Dramatis personae: Addressing a playwright

Out of the Archives

How to Find Arthur Miller Without Even Trying, or, The Perks of Being the First Lady

by Stefanie Halpern, Archival Processing Fellow, Center for Jewish History

I was processing a collection on the Friends of Ida Kaminska Theatre, a foundation that existed for only a few years to raise funds and to book shows for Kaminska, the much-loved (and Academy Award-nominated) Polish-Jewish actress. In the process of processing, I came across a letter that mentioned Arthur Miller.

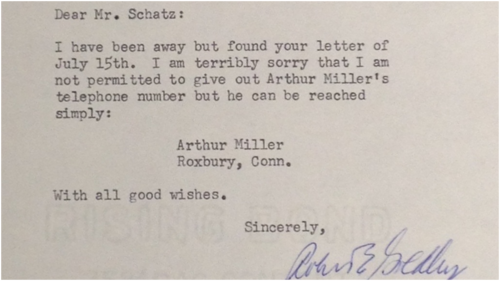

More specifically, the sender of the letter (Rabbi Robert E. Goldburg) was providing the recipient (Julius Schatz, the secretary of the foundation) with Miller’s address. Here are Rabbi Goldburg’s words: “I am terribly sorry I am not permitted to give out Arthur Miller’s telephone number but he can be reached simply: Arthur Miller, Roxbury, Conn.” At first I was intrigued. (No address? No zip code?) Then I was jealous. That Arthur Miller really had it good—he was so famous that he was his address.

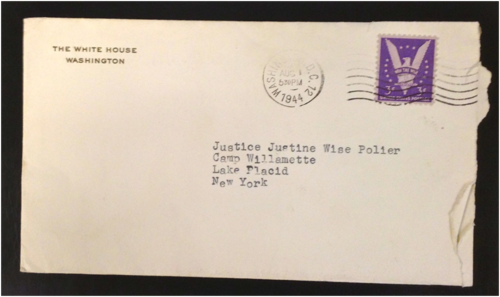

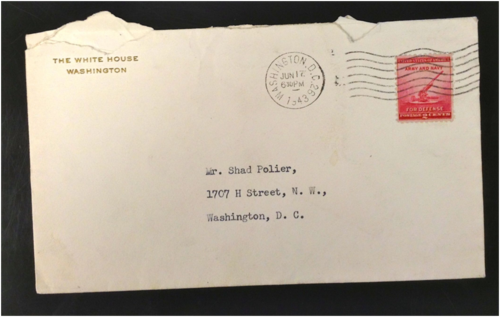

I worked on a second collection that contained correspondence between Eleanor Roosevelt and Judge Justine Wise Polier. Polier was the first female judge in New York, appointed by Mayor Fiorella LaGuardia in 1935. Besides being generally excited that I had touched Eleanor Roosevelt’s hands (using the transitive properties by which my hand + letter and Eleanor Roosevelt’s hand + letter = my hand + the First Lady’s hand), I found a few other postal-related treats in this collection.

The envelopes Eleanor Roosevelt sent from the White House include war propaganda stamps released from 1940-42, featuring pictures of the Statue of Liberty, an anti-aircraft gun and an uplifted torch. The last stamp, released on July 4, 1942, is adorned with an eagle in the shape of a V for victory and the text “Win the War.”

After she left the White House, Roosevelt didn’t even need to put a postage stamp on any of the letters she sent. Instead, using an ink stamp of her own signature, she just “franked” them herself.

About the Archival Fellowship program:

The Center for Jewish History’s newly launched Archival Fellowship Program provides young scholars in the field of Jewish Studies with the opportunity to gain hands-on experience in an archival institution, using the knowledge of language, history and culture they have developed in their studies. By working with diverse collections from our partner institutions, fellows are introduced to basic archival theory and practice, strengthening their capabilities as researchers and opening up new professional directions for them.

The primary focus of the fellowship is on archival processing. In the course of processing a collection from start to finish, the fellows organize the collection in ways that will make the materials more accessible to researchers; write a descriptive online guide (also known as a finding aid) so that potential users can determine whether the material is relevant to their interests; and rehouse the collection to ensure its long-term stability.

In the Winter 2014 pilot of the program, our Center archivists trained two fellows, Stefanie Halpern (author of this post) and Catherine Greer, who boast subject specialties in Jewish Studies and the performing arts. The pilot set us on a steady course for a larger-scale iteration of the program in the summer of 2014, when we will host six international and domestic fellows with support from The Rothschild Foundation (Hanadiv) Europe. For more information about this and other Center fellowships, see our list of fellowship programs or contact our Senior Manager for Archival Services, Rachel C. Miller, at rcmiller@cjh.org.