Yiddish Wall Newspapers

“Wall newspapers”—large, hand-lettered or typed newsletters posted in a shared communal space—have their roots in Soviet propaganda. Among the rich historical resources available through the Center for Jewish History’s digital collections are wall newspapers that form a portion of YIVO’s Displaced Persons Camps and Centers Poster Collection, RG 294.6. Created in the aftermath of World War II, these fragile documents provide a vivid glimpse into Jewish life in the DP camps. Friends of YIVO groups and other individuals collected these unique materials in order to preserve this history.1

In addition to the DP camp experience, these wall newspapers provide insights into the ongoing influence of the rich Soviet Jewish culture that had developed since the days of the Russian Civil War (1917-22) and was still operative in the camps.2 That Soviet Jewish culture should be so influential among the DP camp’s Jewish refugees might seem surprising, as most of them came from places that, at least until WWII, lay outside the Soviet Union. For example, in Italy, where many of the YIVO DP camp wall newspapers originate, refugees came from Poland, Romania, and other East European and Baltic countries.3 To make sense of the DP camp wall newspapers, it helps to look at their Soviet precursors.

The Model: Soviet Wall Newspapers

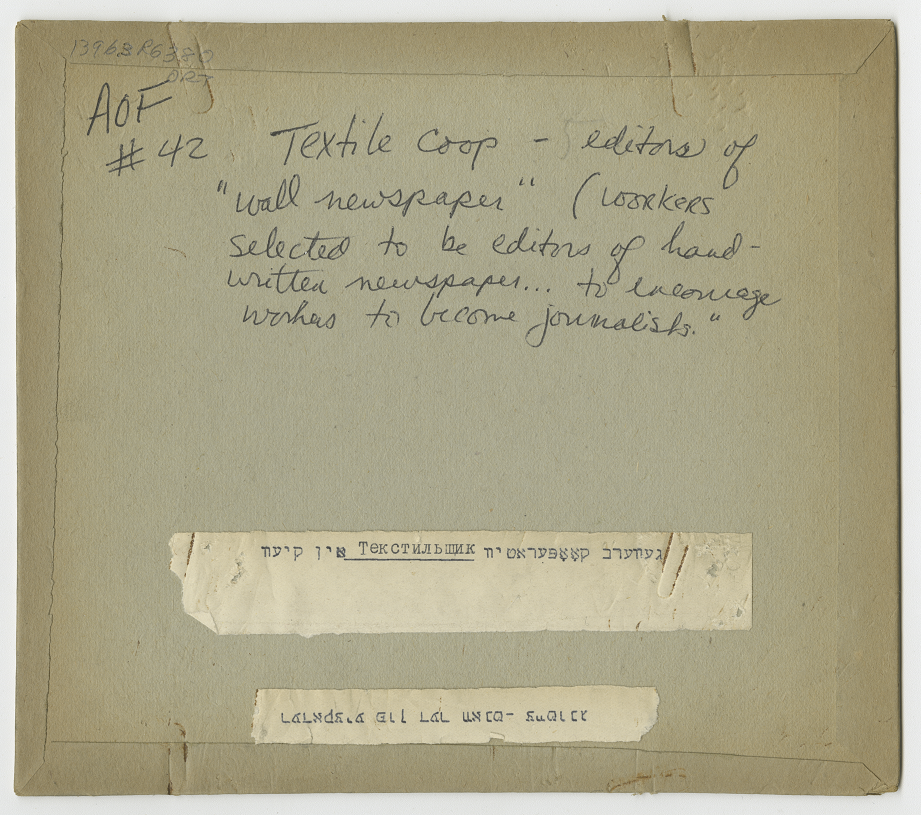

As this photograph (front and back) of the proud editors of an ORT textile cooperative’s wall newspaper attests,4 Soviet wall newspapers were more than just an expediency for lean times. They were organizing tools for any and every communal effort. In a 1901 essay Lenin remarked, “The newspaper is not only a collective propagandist and collective agitator, it is also a collective organizer.”5 By the time of the 13th Party Congress in 1924, the wall newspaper was officially embraced as a major tool for integrating “the masses” into the Marxist-Leninist social and political project.6

