In honor of Women’s History Month, I

would like to offer some guidance to those who are seeking to discover and

share the stories of their elusive female ancestors. One of the most common

“brick walls” that genealogy researchers face when tracing the family history

of a female ancestor is that their family doesn’t know her maiden name. For

centuries in much of the Western world, the practice of women replacing their

surname with their husband’s surname upon marriage has effectively severed

these individuals from their genealogical lineages. Learning a woman’s maiden name is a crucial

first step for the modern researcher trying to find documents that shed light

on a woman’s early life (prior to her marriage) or that trace her ancestry back

to previous generations.

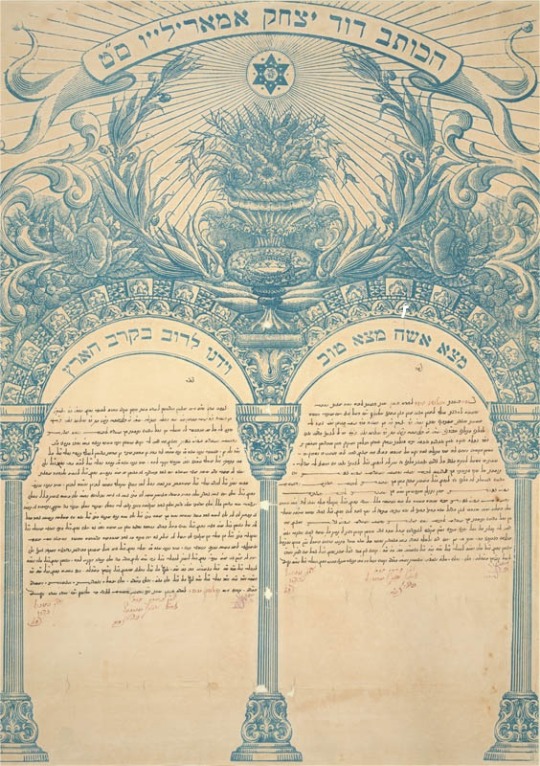

Marriage contract of Yitzhak son of

Moshe(?) Benjamin and Palomba daughter of Shulami Halevy; artist: David Isaac

Amarillo; Salonika, 1897; Lithograph on paper with handwritten text.

Collection of Yeshiva University

Museum, New York

Gift of Grace Grant

Ironically,

the very documents which mark the occasion on which women are typically stripped

of their maiden names are the ones that hold the greatest potential as the

source of those names. Of course, I am referring to a woman’s marriage records.

Depending on the place, time, and religious affiliation of the wedding, any

number of records may have been issued to show the couple’s intent to marry,

such as marriage banns, intentions, bonds, newspaper announcements, licenses,

and applications, and to document the actual wedding, such as marriage

contracts (the ketubah in the Jewish

tradition, pictured above), registers, and certificates. With the exception of

those that are passed down as family heirlooms, historical religious marriage

records have scarcely survived. On the other hand, civil marriage records, even

centuries old, are much more likely to have been maintained by a local clerk,

registrar, or archives to the present day. For more information on how to

locate U.S. marriage records, please consult the Ackman & Ziff Family

Genealogy Institute’s vital records research guide here. For

international marriage records, please select our research guide pertaining to

your ancestor’s country of marriage

When

a marriage record cannot be located or does not contain a maiden name, there

are a number of alternative sources to pursue, beginning with other types of

vital records. The birth records of a woman’s children are the second best

source for her maiden name, because most birth records solicit that information

and the informant (i.e. the person who supplied the information) is typically

the woman herself. Records pertaining to a woman’s death, such as death

certificates and registers, cemetery ledgers, gravestones, obituaries, and

probate records, should be used with caution. If the informant is identified on

the document, think about whether that person is likely to have accurately

recalled the deceased’s maiden name. If the informant is not identified, think

about whether the deceased’s closest surviving relatives are likely to have

recalled her maiden name. When in doubt, try to corroborate the name supplied

with additional sources. Further guidance: U.S. birth records, U.S. death records, international records by country.

There are several less commonly used U.S.

sources of maiden names that may help you when the aforementioned sources fail.

First, if your female ancestor was already married when she emigrated to the

U.S., check her and her husband’s immigration records (also known as passenger

arrival lists or manifests). They may have identified the woman’s father or one

of her brothers (all of whom shared her maiden name) as their closest living

relative in their native country or as the relative who they were joining in

the U.S. Second, review your female

ancestor’s U.S. federal and state census records. Multi-generational extended

family households were much more common in the 19th and early 20th

centuries than they are today. Well into your ancestor’s married life, you may

find one of her unmarried siblings or one of her widowed parents living in her

household. Lastly, a couple of unexpected, but reliable sources for a woman’s

maiden name include her social security application and her husband’s veteran

pension file (if he served in the U.S. military and predeceased her). Further

guidance: immigration records , census records , social security applications , veterans’ pension files .

It is important to note

that there are exceptions to this name change pattern. For example, in Spanish-speaking

countries, Portuguese-speaking countries, Italy, France, the Netherlands, and

Belgium, among others, women have traditionally retained their maiden names

throughout their lives, at least in official documents, and, in many cases,

also colloquially. In the historical regions of Galicia (straddling modern

Poland and the Ukraine), and Bohemia and Moravia (modern Czech Republic), only

the eldest son of a Jewish family was permitted to have a civil marriage and to

pass on his surname to his children; these laws effectively forced many younger

sons to have only a religious marriage and to register their children under

their wife’s maiden name.

Women’s lives are often

erased from the historical record. Women’s History Month is, in part, a

corrective measure to this regrettable trend. Through all of the variations

discussed above, the librarians at the Genealogy Center are dedicated to

helping you discover more about your female ancestors and their families.

Please visit us in person or online to learn more.