By Miriam Udel, Rifkind Fellow 2024-2025 & Member of the CJH Academic Advisory Council

What Shall We Tell the Children?

As I demonstrate in my critical study Modern Jewish Worldmaking Through Yiddish Children’s Literature, the Yiddish children’s literary canon that burgeoned on the secularist left during the first half of the twentieth century forms a rich archive for revisiting the anxieties and ideas that animated Ashkenazi modernity. This literature emerged from politically aligned fraternal organizations, each with its own network of schools and allied publishing programs. We can tease out adults’ ideological aspirations and intuitions from the corpus of nearly one thousand books—short stories, novels and novellas, poems, and plays—and several periodicals that they devised for the young readers in their midst.

But what about more programmatic statements regarding education and ideology? Starting in the 1930’s, educational theorists and leaders, as well as rank-and-file teachers in the Yiddish after-school systems, talked among themselves in pedagogical bulletins. On unassuming mimeographed and stapled pages, they articulated their understanding of the best educational practices; shared primary source materials, lesson plans, and games for use in the classroom; and disseminated quantitative education research. The Buleten launched in March 1935 as a project of the Yiddishist, ostensibly “non-political” Sholem Aleichem Folk Institute schooling network.¹ The Bundist, explicitly socialist Arbeter ring (Workmen’s Circle, renamed Workers Circle in 2020) launched its own periodical in 1939. In November 1941, both of these periodicals joined together under the aegis of the Jewish Educational Commission, henceforth to be known as the Pedagogisher buletin and placed under the editorship of grammarian, educational theorist, pedagogue, and children’s author Yudl Mark (1897-1975).²

Mark moved the monthly in a more theoretical and philosophical direction, opening every issue with an editorial-cum-essay about the focus of special issues or just topics of special concern. Because his tenure spanned most of the Holocaust, the founding of the State of Israel and other significant milestones, perusing the Pedagogisher buletin allows us to track how Mark and his colleagues, or khaveyrim-lerer, sought to teach about these events at every phase of children’s development and education.

Pedagogisher buleṭen, November 1941. Collection of YIVO Library.

The inaugural issue of the Pedagogisher buletin [above], under Yudl Mark’s editorship. Mark spells out plans for the publication and summarizes the contents of precursor publications. Items include language drills and literary materials suitable for classroom use.

In the November 1941 inaugural issue, Mark explains the pre-history of the new publication and recapitulates the contents of both precursor bulletins, bemoaning the children’s poor knowledge of the Yiddish language. Two months later, in January 1942, Y. Brumberg reinforces this theme, noting that many students are third-generation Americans who must learn Yiddish as a foreign language. The bulletin leans into the latest science on foreign-language instruction, reviewing relevant professional material in English.

By the start of the new school year in September 1942, Mark writes on “The War and Our School Program,” setting a course he will follow throughout the Holocaust when he observes, “We must acquaint children with the tragic situation.”³ He imparts biblical heft to the theme a month later with an essay called “And You Shall Tell Your Child….” In February 1943, Yudl Mark offers a meditation on real-time Holocaust pedagogy, musing that teachers ought to embed the necessary facts within oral storytelling, scaled to the sensitivities and capacities of their pupils. As suitable subjects, he offers an escalating scale of horrors from “burning Jewish books” to “Jewish soap.”

The opening of Mark’s essay “And You Shall Tell Your Child…” Pedagogisher buleṭen, December 1942.

The opening of Mark’s essay “And You Shall Tell Your Child…” Pedagogisher buleṭen, December 1942.

Collection of YIVO Library.

Not all was bleak. A special issue in November 1949 pondered the application of John Dewey’s progressive educational theories in the Yiddish schools. Despite the Sholem Aleichem network’s apolitical genesis, the Pedagogisher buletin celebrated the formation of the Jewish State, even as they grappled with the challenges it posed: the January 1950 issue took for granted that there would be “Hebrew in Our Schools” but weighed the question of whether the pronunciation would be Ashkenazi (closer to Yiddish) or Sephardi (in keeping with Modern Hebrew), while the March 1950 special issue considered “The Place of Israel in Our School Curriculum.”

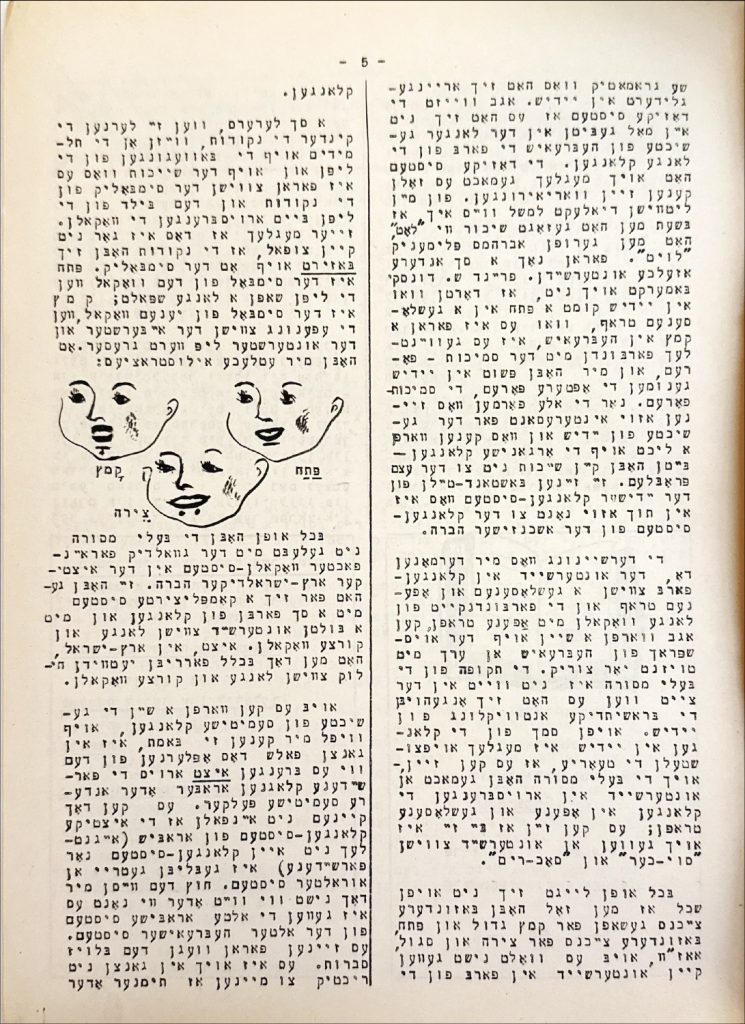

January 1950, p. 5. “Hebrew In Our Schools—With Ashkenazic or Sephardic Pronunciation.” Explaining that Modern Hebrew pronunciation has elided the earlier distinction between long and short vowels, the diagram illustrates the author’s claim that the Hebrew vocalic system originally reflected the visible position of the lips when forming each vowel sound. Pedagogisher buleṭen, January 1950. Collection of YIVO Library.

¹In her study of the New York-based Yiddish children’s periodicals, Naomi Prawer Kadar observes that the rise of the Nazis reversed a trend toward universalism and de-emphasizing particularist Jewish content, whether it took the form of Zionism or Jewish religion. See her study Raising Secular Jews: Yiddish Schools and Their Periodicals for American Children, 1917-1950. Waltham, MA: Brandeis UP, 2017.

²For more on Mark’s educational activities, see Burko, Alec Eliezer. “Saving Yiddish: Yiddish Studies and the Language Sciences in America, 1940-1970.” PhD diss. Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 2019.

³Pedagogisher bulletin 9 (Sept. 1942), p. 3