In conjunction with the widespread institutionalization of wall newspapers came the organization of the “worker-peasant correspondents’ movement”; that is, the factory workers, collective farmers, students, etc., who would create the wall newspapers for their community based on its members’ input.7 In the Soviet context, worker-peasant correspondents’ reports helped to police, as well as give voice to their communities.8 Every sort of Soviet community was organized by this powerful, if not always pleasant, combination of means. The ability of these correspondents and their humble papers to both create and shape community has led at least one scholar to suggest that far from “an inferior, ephemeral, and amateur part of the history of print,” they might more properly be considered “a central, communist contribution to the global long media history of user-generated content.”9

Soviet Yiddish Cultural Influence

Soviet Yiddish culture played a major role in the international Yiddish world. Kalman Weiser notes that the well-traveled Yiddish writer Dovid Bergelson, “in his 1926 essay ‘Three Centers,’ [. . .] argued that only in the progressive USSR did Yiddish literature and culture have opportunities for broader development.”10 This was no isolated feeling. According to Gennady Estraikh, “In the 1920s and 1930s, many ‘pure’ Yiddishists moved over to the Communist camp. [ . . . ] Soviet Communism’s international character and initial, unprecedented support of Yiddish culture convinced many people that the Soviet Union and pro-Soviet circles in other countries.11 But more than the refugees’ intimate familiarity with Soviet Jewish culture, these wall newspapers demonstrate the refugees’ repurposing of that framework in order to begin anew.

