By Lauren Gilbert, Director of Public Services, Center for Jewish History

“Yours very respectaly, M. Blum”: Correspondence between a New Jersey Jewish Farmer and the Industrial Removal Office, 1902-1905

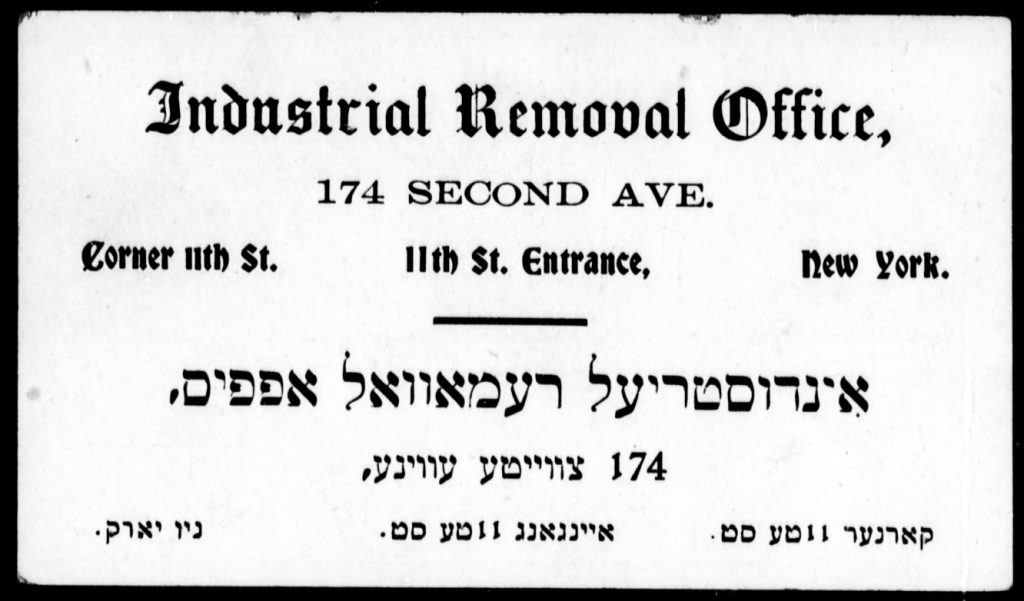

In response to the massive waves of Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe around the turn of the 20th century, leaders of the German-Jewish community in New York City founded the rather forbiddingly named Industrial Removal Office (IRO) to relocate new arrivals from teeming cities on the East Coast to Jewish communities in smaller cities and towns. Hoping to meet the industrial demands of an expanding nation, the IRO would secure jobs and arrange for room, board, and transportation. A largely philanthropic effort to relieve poverty, unhygienic conditions, and overcrowding in urban slums, the IRO also represented an attempt by these Americanized social reformers to encourage assimilation and prevent an antisemitic backlash against the new immigrants that threatened to jeopardize their own hard-won social standing.

The relocated immigrants, or “removals,” often corresponded with IRO headquarters, as did their employers, the IRO field officers, and local community members. Many of these letters are preserved in the Records of the Industrial Removal Office held by the American Jewish Historical Society (AJHS). These conversations among Jews of various classes and backgrounds, not meant for public consumption, represent the voices of ordinary people expressing their praise and thanks, and occasionally their frustrations, fears, prejudices, or distrust of their new neighbors, employers, or staff.

