By Lauren Gilbert

Director of Public Services, Center for Jewish History

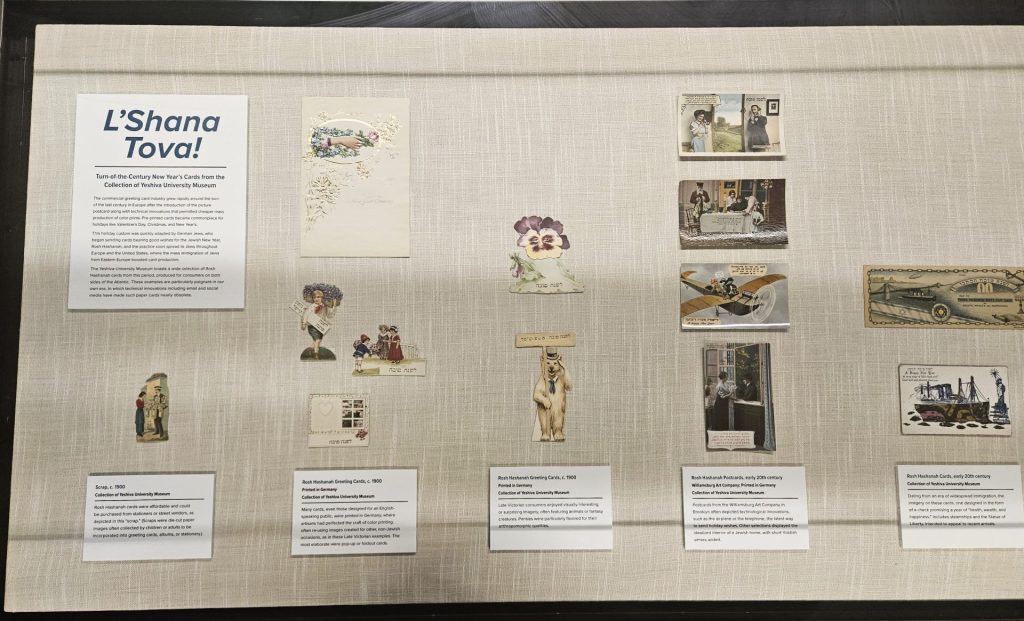

L’Shana Tova! Turn-of-the-Century New Year’s Cards from the Collection of Yeshiva University Museum

The commercial greeting card industry grew rapidly around the turn of the last century in Europe after the introduction of the picture postcard along with technical innovations that permitted cheaper mass production of color prints. Pre-printed cards became commonplace for holidays like Valentine’s Day, Christmas, and New Year’s.

This holiday custom was quickly adapted by German Jews, who began sending cards bearing good wishes for Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, and the practice soon spread to Jews throughout the continent and the United States, where the mass immigration of Jews from Eastern Europe boosted card production. The Yeshiva University Museum boasts a wide selection of Rosh Hashanah cards from this period, produced for consumers on both sides of the Atlantic.

The cards were affordable and could be purchased from stationers or street vendors, as depicted in this “scrap” [image 1] showing a woman examining a selection of Rosh Hashanah greetings. (Scraps were die-cut paper images often collected by children or adults and incorporated into greeting cards, albums, or stationery, much like the stickers of today.)

