by Ilana Rossoff, Reference Services Research Intern, Center for Jewish History

This post is part of the Jews and Social Justice Series. To view all posts in the series, click here.

Jews for Urban Justice (JUJ) organized programs that used Jewish holidays as opportunities to raise awareness about social injustices and expand on traditional Jewish spiritual practice. On July 23, 1969, Jews for Urban Justice held a Tisha B’av service on the steps of the U.S. Capitol building in protest the proposed Anti-Ballistic Missile System. As Michael Staub describes, the services aimed to commemorate the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem and connect it to a moment in which mass destruction felt imminent. They invited all Jewish members of Congress, and in the end, 100 people were in attendance [8].

On September 21, 1969, one of JUJ’s most active members and supporters, Rabbi Arthur Waskow, gave a Kol Nidre sermon at Tifereth Israel Congregation in D.C. entitled “The Confession,” which caused controversy when members of the audience felt offended by the rabbi’s explicit references to racism and militarism as sins for which they must atone [9].

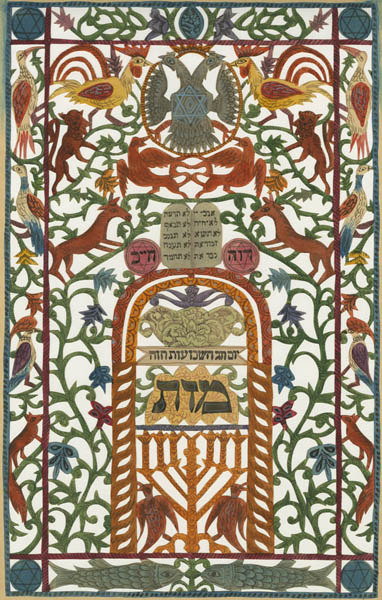

One of the most memorable political/spiritual efforts of JUJ was its Freedom Seder, its politically-charged Passover seder that incorporated pressing issues of the time into its message for liberation from bondage for all. Rabbi Arthur Waskow’s Haggadah, The Freedom Seder: A New Haggadah For Passover, had its debut at this multi-racial, political seder held in the historically African-American church, Lincoln Temple. The seder was attended by over 800 Jewish liberals, radicals, Black militants, hippies, and others. It was covered by numerous Jewish and progressive media outlets and inspired the formation of the National Jewish Organizing Project by members of JUJ and other Jewish radicals to emulate the work of JUJ on the national level. [10]

Jews for Urban Justice also organized numerous educational forums and initiatives that reached out to Jewish youth. They hoped to speak to their disillusionment with establishment Jewish culture and offer them a politically-engaged alternative. In a May 1970 internal article entitled “Where do we go from here?,” founder Mike Tabor writes how D.C.-area youth are entirely turned off by the major Jewish communal institutions, and that Jews for Urban Justice must make it their “only priority” to reach young people “with positive Judaic values.” On the necessity of bringing substantive political programming to youth, he writes, “Our ability to transfer some of our own feelings, understanding, and commitment to our brothers and sisters around us will determine whether we become a group that acts like a social club or one that functions as a movement” [11].

According to JUJ’s July 1969 report on their activities, they formed a “radical Jewish Sunday School,” a “Jewish high school group” and were going to establish a “Freedom Sunday School” [12]. In May 1970, they developed a proposal for a summer program entitled “The Jewish Festival House,” which would offer retreats, silk screening, workshops on public speaking and Sabbath celebrations with “a constant dedication to the achievement of personal liberation through the building of true community” [13]. They also held a discussion series entitled “The Jewish Urban Underground” for which they brought in such speakers that would lead discussions on “sexism, community, Israel, the police state, Marx and the Jews, the Palestinians, class warfare, and collectivizing our lives.” A clause on the bottom of the poster reads: “establishment & Jewish assimilationist press will not be admitted!” [914].

Staub writes that JUJ members were involved in the initial formation of the Fabrangen community center, intended to be a center for Jewish youth culture but limited in its political functions by its funders. Staub cites the progressive depoliticization of the center—combined with other factors such as JUJ members moving on to work with other (usually more political) organizations—as the cause for Jews for Urban Justice’s end in July 1971. [15]

Jews for Urban Justice began with the mission to target those Jewish individuals and institutions who perpetuated racism, militarism and oppression in the D.C. community. It evolved to incorporate much more community outreach, radical youth community formation, solidarity organizing with the anti-war and Black freedom struggles and radical Jewish practice into its work. While this shift reflected where its members’ passions lay, members had also made the conscious choice that “Jewish institutions are not the major enemy,” as quoted by Staub [16]. Similarly, in “Where do we go from here?” Mike Tabor also writes that a year or so before the time of his writing, the group had agreed that “the American-capitalistic-melting-pot-system (and not establishment Jews) was the real enemy” [17].

Staub writes that the group’s retreat in March 1969 was where they reflected on their work and made this decision, which he claims resulted in part from the amount of backlash they received from major Jewish institutional leadership. Nonetheless, according to Staub, the group remained committed to highlighting the actions and in-actions of Jewish institutions, just not exclusively [18]. As such, they were successful in building a community of radical Jewish youth that engaged their spiritual beliefs and connection in radical political work.

While I am not aware of the specific numbers that the organization claimed during its time, its overall impact can be measured by the hundreds of people it brought out to such events as the Freedom Seder, its number of strong relationships with clergy and organizations, its number of educational and community-building events it held in various parts of DC, its founding of the National Jewish Organizing Project, and, in my opinion, the potency of its mission of bringing together the power of Jewish spirituality and radical political practice.

Notes:

[9] “The Confession” Kol Nidre 5730, 21 September 1969. Folder" Yom Kippur, 1969, Jews for Urban Justice collection, American Jewish Historical Society archives. Also Staub, pages 171-172

[10] Staub, 163-168

[11] Mike Tabor, Draft: “Where do we go from here?” Folder: Statement of Purpose, Membership Form, and Membership List, Jews for Urban Justice collection, American Jewish Historical Society archives here at the Center.

[12] Activities of “Jews for Urban Justice” 1967-1969. 14 July 1969. Folder: Programs: 1067-1970 & undated, Jews for Urban Justice collection, American Jewish Historical Society archives here at the Center.

[13] A Proposal For a Summer Program from Jews for Urban Justice, May 1970. Folder: Programs: 1967-1970 & undated, Jews for Urban Justice collection, American Jewish Historical Society archives here at the Center.

[14] Poster: The Jewish Urban Underground, undated. Folder: Programs: 1967-1970 & undated, Jews for Urban Justice collection, American Jewish Historical Society archives.

[15] Staub, 184-190 .

[16] Staub, 163.

[17] Mike Tabor, “Where do we go from here?”

[18] Staub, 163.

Further Reading:

David Glanz, “An Interpretation of the Jewish Counterculture,” Jewish Social Studies, Vol. 39, No. ½, American Bicentennial: II (Winter – Spring,1977), pages 117-128. This article can be found in the JSTOR database accessible here at the Center.

Jews for Urban Justice archival collection, American Jewish Historical Society archives. The Electronic Finding Aid to the archival collection can be found here.

Susan Agus, Bobbie Baom, Leslie Cheffer, Baila Goldstein, Iris Kodish, Rosalie Riechman, Sharon Rose, Arlene Rosenbaum, Adrianna Weininger and Chava Weissle, “j.u.j.” Off Our Backs, Vol. 1, No. 21 (May 6, 1971), p. 14. This article can be found in the JSTOR database accessible here at the Center.