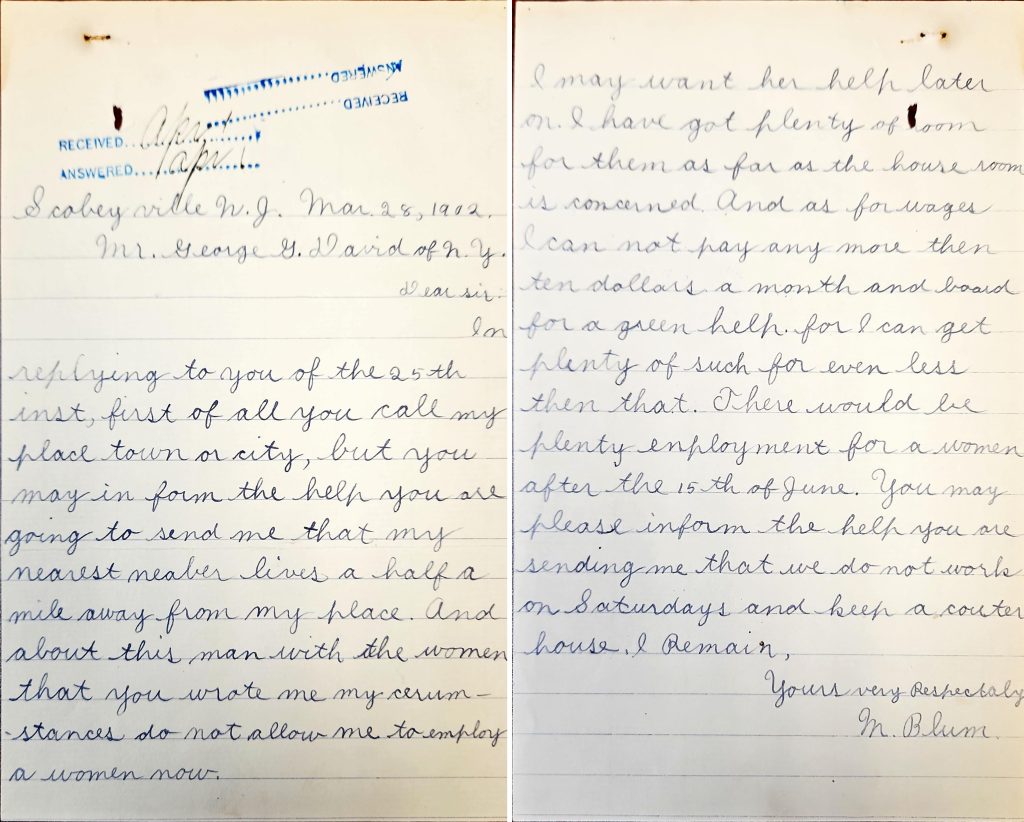

Just one correspondent among thousands, M. Blum, a Jewish farmer in Scobeyville, NJ, near the Jersey Shore, communicated with the New York IRO office in the spring of 1902. On March 25, the IRO reached out to Blum to acknowledge his request for a farmhand, and to inform him that they had a man who was willing to “come to your town,” provided that he could bring his wife along. In Yiddish-inflected, error-prone English, Blum chides his correspondent George David of the IRO for referring to his locale as a town (“first of all, you call my place town or city, but you may inform the help you are going to send me that my nearest neaber lives a half a mile away from my place”) and refusing the offer of a man and his wife (“my circumstances do not allow me to employ a women now”). He further requests: “You may please inform the help you are sending me that we do not work on Saturdays and keep a couter [kosher] house.” (See below–all quotes are taken verbatim from the letters.)