1947 Milan(?) DP Camp Wall Newspaper במעבר / B’Ma’avar (“in transit”)

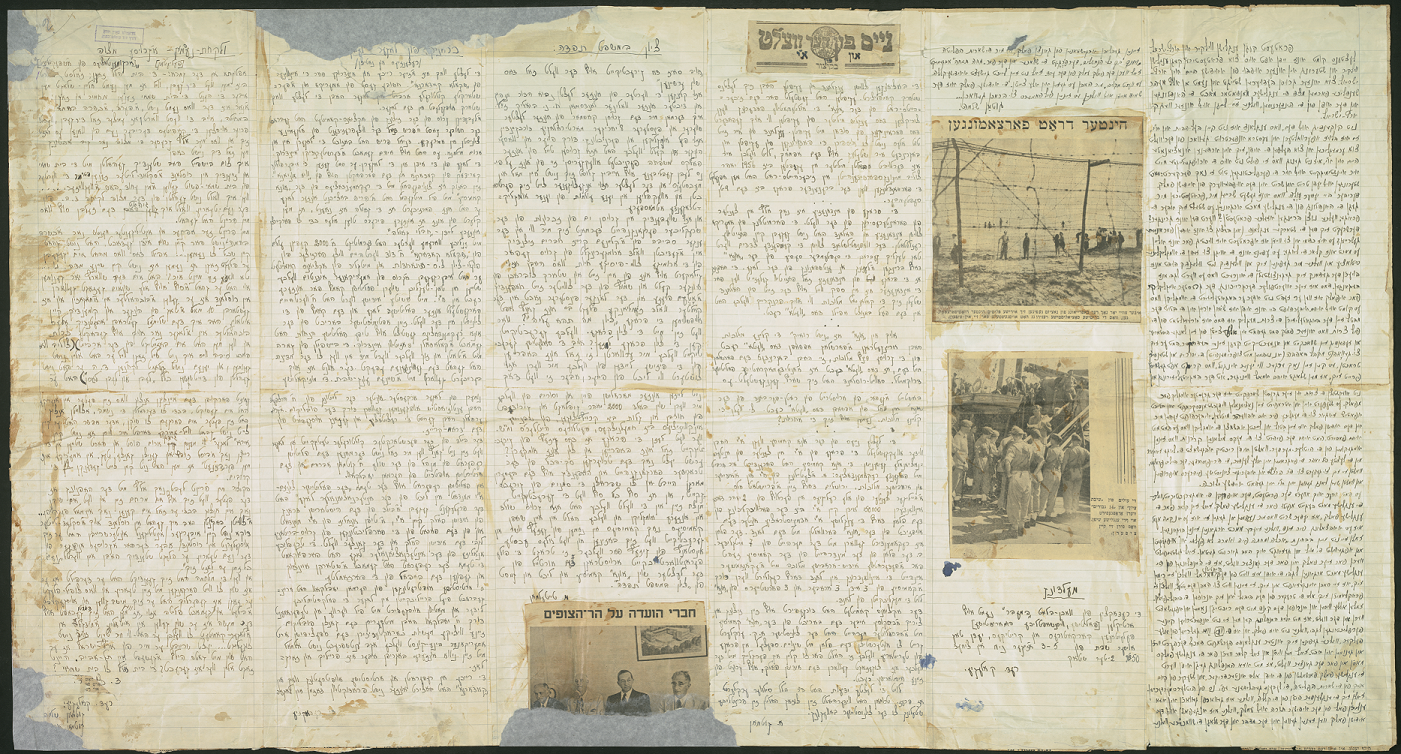

The Yiddish wall newspaper במעבר / B’Ma’avar (“in transit”) (see additional issues here, here, here, here, and here) provides an example of both the Soviet framework and its repurposing.12 Created in an Italian DP camp, probably in Milan, it was handwritten on strips of lined paper pasted onto printed newspaper from abroad. Photographs and drawings clipped from a variety of Yiddish publications illustrate each issue. A plea for camp residents to contribute articles, criticisms, and remarks concerning camp life, signed by the editorial board, appears towards the bottom of each issue. The editors, Abraham and Shlomo Gutman, themselves authors of most articles, provide an address that indicates that they, too, resided in the camp.

There is nothing resembling a nameplate; the paper’s name, B’Ma’avar, is buried in articles and notices that reference the paper as such. What is more, the issues are undated. Approximate dates can be deduced: the six issues held by YIVO date from ca. late July/early August 1947 (ITA.322) through 9 November (ITA 326) of the same year. While issues may be missing, this frequency—once or twice a month—is typical for wall newspapers which, as here, are unique items handmade by members of the community for which they were created.13 The inexpensive and recycled materials that went into this paper surely reflect camp conditions. They are also typical of wall newspapers since their inception during the Russian Civil War: paper shortages helped inspire the wall newspaper as a format, and such shortages remained a chronic problem for the Soviet publishing industry.14 Abraham and Shlomo Gutman, evidently familiar with the potential of the wall newspaper medium, created one to help and guide, as well as inform, their DP community.

At the same time, the Gutmans’ wall newspaper rejects Soviet objectives, including Soviet efforts to eliminate Jewish religious practice, abolish Zionism, and eliminate modern Hebrew from the USSR—even in the orthography of Yiddish words of Hebrew derivation. An issue of B’Ma’avar from mid-September 1947 demonstrates the reversal of Soviet priorities: it leads with an article about Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, holidays then taking place; it includes multiple references to emigration to Israel; the paper’s name is Hebrew and, next to a map of Israel clipped from a Yiddish newspaper appears the slogan, in Hebrew, “the land of Israel for the people of Israel!” The Zionist goals that underpin this, and all issues of B’Ma’avar, would have been shared by many in the Barletta camp; DP camps throughout Italy were filled with refugees seeking emigration to Palestine.15

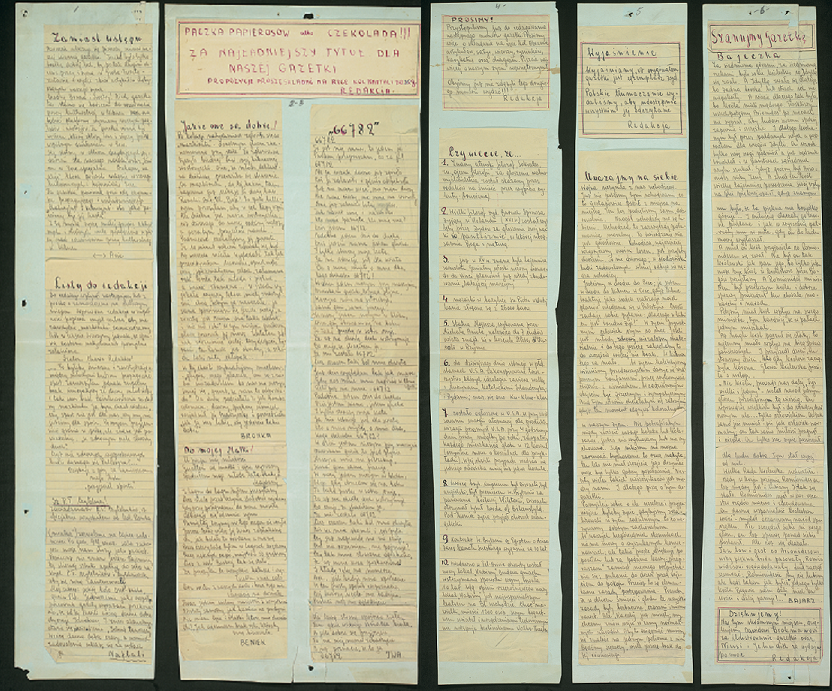

Polish Edition of a Yiddish Wall Newspaper, DP Camp Barletta (undated)

