membership was far more diverse due to its geographical reach and the changing demographics of immigrant populations. This meant that the union had drastically less of a Yiddish cultural focus. As the garment industry in the US shrunk and moved overseas, there was a steady downturn in the strength of the ILGWU, and in 1995, the ILGWU merged with the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union to form UNITE.

The materials discussed above are on exhibit in the Lillian Goldman Reading Room at the Center for Jewish History through February 2024.

Selected Additional Resources at the Center for Jewish History:

Records of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union (I-309)

Common Sense & a Little Fire : Women and Working-class Politics in the United States, 1900-1965 /

Look for the Union Label : A History of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union

The Women’s Garment Workers : A History of the International Ladies’ Garment Worker’s Union

Was there a founder who was the brother of Hersch or Harry Weiss aka Weissman?