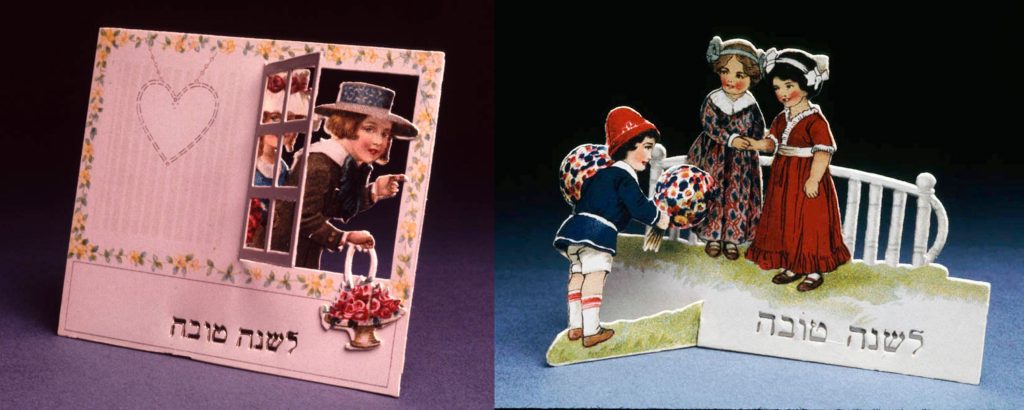

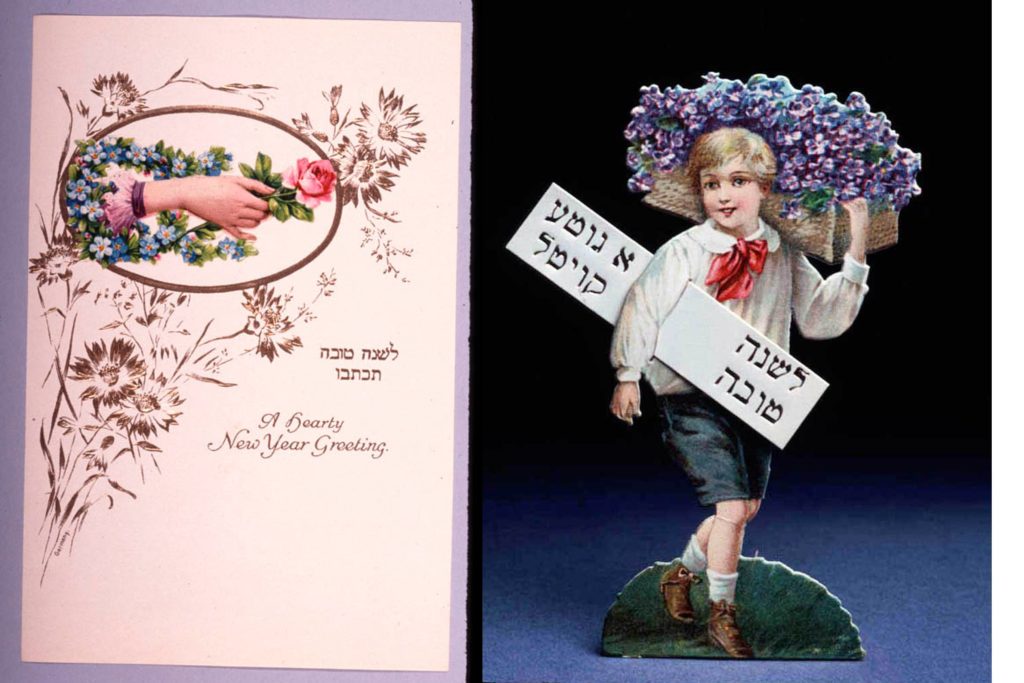

Many cards, even those designed for an English-speaking public, were printed in Germany, where artisans had perfected the craft of color printing, often re-using images created for other, non-Jewish occasions, as in these late Victorian examples [images 2-5]. The most elaborate were pop-up and foldout cards.

Late Victorian consumers enjoyed visually interesting or surprising imagery, often featuring animals [image 6] or fantasy creatures. Pansies were particularly favored for their anthropomorphic qualities [image 7].

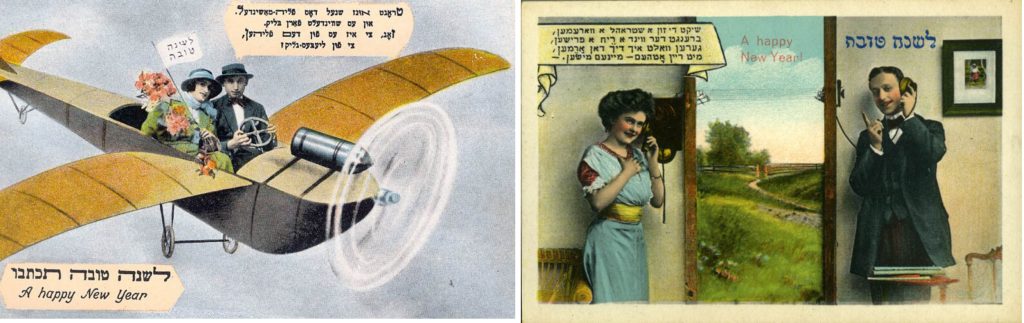

Early 20th century postcards from the Williamsburg Art Company in Brooklyn often depicted technological innovations, such as the airplane [image 8] or the telephone [image 9], the latest way to send holiday wishes.

Other postcards from the Williamsburg Art Company displayed the idealized interior of a Jewish home, with short Yiddish verses added [image 10]. In one card [image 11], a man can be seen passing a Rosh Hashanah greeting through a window. (How meta!)

The Hebrew Publishing Company in New York, a rival to the Williamsburg Art Company, was known for elaborate pop-up cards featuring synagogue interiors [image 13] or biblical scenes [image 14].

Dating from a decade of widespread immigration, a card titled “A Good Year Ship Ticket” [image 14] from the Hebrew Publishing Company was designed to appeal to recent or soon-to-be immigrants, depicting a train and a factory on either side of the Statue of Liberty and featuring the Hebrew text of the Traveler’s Prayer.

These examples are particularly poignant in our own era, in which technical innovations including email and social media have made such paper cards nearly obsolete.