Like B’Ma’avar, most DP camp wall newspapers display great interest in user-generated content but little interest in layout, lettering, or graphic design. One that aimed somewhat higher was created in Camp Barletta, in southeastern Italy.16 YIVO only holds one issue. Although written in Polish, a notice informs the reader that the original version was in Yiddish; this translation was made to ensure accessibility to everyone. Where a nameplate might be expected there is a notice, in purple ink, of a competition “for the most beautiful title for our magazine,” with prizes of chocolate or cigarettes. The columns of text are given prominent headings and pasted onto strips of blue-green paper. While there are no illustrations, a call for caricatures suggests that the next issue might include imagery. Whether a second issue appeared, however, is unknown.

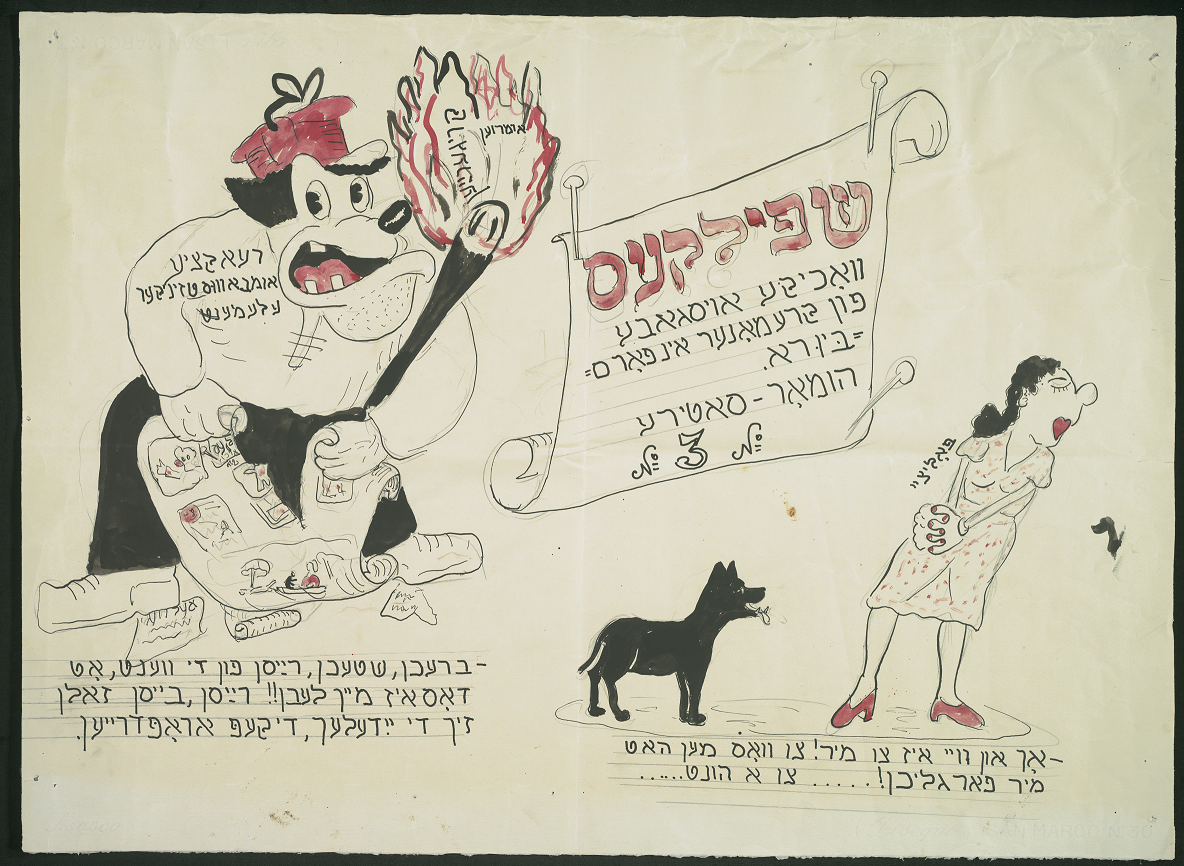

In the Soviet Union, pamphlets on creating your own wall newspaper provided meticulous guidelines for both ensuring Communist Party approval and fostering communal participation. A naming competition such as that held by the Camp Barletta wall newspaper was one technique recommended for enhancing engagement.17 Soviet-style wall newspapers were as significant in Soviet Yiddish communities as in any other Soviet linguistic community. “Shul un bukh,” a publishing house that coordinated Yiddish publishing throughout the Soviet Union, founded by Emes’s editor, Moyshe Litvakov, produced its own, Yiddish, versions of wall newspaper manuals.18 One such emphasized that “not less than 10 per cent of the paper should be taken up by pictures and another 10 per cent by the humour section.”19 In short, a premium was placed on visual entertainment. While B’Ma’avar and the Camp Barletta wall newspapers may have been limited in this respect, the children in the Cremona DP camp devoted their charming wall newspaper, שפּילקעס / Shpilkes (Pins), entirely to cartoons and caricatures.20

Conservation

We are fortunate that many issues of Shpilkes, as well as B’Ma’avar and other DP camp wall newspapers, not only survive in YIVO’s collections but also, thanks to funds provided by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims against Germany, have been digitized for public access. The fragility of wall newspapers has been regretted at least since 1925, when A. Lobovskii wrote that “wall newspapers are very difficult to preserve. Almost always, after being taken down after a certain amount of time, they are destroyed.”21 Jennifer Sainato, Preservation Services Manager for the Center for Jewish History, notes that “wall newspapers are a perfect example of a term often used in the field of Preservation/Conservation: inherent vice. Inherent vice is the tendency of material to deteriorate due to its own intrinsic characteristics.” The multiple layers of acidic paper from which these wall newspapers have been created, held together with glue that is itself acidic and shrinks with age, would not survive well in the best of circumstances. Their original use, hanging on a more or less exposed wall or bulletin board, has sped up their deterioration. While Jennifer has stabilized and mended tears and losses on YIVO’s wall newspapers, she tells us that “the embrittlement and discoloration cannot be reversed or stopped. . .The only solution is to digitally capture the collection and then close the originals to research, allowing the papers to embrace the sweet release of oblivion.”