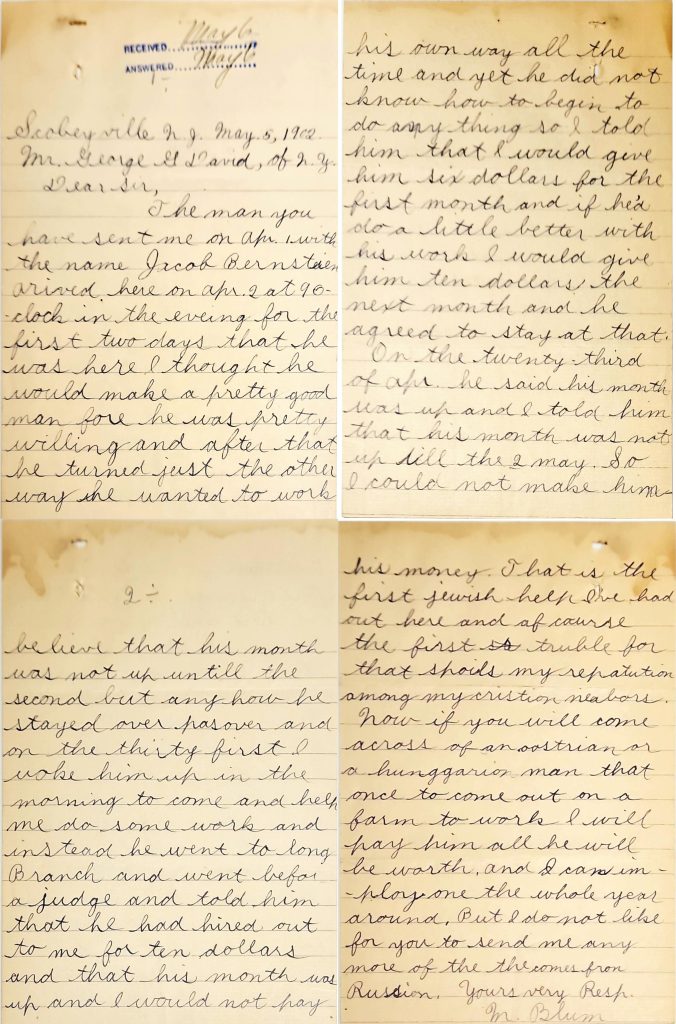

On May 5, Blum again writes to George David at the IRO, complaining about the help he had been sent. He describes a conflict over wages, grumbles that the man went before a judge claiming he was not given what he was owed, and frets that this “first Jewish help I have had here” will spoil “my repatution among my Cristion neabors.” Blum concludes with a very specific request for the man’s replacement: “Now if you will come across an Austrian or a Hungarrian man that once [wants] to come out on a farm to work I will pay him all he will be worth, and I can imploy one the whole year around. But I do not like for you to send me any more of the the comes from Russian.” (see below)

A small-town Jewish farmer (presumably of Austro-Hungarian origin), Blum was subject to the usual petty, internecine prejudices expressed by the various Jewish communities. Though he was no wealthy, privileged German Jew, Blum felt resentful and uncomfortable with the new Russian arrivals, and clearly felt it was safe to air these sentiments within the confines of a Jewish organization. Like the Jewish grandees, he was concerned about how individual Jews were perceived by the outside world (“my Cristion neabors”), and how that would reflect personally on him and on the Jewish community at large.

The IRO response, dated the following day, pointedly ignores Blum’s request for “an Austrian or a Hungarrian man,” simply asking him to clarify how much he is willing to pay, as “no man will go out without knowing this.”

