By Lauren Gilbert, Director of Public Services

“A Virtuous, Honest, Industrious, and Injured Foreigner”: The Case of Henry Simons

All publications referenced in this post can be found in the Sid Lapidus Collection of Early Modern Judaica at the Center for Jewish History.

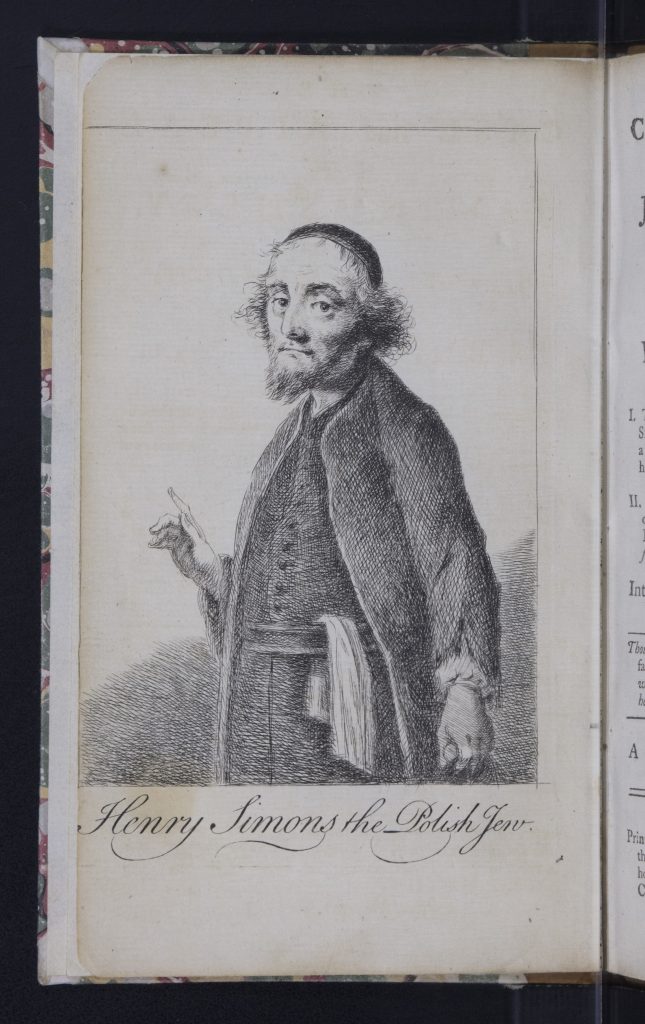

In August of 1751, a Polish Jewish peddler named Henry Simons traveled to England carrying 554 ducats that had been entrusted to him by Polish nobles to “purchase the Manufactures of this Nation for their Account.” Unfortunately for him, as described in the 1753 publication The Case of Henry Simons, a Polish Jew Merchant [see below], the trip did not go as planned.

According to this account, Simons, “of a very good Jewish family,” lodged in London “at the House of one Berend Abrahams in Dukes Place.” After setting out to Bristol to purchase goods, he decided to turn back to London due to sore feet. On his way, he inquired about lodgings but was turned away and “treated with the utmost Ill-nature by the Landlord of the House.” Before he left, a gardener “who was greatly intoxicated with Liquor” asked him a question in English, which Simons did not understand, and so shook his head in response. The man took this as an affront and “pulled him by the Beard,” which is “one of the most unpardonable Insults that can be offered a Foreigner of his Religion.” The gardener then pursued Simons angrily on foot, whereupon Simons was valiantly protected by four English gentlemen on horseback.

When Simons set out again, he was refused entry at an inn by a woman who did not like his “Appearance and Dress.” Afraid he would have nowhere to stay, Simons opened his purse to show that he could pay for his lodging and was then given a room. However, early in the morning he was robbed of all his money, and when he cried out, one of the robbers “wounded him in the head” and held a knife to his throat. When told of the affair, the innkeeper “gave himself no manner of Trouble about it, and only laughed and ridiculed the poor Man.” Back in London, “Mr. Thomas Woodman, Keeper of the Poultry-Compter,” who witnessed Simon’s injuries, procured a warrant for the arrest of the innkeeper.

At the subsequent trial, the innkeeper was acquitted “by Artifice, Contrivance, and insidious Suppression and Secretion of Evidence, with the detestable Addition of willful and corrupt Perjury.” In this telling, the worst offense was committed by James Ashley, a friend of the innkeeper, who explained Simons’ injuries away with the invention of an unrelated dustup on the road.

Having been robbed of his funds, Simons was reliant on alms from the London Jewish community. He even pawned his tallit (“his veil, which is a religious vestment worn by the Jews in their Synagogue, and what they will not pawn or dispose of, unless compelled thereto by the extremest Necessity”). To make matters worse, Simons was himself later tried and convicted of perjury, based on Ashley’s testimony that Simons had in fact placed ducats in Ashley’s pocket to falsely make him appear guilty, which he likened to Joseph’s conduct toward Benjamin in the Bible.

After this latest outrage against a “Virtuous, Honest, Industrious, and Injured Foreigner,” the Jewish community in London came together to assist Simons. They made a successful application for a new trial, at which several witnesses attested to his character, including Aaron Franks (“the great Jew Franks, and the ruler and head of the synagogue”). At this trial, Simons was found not guilty, and his defenders published this pamphlet outlining his travails.

Not to be outdone, Ashley responded with his own publication “in full refutation of everything contained in the said pamphlet,” entitled The Case and Appeal of James Ashley of Bread-Street, London [see below]. In his version of the tale, Ashley bemoans the fact that a new trial had been granted to “Simons, the Jew,” who had been “fairly tried and convicted of a Capital Misdemeanor.” He lays out his case in detail, which includes the claim about Simons “trickingly conveying Three Ducats, in a juggling Manner, into my Pocket.” Most tellingly, he asserts that a Jew is not “bound to speak the truth…in a Christian court.”

This pamphlet battle was taking place at a pivotal moment in English Jewish history. Although Cromwell had readmitted the Jews in 1657, centuries after their expulsion in 1290, they had not been given the protections or rights of citizenship, which was a hot topic in the mid-18th century. In 1739, an act had been passed to provide for the naturalization of foreign Protestants and Jews after seven years of residency, though this was only eligible to those living in the colonies, not in England proper. The so-called Jew Bill of 1753, Parliament’s first attempt to grant full citizenship to Jews residing in England, was passed in 1753 but promptly repealed after a huge antisemitic uproar [see below].

As in our own time, public debate often took the form of sensationalized or falsified reports of criminal actions committed by members of the community whose rights and legal status were under discussion. This case, among several others, became a symbol of the disputes between Jews and “native” Englishmen.

View the digitized documents discussed above:

The Case of Henry Simons, a Polish Jew Merchant

The Case and Appeal of James Ashley of Bread-Street, London

An act to permit persons professing the Jewish religion to be naturalized by Parliament