Wall Newspapers from Birobidzhan

Currently, the Edward Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections project is engaged in preserving and digitizing the entirety of YIVO’s surviving prewar library and archival collections. These include newly preserved and documented wall newspapers (nos. 12-81 and 83-92) created as supplements to the Yiddish newspaper, Birobidzhaner Shtern. 22 They date to 1933, a key moment in the history of Birobidzhan.23 Designated a Jewish homeland in 1928, this territory in the Soviet Far East would be declared a Jewish Autonomous Region, with Yiddish its official language, in 1934, when it reached its brief peak as a Jewish land (1934-36).24 A large-format camera allowed the Center for Jewish History’s Senior Photographer, Gloria Machnowski, to digitize these oversized materials with a minimum resolution of 400dpi; partial images have been stitched together using photoshop in post-production.

Founded October 30, 1930, the Birobidzhaner Shtern had quickly gained popularity.25 On October 3, 1932, its new editor, Henekh Kazakevich, recently arrived from Kharkiv (where he had served as editor of Royte Velt),26 along with his friend, the writer Dovid Bergelson, 27 visiting from Berlin, would join in celebrating the newspaper’s hundredth issue.28 We eagerly anticipate the opportunity to view the paper’s little-studied wall newspaper supplements, which would appear to have been created on Kazakevich’s initiative and, according to Nikolai Borodulin, contain “more critical materials than the official Birobidzhaner Shtern.29 They represent both an important moment in Soviet Jewish culture and a medium, the wall newspaper, that would find traction far beyond the borders of the Soviet Union.

Jeanne-Marie Musto, Independent Scholar

Notes

- On the collection of the DP Camp collections see: “The YIVO Institute and the YIVO Archives: A Brief History,” in Guide to the YIVO Archives, compiled and edited by Fruma Mohrer and Marek Web (New York: YIVO Institute for Jewish Research; Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1998), pp. xi – xix; here, p. xviii. Full text available through the Center for Jewish History online catalog: http://search.cjh.org/permalink/f/d40h2n/cjh_digitool431423.

- “Yiddish wall newspapers began to function in the mid-1920s. During the Civil War wall newspapers intended for a Jewish readership were written in Russian, as the Bolsheviks had neither time nor cadres to produce Yiddish materials.” Anna Shternshis, “From the Eradication of Illiteracy to Workers’ Correspondents: Yiddish-language mass movements in the Soviet Union,” East European Jewish Affairs, vol. 32:1 (2002), p. 130. YIVO Library Periodicals Collection, call no. 015009229(A); permalink to Center for Jewish History online catalog record: http://search.cjh.org/permalink/f/11esd5n/CJH_ALEPH000389739.

- Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, “Jewish Displaced Persons in Postwar Italy, 1945-1951,” unpaginated, section “Survey among Refugees,” 3rd paragraph, https://jcpa.org/article/jewish-displaced-persons-in-postwar-italy-1945-1951/.

- YIVO Archives, ORT Photograph Collection, RG 380, Series IV: Personalities, undated, folder 1396: Students and graduates of evening adult course at ORT textile cooperative, Kiev, ca. 1925, photograph 3. Permalink to Center for Jewish History online catalog record: http://search.cjh.org/permalink/f/d40h2n/CJH_ALEPH005541138. On ORT see YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/ORT.

- Peter Kenez, The Birth of the Propaganda State: Soviet Methods of Mass Mobilization, 1917-1929 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1985), p. 233.

- Kenez, pp. 237-38.

- Kenez, p. 233-37.

- Kenez, p. 237.

- Birgitte Beck Pristed, “Soviet Wall Newspapers: Social(ist) Media of an Analog Age,” in The Oxford Handbook of Communist Visual Cultures, ed. Aga Skrodzka, Xiaoning Lu, and Katarzyna Marciniak (Oxford University Press: Online Publication Date: Aug 2019), DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190885533.013.5. No page numbers; here: 2nd paragraph of introduction.

- Kalman Weiser, “The Capital of ‘Yiddishland’?,” ch. 12 in Warsaw: The Jewish Metropolis: Essays in Honor of the 75th Birthday of Professor Antony Polonsky, ed. Glenn Dynner and François Guesnet (Boston: Brill, 2015), p. 303. YIVO Library call no. 000134124; permalink to Center for Jewish History online catalog record: http://search.cjh.org/permalink/f/d40h2n/CJH_ALEPH004612812. Weiser cites Dovid Bergelson, “Drey tsentren,” אין שפאן / In Shpan 1 (April 1926): 84-96. YIVO Bund Periodicals Collection, call no. 500000000, and other YIVO collections; permalink to Center for Jewish History online catalog record: http://search.cjh.org/permalink/f/d40h2n/CJH_ALEPH000041535.

- Gennady Estraikh, “The Kultur-Lige in Warsaw: A Stopover in the Yiddishists’ Journey between Kiev and Paris,” ch. 13 in Warsaw: The Jewish Metropolis: Essays in Honor of the 75th Birthday of Professor Antony Polonsky, ed. Glenn Dynner and François Guesnet (Boston: Brill, 2015), p. 341. YIVO Library call no. 000134124; permalink to the Center for Jewish History online catalog record: http://search.cjh.org/permalink/f/d40h2n/CJH_ALEPH004612812.

- YIVO Archives, RG 294.6, Series II: Italy, 1946-1948, undated. Subseries 8: Miscellaneous materials, circa 1947, undated. Folder 23, items ITA.321 through ITA.326; permalink to Center for Jewish History online catalog record: http://search.cjh.org/permalink/f/11esd5n/CJH_ALEPH000389739. The rectangular blue stamp on each issue denotes that these items were among the extensive Italian DP camp materials collected by the Central Committee of the Organization of Jewish Refugees and transferred to YIVO via David Kupferberg. Guide to the YIVO Archives, pp. 66-67. Full text available through the Center for Jewish History online catalog: http://search.cjh.org/permalink/f/d40h2n/cjh_digitool431423.

- Pristed, “Soviet Wall Newspapers” (no page numbers); here: section entitled “The Material: A Low-Tech, Hybrid, Mobile, and Destructible Medium,” 4th paragraph.

- David Shneer, Yiddish and the Creation of Soviet Jewish Culture, 1918-1930 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 100. Shneer’s work is held at YIVO, call no. 000111948; permalink to Center for Jewish History online catalog record: http://search.cjh.org/permalink/f/d40h2n/CJH_ALEPH000037837

- On DP camps in Italy see: Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, “Jewish Displaced Persons in Postwar Italy, 1945-1951,” https://jcpa.org/article/jewish-displaced-persons-in-postwar-italy-1945-1951/.