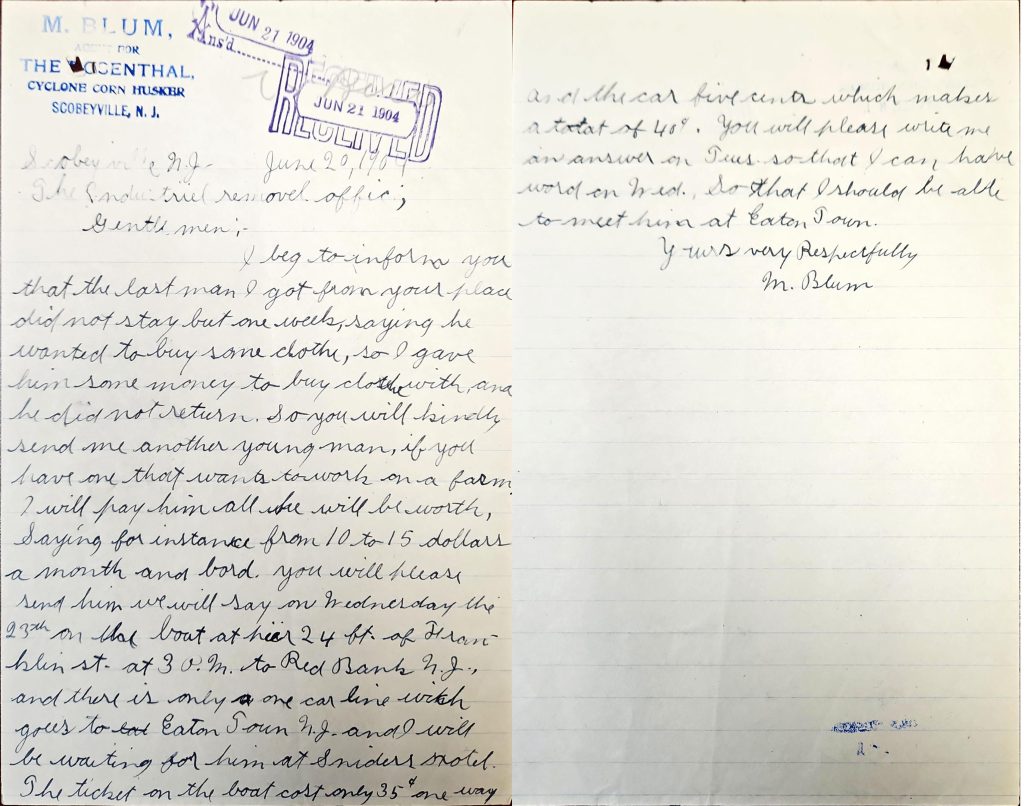

Two years later, on June 21, 1904, Blum once again writes to IRO headquarters, this time on stationery pronouncing him as an agent for “The Rosenthal Cyclone Corn Husker.” Blum once more complains about help that was sent to him by the IRO: “I beg to inform you that the last man I got from your place did not stay but one week, saying he wants to buy some clothe, so I gave him some money to buy clothe with, and he did not return.” He follows up with a request: “you will kindly send me another young man, if you have one that wants to work on a farm,” followed by detailed travel instructions via Red Bank and Eatontown. (below)

The following year, on March 15, 1905, Blum reaches out again to the IRO to request two farmhands “that know how to cut wood and handle horses if possable.” In reply, IRO Assistant Manager “A.J.B” asks Blum if he would “guarantee that these men will be employed all year” and requests references from “people of standing,” as “we take a personal interest in our beneficiaries” and “you are a stranger to us.”

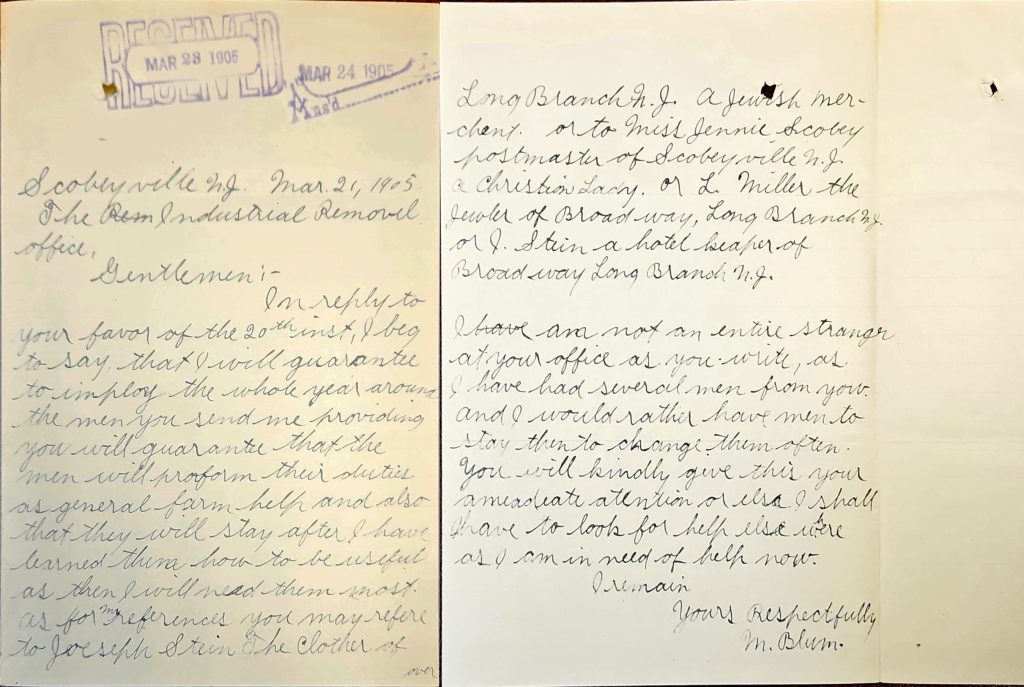

In a series of increasingly snippy exchanges, the relationship between Blum and the IRO deteriorates further. Blum responds that he will “guarantee to imploy the whole year around the men you send me providing you will guarantee that the men will perform their duties as general farm help and also that they will stay after I have learned them how to be useful as then I will need them most.” He supplies the requested references, including three Long Branch merchants as well as “Miss Jennie Scobey postmaster of Scobeyville a Christion Lady,” and reminds the IRO: “I am not an entire stranger at your office as you write, as I have had several men from you and I would rather have men to stay then to change them often.” (below)