- YIVO Archives, RG 294.6, Series II: Italy, 1946-1948, undated. Subseries 5: Displaced Persons Camps and Centers, 1946-1948, undated. Subseries B: Camp Barletta, 1946-48, undated. Folder 7, ITA.86. Permalink to the Center for Jewish History online catalog record for YIVO Archives’ Displaced Persons Camps and Centers Poster Collection, RG 294.6: http://search.cjh.org/permalink/f/d40h2n/CJH_ALEPH004600686.

- Kenez, pp. 3-4.

- David Shneer, pp. 103 and 131; on Litvakov, see also Gennady Estraikh, “Litvakov, Moyshe,” in the YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Litvakov_Moyshe.

- Anna Shternshis, “From the Eradication of Illiteracy to Workers’ Correspondents: Yiddish-language mass movements in the Soviet Union,” East European Jewish Affairs, vol. 32:1 (2002), p. 130. YIVO Library Periodicals Collection, call no. 015009229(A); permalink to Center for Jewish History online catalog record: http://search.cjh.org/permalink/f/11esd5n/CJH_ALEPH000389739. Shternshis cites Maḳs Ayznshṭaṭ, Der arbeṭer-ḳlub: organizatsye un meṭodiḳ (Mosḳṿe: Farlag “Shul un bukh”, 1926), pp. 81-84. Ayznshṭaṭ’s Arbeṭer-ḳlub is held at YIVO, call no. 000059204; permalink to Center for Jewish History online catalog record: http://search.cjh.org/permalink/f/d40h2n/CJH_ALEPH000298175

- YIVO Archives, RG 294.6, Series II: Italy; Subseries 5: Displaced Persons Camps and Centers, 1946-1948, undated; Subsubseries D: Camp Cremona, 1946-1948, undated, Folder 12, Item ITA.158, שפּילקעס / Shpilkes (Pins) #3 Part 1. Permalink to the Center for Jewish History online catalog record for YIVO Archives’ Displaced Persons Camps and Centers Poster Collection, RG 294.6: http://search.cjh.org/permalink/f/d40h2n/CJH_ALEPH004600686.

- Pristed, “Soviet Wall Newspapers” (no page numbers), section entitled “The Material: A Low-Tech, Hybrid, Mobile, and Destructible Medium,” 3rd paragraph, and n. 47, citing A. Lobovskii, Stennaia gazeta, Biblioteka raboche-krest’ianskoi molodezhi (Moscow: Novaia Moskva, 1925), p. 72.

- YIVO Archives RG-30, May Cohn Russia and Soviet Union (Vilna Archives) Collection, 1837-1940, Series 3: Oversized, undated, 1908-1930s, Box 7/4:6 and 7/4:7. Permalink to Center for Jewish History online catalog record: http://search.cjh.org/permalink/f/d40h2n/CJH_ALEPH000133715.

- On YIVO’s Birobidzhan-related materials, including these wall newspapers, see Nikolai Borodulin, ”A Unique Birobidzhan Collection,” East European Jewish Affairs, vol. 30:2 (2000): p. 119. YIVO Library Periodicals Collection, call no. 015009229(A); permalink to Center for Jewish History online catalog record: http://search.cjh.org/permalink/f/11esd5n/CJH_ALEPH000389739.

- See David Shneer, 2010, “Birobidzhan,” YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Birobidzhan.

- On the Birobidshaner Shtern see Boris Kotlerman, 2010, “Birobidzhaner Shtern,” YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Birobidzhaner_Shtern.

- See YIVO Encyclopedia https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Royte_Velt_Di.

- See YIVO Encyclopedia https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Bergelson_Dovid.

- Gennady Estraikh, “Arcadian Dreams of David Bergelson and His Berlin Circle,” Studia Rosenthaliana, vol. 41, Between Two Words: Yiddish-German Encounters (2009), p. 168; Gennady Estraikh, In Harness: Yiddish Writers’ Romance with Communism (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 2005), p. 168. YIVO Library call no. 000127695; permalink to Center for Jewish History online catalog record: http://search.cjh.org/permalink/f/d40h2n/CJH_ALEPH000378915.

- Nikolai Borodulin, ”A Unique Birobidzhan Collection,” East European Jewish Affairs, vol. 30:2 (2000): p. 119. YIVO Library Periodicals Collection, call no. 015009229(A); permalink to Center for Jewish History online catalog record: http://search.cjh.org/permalink/f/11esd5n/CJH_ALEPH000389739.