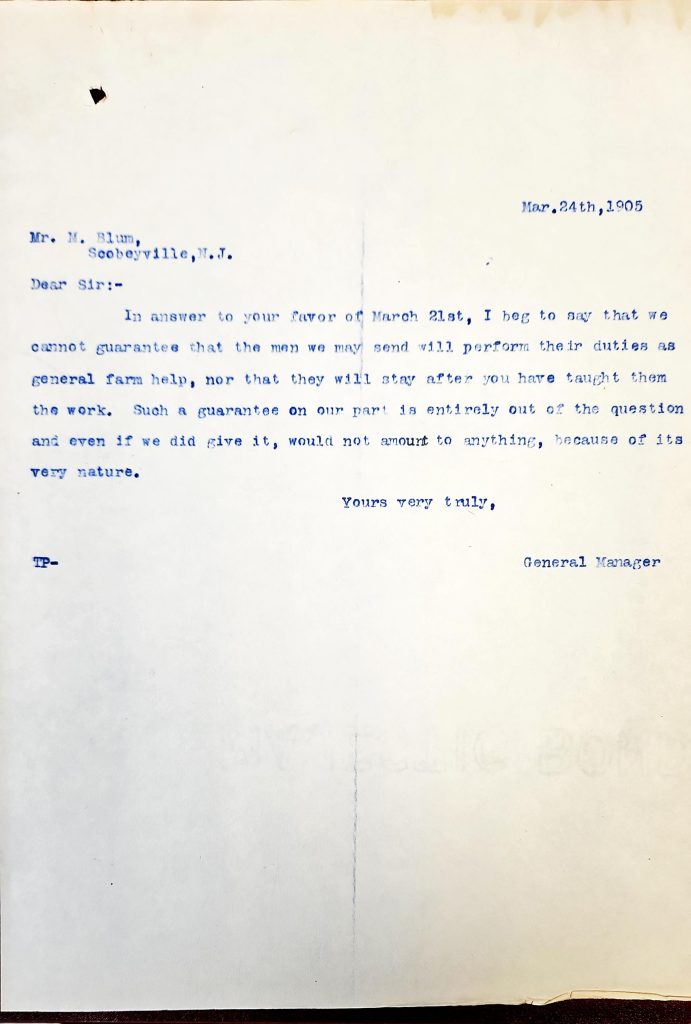

IRO General Manager “TP” responds on March 24 that “we cannot guarantee that the men we may send will perform their duties as general farm help, nor that they will stay after you have taught them the work. Such a guarantee is entirely out of the question, and even if we did give it, would not amount to anything, because of its very nature.” (below)

In a response dated March 27, Blum reiterates that he “could not give the required guarantee” (to employ the men all year) “unless the men will prove useful to me” and asks once again “whether you will send anybody or not.”

The IRO responds with a terse missive on March 28 in which they simply ask Blum to “kindly refer us to some persons of standing in this city or in your neighborhood,” which he had in fact already done on March 21. One assumes that the partnership between M. Blum and the Industrial Removal Office ends there, as does the correspondence in the “Scobeyville” folder.

If the tone of the letters is any indication, M. Blum might not have been the most even-tempered employer. In any case, small-town America was never much of a draw for the new Jewish immigrant, who felt more at home in an urban enclave with a large Jewish population and easy access to synagogues, kosher butchers, Yiddish theaters, and social organizations. Many of the “removals” eventually returned to the city to be near friends and family. Even Scobeyville, NY, just 50 miles from New York City, much closer than most of the “removal” destinations, could feel alien to a new arrival.

Lauren,

I always learn something new when I read your blog

Thank you

Enid

This is an interesting glimpse of a Jewish life removed from urbanity . It must have been hard to assimilate in this alien landscape. I give Mr. Blum credit for this, although he doesn’t appear to be the easiest of bosses!